Internal market and competition

Rémi Bourgeot

-

Available versions :

EN

Rémi Bourgeot

Introduction

Debate over the euro zone is always passionate and contradictory. However the antagonists who face each other just over austerity and its impact on the economy tend to ignore the source of the problem. The controversy over the errors made by Reinhart and Rogoff[1] illustrates this. Most comments are restricted to the dilemma of public debt and growth, disregarding the fact that the way the euro crisis is being managed in fact reflects a new economic regime which will have major repercussions long term - or rather it might mirror a classical economic regime that is strikingly similar to the economic adjustments that typified the gold standard.

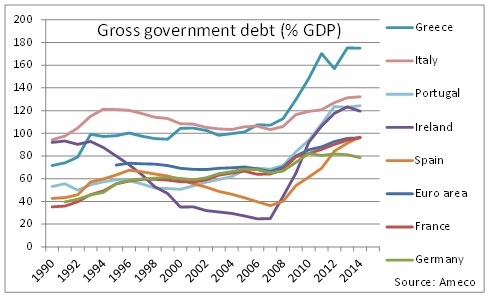

Although the euro crisis is seen as one of public debt the strategy to manage it has clearly not achieved its goals of reducing deficit and debt ratios. As increasing numbers of observers quite rightly stress, this policy did lead to economic contraction and even depression. This is all the more true since it has been implemented simultaneously in countries within the same economic zone[2]. This recessionary impact has automatically led to an increase in public debt in countries where for several decades the Welfare State has prevailed. Conjointly with soaring debt levels, GDP contraction has led to a massive rise in debt-to-GDP ratios, the sacrosanct gauge when we speak of a public debt crisis.

We might wonder at the series of errors made by some eminent specialists. Notably we should note that the traditional specialists in developed countries were barely accustomed to this kind of exercise, often focusing on short-term forecasting or on the contrary on a type of abstraction which does not always allow for the perception of earthly issues. It was noticeable moreover from the start of the crisis that those analysts who seemed to be more at ease with these concepts were experienced in emerging countries and their monetary crises, particularly Russia or the countries of South East Asia in the 1990's. These fundamental errors over the determinants of the economic situation are all the more surprising since the crisis management strategy via austerity is in fact coherent. However, this coherence comes into sight only on condition that the pattern is analysed according to a truly classical economic stance which is based on the belief in the more widespread application of the German trade surplus model. In particular, if the recessionary impact of austerity has been underestimated it is mainly because we are expecting a great deal (and too much) of a recovery in exports especially in the countries in crisis, for the recovery to gain momentum and last long term.

However the true economic model which austerity is linked to seems to be claimed at the cost of great discomfort by its own proponents. In particular the crisis management strategy is purportedly aimed at fighting against the euro zone's fragmentation whilst this phenomenon is only the financial partner to this violent balancing strategy of current accounts in each deficit country. Like the Germany of Agenda 2010 but in a much more brutal manner the countries in crisis have had to commit to a policy of demand contraction at large in order to recover a level of competitiveness that will enable them to grow through exports. Whilst the core of the euro zone already tends to have an excessive export bias it seems that Europe's stance towards the global crisis consists in applying a model widely which is in fact impossible to generalise. Indeed the success of this model is necessarily based on a strong external demand while, on the contrary, we find ourselves in a generalised climate of weak world demand, of which the "currency war" is but a symptom. In the face of this actual "demand war" we see the European Union at large, which as a matter of fact is the world's leading economy, forced to adopt the strategy of a small country.

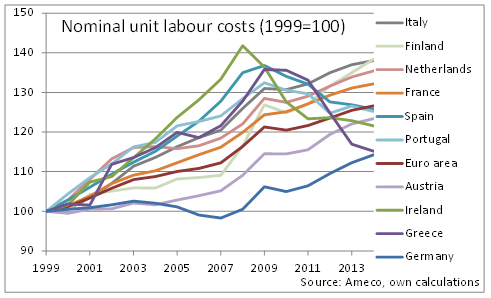

In this uncertain and unusual context a dominant narrative emerged which maintained that the countries in crisis "had lived beyond their means" in the widest sense of the term, and to be more precise that they had experienced a wage drift which was the cause of their deficits at large. The solution to the crisis was said to lie therefore in a broad correction of wages in these countries. Although common imbalances were the result of divergences in unit labour costs, there has not however been any wage drift. A detailed analysis shows that divergences in unit labour costs mainly come from divergence in inflation between the core and the periphery, sluggish productivity gains in most countries in crisis and pressure on wages in Germany. This issue is the focus of this study.

