Democracy and citizenship

Thierry Chopin,

Jean-François Jamet,

François-Xavier Priollaud

-

Available versions :

EN

Thierry Chopin

Jean-François Jamet

François-Xavier Priollaud

Introduction

Along with the crisis fundamental questions about the future of European integration have been raised. In order to recover their sovereignty vis-à-vis the markets and thereby the ability to decide about their future, the States of Europe – notably the euro zone members – have understood that they have to form a more coherent union. As a result the idea to form a banking union has progressed rapidly over the last few months. The debate continues on points of disagreement in terms of budgetary union (notably the timeliness of pooling part of the debt), but stricter, common rules have already been adopted and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is soon due to enter into force.

Given the transfer of competences that these joint measures imply, it is now impossible to elude the question of political union. European decisions must enjoy adequate legitimacy in the eyes of the citizen and decision-making mechanisms must be sufficiently simple and clear enough for them to be effective and transparent. Without this the citizens will not accept economic union and questions will continue to be asked about the political vision behind European decisions. In the end it is economic integration as a whole that will be weakened and may even find itself under threat.

Debate has started in several Member States – notably at the highest level in Germany. However the debate about these issues does not seem very structured. Angela Merkel seems to be saying that she wants a new Convention and José Manuel Barroso, President of the European Commission, has spoken in support of "a democratic federation of Nation States" [1]. Conversely Mario Draghi, the President of the ECB believes that "those who claim only a full federation can be sustainable set the bar too high" [2]. Furthermore, whilst many taboos have now been broken as far as economic integration is concerned, debate of the political and democratic aspects of the reform of the European institutions is lacking in many Member States, notably in France.

As part of its task the "Group of 4" is now looking into this (Herman Van Rompuy, Jose Manuel Barroso, Mario Draghi and Jean-Claude Juncker). This group delivered a first report during the June European Council ("Towards Genuine Economic and Monetary Union" [3]) and pinpointed four structuring issues: an integrated financial framework, an integrated budgetary framework, an integrated economic framework and a strengthening of democratic legitimacy and accountability.

Although the first three points have been the focus of a great deal of thought over the last few months [4], the latter has been left out of the present debate. Some papers have been written on the subject [5], the last one being the contribution signed by 11 Member State Foreign Ministers, which can be considered as the first attempt to formalise a draft for "Political Union" at the highest level [6].

The 27 Member States and European Parliament have to adopt a position on this issue as part of the consultation that the Presidency of the European Council launched mid-September [7]. This consultation aims to identify "what is feasible in the short-term and what is desirable in the longer-term."

In this context the present paper identifies a certain number of real, achievable proposals, both from a political and legal point of view. This means providing detailed, operational content to the project to strengthen the democratic legitimacy [8] and accountability of European institutions. These proposals also aim to strengthen the effectiveness and clarity of the decision-making system.

This paper thus focuses