1. International adjustments which recall the gold standard

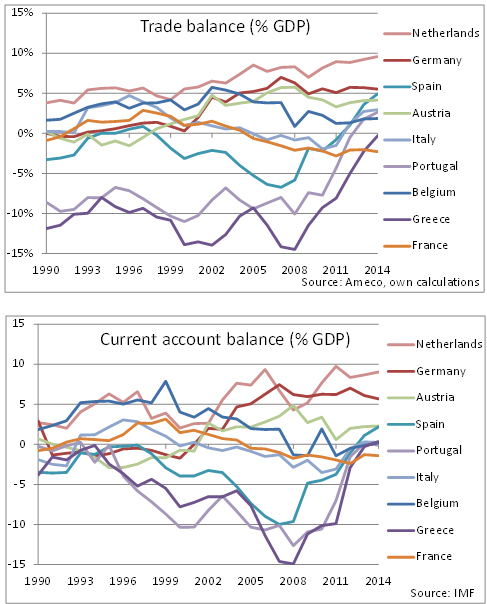

It is certain that the crisis in economic thinking has contributed to these mistakes. But beyond the gap towards declared goals, we should identify quite precisely the logic to which the policies that have been introduced correspond. Although it is clear that debt and growth dynamics are closely linked, there is one target that austerity policies and the contraction in demand generally never miss. Here we mean the current account balance[3], or more simply the trade balance. In this sense the adjustment framework that was established from the very first months of the euro crisis has not been dissimilar to the management of the gold standard.

The whirlwind clearance of current account deficits

Hence in all the so-called peripheral countries in the euro zone there has been a clear balancing in their external accounts. Greece, which had a trade deficit of over 10% of GDP in 2008, is fast reaching trade balance while in full recession. The Spanish balance is doing the same having started off at around 7%, Portugal at nearly 10%. Italy, a country with a strong productive base, which has not experienced Spain's credit bubble, has not seen such critical levels as far as its trade deficit is concerned but it is nearing balance. Hence, the line which really divides Europe is that between the countries in surplus and those in deficit - not from the fiscal balance point of view but from as far as the current account and the trade balance are concerned[4].

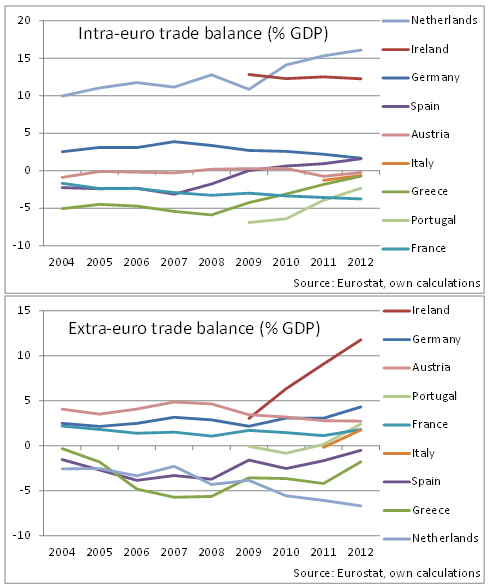

The surpluses in the countries in the north continue to grow, but we should note the specific situation in Germany whose surpluses continue to spread (from basic levels that were already high - over 5% of the GDP), especially vis-à-vis the rest of the world, whilst they are decreasing vis-à-vis the rest of the euro zone. The reorientation of the German trade surpluses towards the rest of the world echoes the paradigmatic claim made by the German authorities over the last three years whereby China is designated as a major trade target, in spite of the weaknesses and instability of this country's development model. Hence we can see a balancing of current accounts in the euro zone that result from the economic adjustments introduced in the countries in the south of Europe, via budgetary and wage cuts.

Under the traditional gold standard (1880-1914), countries submitted to a similar adjustment when their current account imbalances caused a decrease in gold reserves and endangered the fixed parity which they had to respect vis-à-vis gold. The central bank's discount rate was raised to attract capital and also to cool down the economy. This adjustment led to a decline in imports and via internal devaluation there was a progressive recovery in exports, even if this meant causing a recession. The essential point lay in the external balance and above all in the respect of gold parity on the part of the national currency.

From one excess to another

In the case of the "euro standard", these external deficits, a symptom of a crisis in the productive base, but especially of real estate bubbles, particularly in Spain and Ireland, and of a lack of any macroeconomic coordination within the zone (with mercantilist strategies in some countries which aimed to achieve permanent trade surpluses) were allowed to soar. The "bell rang on playtime" as the real estate bubble finally burst as a result of the US subprime mortgage crisis. Of course the rules of the game are different from those that applied at the time of the gold standard. It has not been a tightening of monetary policy that caused the credit crunch in these countries, but the repatriation of capital by the financial institutions in the north willingly provided to the south during the time of the bubble. It is important to stress that financially these cross-border investments simply mirrored the trade imbalances within the zone. In an integrated zone, a country in (trade) surplus is doomed to be the creditor of the countries in (trade) deficit. When, during a major financial crisis, a country which is greatly in surplus no longer wants to be the creditor of the countries in deficit, a credit crunch occurs amongst the latter, whose financial institutions owe their survival to support from the European Central Bank[5]. These capital outflows are equivalent to the increase in the central bank's discount rate that triggered macroeconomic adjustment, in the gold standard system.

But adjustment via the credit crunch (which was mainly a result of the financial crisis) was not enough. Like the zealous governments during the time of the gold standard a much wider adjustment rationale was introduced. Against a background in which economies had already been weakened by the credit crunch, with already skyrocketing unemployment and suppressed wages, the governments of countries that called on the EU and the IMF for aid had to implement draconian measures in terms of their public budgets and salaries. In the midst of full financial tension European leaders felt they had to obey immediately and quite ostentatiously the moral message which the capital markets are said to have delivered to them regarding the management of their public accounts. However the reality of the European crisis is linked to deeper problems than strictly budgetary issues.

The development of these macroeconomic adjustment measures notably led to the idea that a wage and budgetary drift had taken place in the countries in crisis, accused of having consumed beyond their means in the strict sense of the term. The accusation in fact relates more or less consciously to the issue of the trade and not the budgetary balance since before the crisis the countries with real estate bubbles had particularly low public debt levels and were therefore naively presented as the good boys in the European class.

The simplistic message about the supposed spendthrift countries found an unexpected echo in the first months of the crisis, since observers were particularly inspired when it came to pointing out the pariah and creating dubious acronyms (PIIGS, GIPSI). Simplistic messages had to be developed in real time, in order to satisfy a community of investors and analysts who were thirsty for expertise of an economic nature. The exercise became ridiculous when Italy was included in this group of European second zone countries, and especially with the threat to include France (designated as "the next on the list" by many observers[6], who imagined the bond market to be a methodological serial killer).

2. Analysis of unit labour costs: divergences without wage drift, influence of inflation gaps

The lack of conceptual references to analyse a crisis like that of the euro has often led to excessive notions based on the experience of monetary crises in the emerging countries. Over the last thirty years these crises have effectively illustrated the importance of current account imbalances as a symptomatic sign of not just monetary crises (in their most acute form) but especially crises of the productive base and of international macroeconomic coordination. Current account imbalances in the euro zone have been symptomatic of divergences in competitiveness notably caused by divergences in unit labour costs. Clearly minimal macroeconomic coordination was necessary on the introduction of the euro, in opposition to the noncooperative wage devaluation strategies on the one hand and strategies to create artificial wealth via real-estate bubbles on the other. After having allowed these imbalances to develop (going as far as challenging any concern raised about the issue[7]), it was decided once the crisis had started that everything had to be done to get rid of these imbalances whatever the cost in terms of growth. Hence we went from one extreme to another.

The canonical view of competitiveness divergence in the euro zone

Although the cases of the emerging countries which have experienced monetary crises are interesting, there has however never been a unique cause leading to current account imbalances. The archetypal emerging country affected by a monetary crisis is one in which there is a structural current account deficit making it dependent on the influx of foreign capital to finance its economy. In a country following this type of model, a budgetary and wage drift can, for possible electoral purposes, make the country's external deficits worse. This can cause for example excessive inflation, precipitate plummeting exchange rates and foster capital outflows, which deprive the real economy of its financing means and then create a vicious circle. If this country has pegged a fixed nominal exchange rate against a reserve currency like the dollar for example, we might expect the pressure to become insurmountable so that the central bank finally resigns itself to the currency's fall which can contribute, to a certain extent, to a macroeconomic re-balancing.

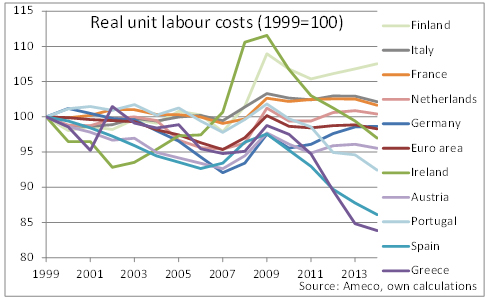

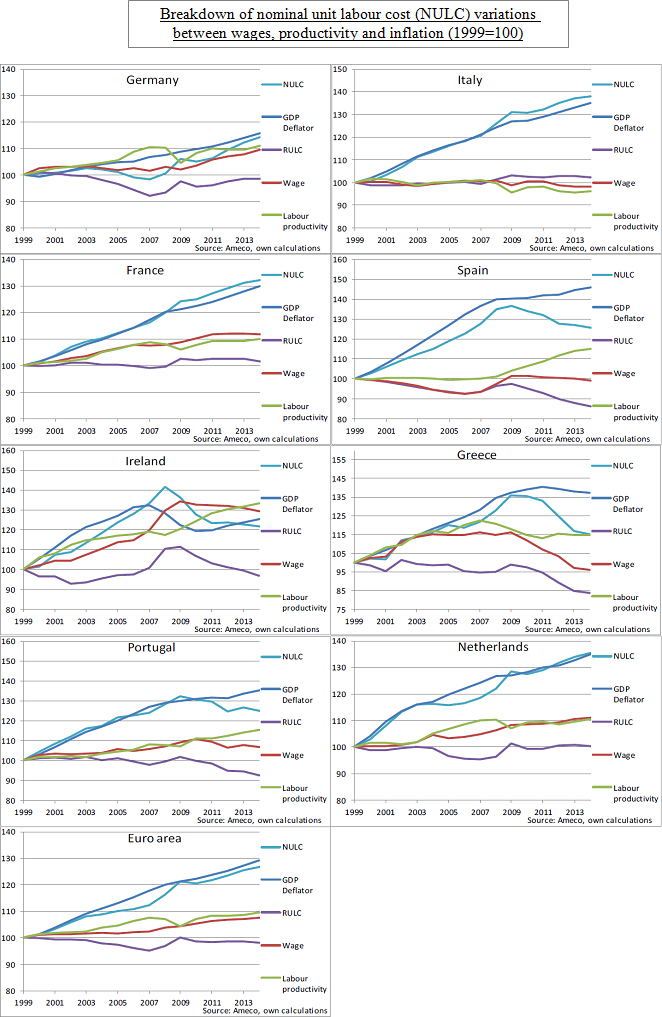

Contrary to common belief this situation does not typify the so-called peripheral countries within the euro zone, in the period prior to the crisis. In fact the canonical view of divergences in unit labour costs is basically limited to the following graph:

The divergence in nominal unit labour costs between countries effectively forms the core of the problem of trade imbalances[8]. But unfortunately this concept, which is central to any study of competitiveness, tends to be addressed in an extremely simplistic manner. Many analysts handle unit labour costs as if they were dealing with wages as such and often without even trying to see whether they are considering a nominal or real quantity. Before looking at the idea of nominal unit labour costs we should look at the following graph very carefully. Indeed we are dealing with a nominal variable to which inflation contributes but which, in the case of Germany, stagnated and even decreased from 2003 to 2007. The graph naturally gives the impression that there has been a drift in the so-called peripheral countries, and that "wages" soared by 40% in Ireland between 1999 and 2008, by 35% in Spain and by more than 25% in Italy[9].

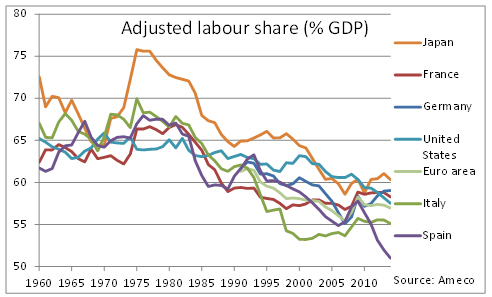

The decline in the wage share, an underlying trend

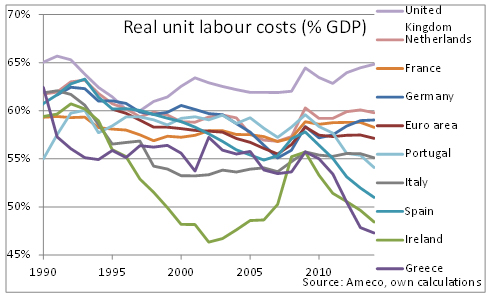

But a similar analysis in real terms indicates another kind of dynamic. Indeed as well as analysing developments over a longer period it is vital to make a distinction between the different variables that contribute to nominal unit labour costs and first and foremost, to isolate the direct contribution made by inflation. In real terms unit labour costs represent the share of wages in the economy[10]. This figure logically finds expression as a share of GDP[11]. First of all let us consider its development since 1999.

We see that the wage share in most euro zone countries, notably those on the periphery, dropped quite significantly between 1999 and 2007 and by around 7% in Spain. This observation does not match the idea of a wage drift. In France and Italy the wage share stagnated in the first phase of the euro's history before growing by around 3% between 2007 and 2009. In the context of the reforms initiated by Gerhard Schröder, real unit labour costs decreased in Germany by around 8% between 2003 and 2007. In Ireland we can see a sharp rise between 2002 and 2008 which should be placed in perspective with a significant decrease at the end of the 1990's and the beginning of the 2000's. Generally speaking the significant gap between nominal and real unit labour costs dynamics indicates the weight of divergences in inflation.

Beyond the share of wages in GDP, unit labour costs can also be considered as the ratio between the average compensation and productivity. To say that a country's real unit labour costs have decreased over a given period means that the average wage has not risen as much as productivity[12]. In principle real unit labour costs represent a ratio that should not really vary over time, neither decrease nor increase indefinitely[13]. We should note that for various reasons the wage share worldwide has tended downwards over the last four decades, mainly because of the decline in wage negotiation power and more generally as a result of the globalisation of production.

Conversely the share of profits has increased over the same period; this has notably provided significant support to stock markets over the last few decades in the developed world[14]. Moreover low salaries has meant lower demand which in turn has led to the development of real estate and credit bubbles, whose effects of artificial wealth has encouraged wishful thinking in the countries involved.[15] Against this backdrop, Spain stands out as one of the countries with the strongest decline in the wage share, along the line of 7%, between 1999 and 2007.

Beyond these relative developments we should consider wage share levels in the GDP per country. Again the statistical reality reflects a different message from the political and financial clichés. Not only has the wage share decreased in the peripheral countries generally it has done so from a relatively low starting point. In 1999 Spain lay far from the euro zone average and given the present adjustment it is heading towards even lower levels of around 50%. The adjustment is as evident in Ireland and Greece as they head towards levels below 50% from bases that were already below the European average.

Ireland's case is extreme given the range of variations in the wage share. The country undertook a major adjustment effort in the 1990's and in the early 2000's before giving up as suddenly to the backdrop of the real estate bubble until 2007. However, even at a peak in 2007, the wage share was below the euro zone average. Italy made a significant effort in the 1990's bringing its ratio down from 62% to 53% of the GDP without any notable increase after that. Over 20 years France has remained at a relatively stable level below 60%.

The burden of divergences in inflation

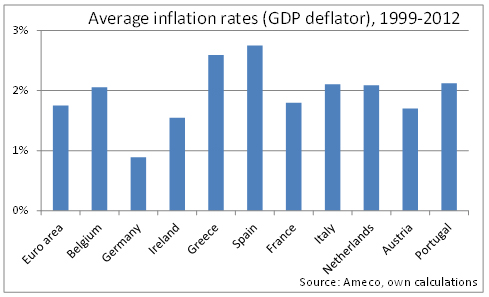

The divergences between the dynamic of nominal unit labour costs and their equivalent in real terms comes quite logically from the divergences in inflation between the countries in the euro zone from its very inception.

Here we mean inflation in terms of the GDP deflator and not the consumer price index (CPI). Beyond differences in the composition of the baskets the difference between the two ideas lies in the fact that the GDP deflator represents the inflation of production and not consumer prices, therefore excluding imports. This measure makes more sense when competitiveness is considered[16] and it is this which links nominal and real variables, as in the case of unit labour costs. From a statistical point of view we note the regime of under-inflation which typifies Germany with price increases between 1999 and 2012 equivalent to an average annual inflation rate below 1%[17].

Over 13 years Germany has seen prices rise barely over 10% whilst those in Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece have risen over 30%. Between 1999 and 2008 Ireland witnessed 40% inflation before prices dropped sharply during the economic turbulence. In France the increase has been around 25% which corresponds to an annual pace below the 2% limit (which is admittedly artificial). The Netherlands, which has a high trade surplus, has experienced a normal development in prices whilst Germany distinguishes itself quite clearly. We might then really speak of under-inflation in this country.

In a regime of fixed nominal exchange rates (and even more so in the monetary union therefore) divergences in inflation are equivalent to divergences in the real exchange rates between countries. Moreover the question of inflation is not independent of that of labour costs since under-inflation can notably come from marked wage moderation as implemented in Germany.

Breakdown of unit labour costs between wages, productivity and inflation

Continuing along this line of thought it is possible to put together a breakdown per country of the development of unit labour costs since 1999 between the contribution made by inflation (GDP deflator), the real average compensation and productivity. Unit labour costs are defined as the ratio between the real average compensation and productivity. The ratio between real unit labour costs (RULC) and nominal unit labour costs (NULC) is naturally inflation (GDP deflator). Hence we see the decisive importance of divergences in inflation (see graphs page 9).

The example of Italy is striking. The wage share (or the real unit labour costs) has barely risen over this period. Above all the development of nominal unit labour costs therefore reflects that of prices. Real unit labour costs have stagnated, for the simple reason that wages and productivity have followed a common trend of stagnation. Productivity gains have been zero, slightly negative even, likewise the average salary. The lack of productivity gains is a major economic problem but which must not be confused with a wage drift. These two problems are different and call for different solutions. Wage reductions whatever the cost, mass unemployment and more generally the economic confusion that goes together with a recession and a credit crunch only worsen the dynamics of productivity. This is what we could see in Portugal.

In Germany the decrease in real unit labour costs resulted (until 2008) from the productivity gains which were not felt in the average real wage (which only rose slightly over this period). These productivity gains were quite moderate, barely more than a total of 10% over nine years. France actually experienced a similar development in its productivity but over the same period the real average wage developed in line with productivity, which implies stable real unit labour costs. In Spain the real wage decreased over that period with stagnating productivity, resulting in a sharp drop in real unit labour costs. However the cumulative inflation of over 40% drove the nominal unit labours cost upwards. A healthy situation would comprise significant productivity gains, similar wage increases and an almost homogeneous inflation rate between the various countries of the euro zone.

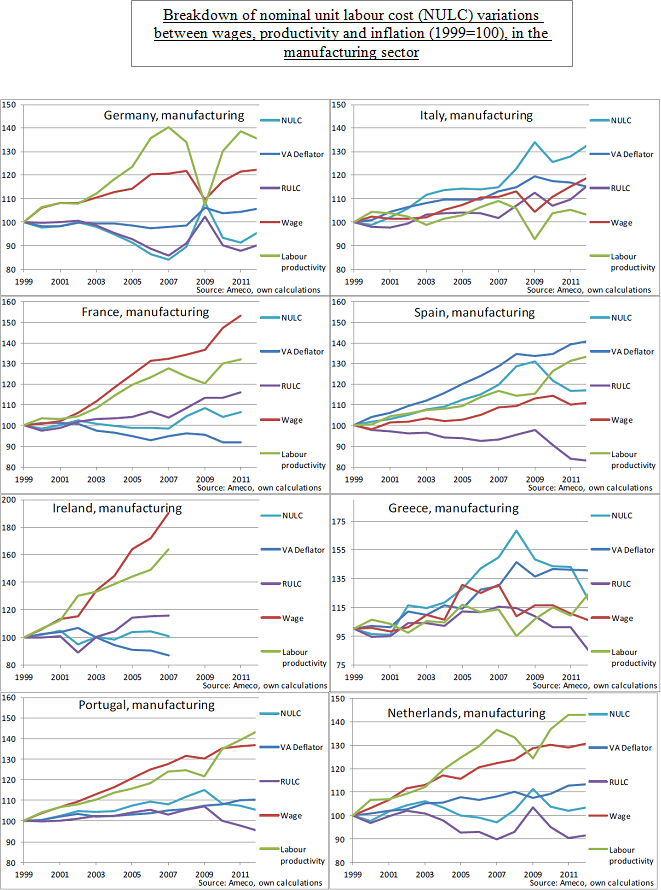

In the manufacturing sector, which is the most pertinent in terms of competitiveness, we can see similar trends, but the extent of it is even more striking. Hence in the first phase of the euro Germany experienced productivity gains of around 40% in all in comparison with wage rises of little more than 20%. It is therefore in the manufacturing sector that the strategy of "wage devaluation" has been the most evident.

In these calculations the average compensation is expressed in 'real' terms but in the sense of the sector deflator (and not of the GDP deflator). This means measuring how wage increases affect the dynamic of unit labour costs and competitiveness in this very sector. The measurement can therefore be very different from the notion of wages from the point of view of purchasing power, depending on the development of inflation in the sector. Hence in France the 'real' wage increased by more than 50% in the manufacturing sector but with a deflator that decreased by slightly less than 10%. Although Germany also experienced a slight decrease in its deflator in the first phase of the euro France was almost the only country to experience a phenomenon of manufacturing deflation, which is still ongoing. French businesses have tried to counter the competitive environment by a continuous decrease in prices to the detriment of profitability and in the end of investment. Wages increased normally, but in a context of price decreases, their relative burden has increased, all the more so in the face of Germany which launched a strategy of wage moderation. In Italy productivity gains have been slightly higher than those across the rest of the economy and a 'real' wage that has risen slightly more than productivity, leading to a rise in the wage burden in terms of value added. In Spain wages rose less than productivity to the extent that the development of nominal unit labour costs result more from inflation in the main.

These results again highlight that there has not been a wage drift but simply, as in France, an increasing wage burden because of the competitive environment. From the point of view of the sector as a whole, the idea of correcting excesses via wage reductions can only seem surprising. The problem of the peripheral countries mainly lies in their low productivity gains (and wages as far as the effect on demand is concerned), and in divergences of inflation with core countries. Most of these countries have not experienced manufacturing deflation comparable to that of France; which in relative terms might appear to be a drift due to its difference with the German competitive trend and notably its wage policy. Although recent wage increases in Germany are welcome in view of the differences that have appeared since 1999 with productivity, this increase is still modest and has not made it possible to catch up for the time being.

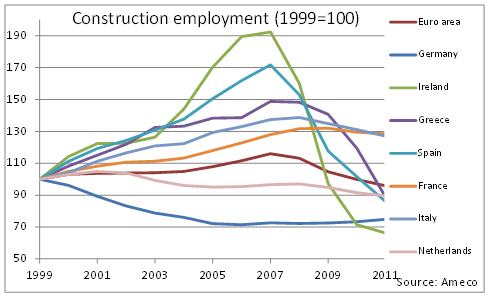

The real economic aberrations have occurred in the real estate sector but we should note that as a whole per country we cannot see a particularly acute drift in terms of wages. There was a wage drift of 20 to 30% between 1999 and 2007 in Ireland and Greece but not in Spain. Paradoxically it was after 2007 that the average wage rose sharply in the construction sector, because the lowest-paid employees were fired. Excesses in the sector mainly lay in the number of houses that were built; which led to mass job creation the economic interest of which was zero. This overemployment in the construction business in the "bubble'" countries led to the illusion that unemployment was being absorbed, the effect of which was all the greater when the bubble burst.

3. Vital European macro-economic coordination

These observations can but indicate the need for macroeconomic coordination between European countries. This coordination is vital within an integrated economic zone (notably from a financial point of view), and especially in a monetary union. Historically monetary union was introduced after several decades of permanent coordination work that aimed at monetary stability between the countries of Europe.

The cost of monetary convergence

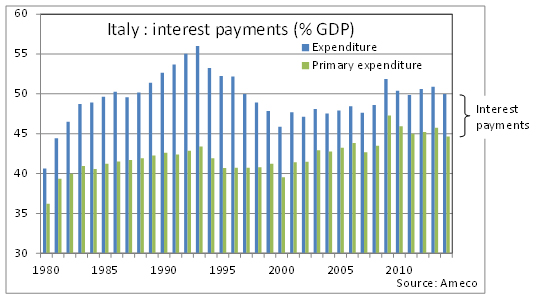

Italy is a good example of this attempt towards convergence. The country is known for its durably high debt ratio (over 120% of GDP). But the explosion of the debt in the 1980's (which marked the transition of a level from 60% to 120% of GDP) was mainly the result of exorbitant interest rates paid on the debt itself. These exorbitant rates were directly linked to the Bank of Italy's monetary policy which aimed to stabilise inflation and to establish the nominal stability of the exchange rate between the Lira and the Deutsche Mark. Hence Italy paid a high price for the effort it made towards monetary convergence from the point of view of the debt. In a bid to absorb the debt the authorities launched a series of structural and budgetary reforms as of the 1990's which led to a durable primary surplus[18]. In a context of high devaluation of the Lira which followed the collapse of the EMS in 1992-93, the country recorded a significant trade surplus. But as a whole these continuous economic and budgetary efforts weighed on growth. Without macroeconomic coordination and without any possible adjustment in terms of the exchange rate industrial powers like France and Italy have experienced an ongoing decline in their competitive position which in turn has led to long term trade deficits.

Managing the currency at the service of the economy

The monetary architecture has been a European concern for the last two centuries peaking in a global background of the long disintegration of the Bretton Woods system. The post-war period was marked by a continuous series of initiatives that aimed to build a stable monetary architecture, from the European Payments Union to the euro and the various forms of currency snake, including the European Monetary System (EMS). This concern is the corollary of cross-border activities which are central to the development of an integrated economic zone.

Once the euro was introduced policymakers allowed themselves to be carried along by the idea that by definition eradicating nominal exchange rate fluctuations made constant efforts towards coordination unnecessary . There was a kind of exhaustion in the face of the permanent, often difficult negotiations over the management of the European monetary architecture, in a sometimes tense context as it was when the EMS broke up in 1992-93[19]. In a dissipated context of economic understanding and as they concentrated on the issue of nominal exchange rates most political leaders gradually forgot about economic development and external balances. A series of threshold-ratios emerged in this situation the respect of which, even if it was artificial, was supposed to serve as economic coordination between European countries. This was the case with the famous 3% budgetary deficit rule, the economic context aside, was constantly and even systematically infringed. Given the complexity of the real situation these theoretical thresholds were increasingly unpopular and the recent idea of a public debt threshold (set at 90% of the GDP) which would threaten growth directly was actually rapidly rejected.

A single monetary policy naturally leads to divergences in inflation depending on the economic features of the countries involved and notably depending on their degree of development. It is therefore just as vital to coordinate macroeconomic policies particularly from the point of view of wages. In the context of monetary union a wage devaluation policy is double-sided; via wages themselves (direct effect) and via the ensuing disinflation, which reduces the real exchange rate of the country in question in relation to its partners. Monetary convergence is an advantage in that it facilitates the development of businesses and pan-European production chains (which leads to economies of scale and scope). But it is vital, whatever the monetary architecture, to take on board the cost of this convergence and to negotiate a means to assume it collectively Europe wide. The example of Italy illustrates this need. The main enemy of economic stability in Europe is the idea of a spontaneous economic order that would result from any type of monetary project long term. More generally these requirements of productive balance in Europe must be the focus of any political project for Europe, especially if we are talking of "social Europe" which can only exist in a context of economic stability.

Conclusion

Paradoxically the focus on issues of divergences in nominal unit labour costs in the euro zone shows that in spite of excessive simplifications a certain amount of progress has been achieved in understanding how monetary structures function. The problem lies in the biased interpretation of these competitiveness indicators. The idea of the "economic government" of the European Union has therefore evolved as economic understanding has progressively developed. Whilst this idea referred strictly to budgetary issues, macro-economic imbalances aside[20], an additional notion was introduced as part of the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP). This includes the basic variables of external imbalance, including the current account balance and the variation in nominal unit labour costs[21]. Although it is beneficial to systematize the political follow-up of these vital measures this study has illustrated the errors of interpretation than can come from this especially in regard to unit labour costs. The myth of the wage drift in the peripheral countries is one example. The idea of allowing these imbalances to grow and then demand their clearance as a matter of urgency is incompatible with the idea of a single currency since these adjustments are difficult to bear without devaluation. The economic destruction caused by the rapid clearance of external imbalances via domestic devaluation (budgetary and wage cuts) is a grave threat to the stability of the European Union.

Moreover given the impact of non-cooperative wage policies and the mirroring of the American real-estate bubble we should consider the global context in which these imbalances have developed within the monetary union. There is no doubt that pressure on wages in Germany (matching the economic paradigm developed by Gerhard Schröder) notably comprised a response to globalisation and the mercantilist competition of some major emerging countries like China. Because we focus mainly on intra-European issues, we often tend to forget the global factors involved in divergences, notably the political ones, which have formed in the euro zone. The debate over the dumping of solar panels by China is a good example of a divergence of interest that developed between France and Germany because of their different industrial positions, in terms of cost structures and foreign trade strategies. Although these divergences were stronger than the anti-dumping measures put forward by Karel de Gucht the latter raised a question which is central to European imbalances, both internal and external. It should be a priority of European policy beyond budgetary issues that often do not consider basic economic stakes.

Finally financial risk management is a vital issue particularly when it comes to decoupling the banking and sovereign spheres, in what we might more or less call banking union. Likewise the ECB's role is vital and we cannot be but impressed by Mario Draghi's craft. But out of political despair and by believing that in one way or another we can ignore the issue of economic divergence we are expecting salvation from an institution which although extremely powerful, finds itself at the crossroads of extremely different monetary traditions, to a backdrop of sometimes opposite political landscapes. The same applies to eurobonds which often are the source of deep disbelief in most northern countries. Beyond politico-monetary options it is vital to address the problem at base, i.e. to ensure that all the countries of Europe gradually recover a viable competitive position thanks to progressive cross-adjustments.

[1] The two Harvard researchers used macroeconomic data in a looser manner to assert that the growth rate of a country whose debt ratio lay over 90% would halve. But beyond this study's methodological inadequacies it was used above all as a scientific guarantee in the quest for budgetary austerity implemented as a solution to the crisis.

[2] On the basis of this observation the IMF changed its stance on the issue of multipliers which notably enable the assessment of the impact of austerity policies on growth and the debt dynamic. The mea culpa on the part of the Fund regarding Greece revealed increasing divergences with the European authorities over the crisis management strategy. In this context the IMF is now moving increasingly towards the idea of restructuring the debts of insolvent States in the euro zone.

[3] In terms of the current account balance and the external debt, history offers extreme cases of external debt clearances at the price of economic collapse. In the 1980's Romania was one of these examples which are far more extravagant than those in the euro zone. Having borrowed from the West to fund its industrial development the country witnessed soaring debt levels and in a hostile international financial environment the latter tripled between 1978 and 1980 to total $11 billion. After many years of budgetary cuts, wage reductions and food shortages Romania finished reimbursing all of its external debt in 1989. See: Monica Susanu, Romanians' Public Debts Saga, University of Galati, 2010.

[4] Daniel Gros's analyses (available on the CEPS website) provide a particularly pertinent view of the link between current account imbalances and the sovereign debt crisis. See: Daniel Gros, External Versus Domestic Debt In The Euro Crisis, CEPS Policy Brief No. 243, May 2011.

[5] Paul de Grauwe and Yuemei Ji made an enlightened challenge to the controversy over the link between the Target 2 system and current account imbalances based on the realistic hypothesis that European savings in German banks would not be converted into deutschemarks if the euro zone collapsed. This polemic of which Hans Werner Sinn became the champion maintains that current account imbalances end up in the central banks' balance sheets (firstly as a Bundesbank claim vis-à-vis the national central banks of the peripheral countries) via the Target 2 payment system and that this involves a significant threat to German taxpayers. See: Paul de Grauwe, Yuemei Ji, What Germany Should Fear Most Is Its Own Fear, CEPS Working Document No. 368, September 2012.

[6] See for example: "The Time-Bomb At The Heart of Europe", The Economist, 17th November 2012.

[7] The trend to play down the importance of current account imbalances naturally had its global counterpart. Hence until 2007 it was customary to maintain that the US trade deficit was not the symptom of a structural problem. It was even said that financial flows from abroad towards the USA resulted from financial innovation with virtues comparable to those found in science and industry.

[8] Unit labour costs basically represent the ratio between a country's total wage bill and its GDP. In nominal terms, it is the ratio between the nominal wage bill and real GDP. Nominal ULCs can only be expressed in terms of variations or as an index (base 1999=100 in our calculations). They represent the labour costs that are necessary to produce one unit of real GDP, on average. Also, it can be calculated as the ratio between the average wage and productivity. For the average wage, we divide the nominal wage bill by the number of employees and, in the case of productivity, we divide real GDP by the country's total workforce. Nominal ULC variations are a good competitiveness indicator in terms of labour costs. However it is often interpreted in a very simplistic manner. Variations in nominal ULCs result of variations in wages indeed, but also in productivity and inflation. This study notably shows that divergences in inflation have been a decisive factor for divergences in nominal ULCs within the EMU.

[9] All data used for the analysis of unit labour costs are from the European Commission's Ameco online database (data retrieved in July 2013).

[10] Here we shall use the idea of adjusted unit labour cost, which includes independent workers considering that they receive the same average salaries as employees.

[11] In real terms ULCs represent the ratio between total real wage bill and real GDP (or as an equivalent the nominal wage bill and the nominal GDP). Real labour unit costs can therefore be expressed as a share of GDP and not just as variations or as an index number (unlike nominal ULCs). Likewise it can be calculated as the ratio between the average real compensation and real productivity. Their variations result from the development of real wages and of real productivity (and exclude inflation).

[12] During the entire study we shall consider the average compensation per capita and productivity per capita (and not hours) in a bid to have a comparison and homogeneity of data between countries and to facilitate the calculations of the breakdown of nominal labour unit costs between average wages, productivity and inflation (GDP deflator).

[13] The hypothesis whereby the wage share is said to be constant is known in economics as Bowley's Law.

[14] This world trend which is not challenged in the present context provided significant support to profits and stock market performance, on top of non-conventional policies on the part of central banks over the last few years.

[15] Without ruling out the impact of phenomenon like corruption of course which tend to go hand in hand with real-estate bubbles.

[16] The idea of the deflator would also make more sense in terms of inflation targeting, since it excludes directly exogenous factors. It would avoid condemning the economy to slowig to compensate import price rises whether they were linked to energy or manufacturing.

[17] By average we mean here geometric mean, i.e the inflation rate that, if constant, would have led to the overall variation in the price level that was observed over the period from 1999 to 2012.

[18] To this we might add various financial tricks that aim to clear part of the debt and by way of derivatives to satisfy as a matter of urgency the budgetary criteria required to join the euro.

[19] Barry Eichengreen's book, The European Economy Since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond (Princeton University Press, 2008) offers an enlightening analysis of the economic difficulties that surrounded the various attempts to achieve monetary stability during the post war period.

[20] The 3% threshold on public deficits, 60% on the debt ratio, pace of public spending growth capped by mid-term potential GDP growth with a certain flexibility in times of crisis. See The EU's Economic Governance Explained, European Commission 10th April 2013.

[21] In addition to this there is notably the country's net international investment position, the variation over five years of export maket shares measured in values and the variation over three years of the real effective exchange rate. From the point of view of internal imbalances, the approach notably takes public and private debt ratios into account as a share of GDP, real estate prices, unemployment and the annual change in the financial sector's total financial liabilities. See: Scoreboard For The Surveillance of Macroeconomic Imbalances, European Commission February 2012. < http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2012/pdf/ocp92_en.pdf>

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :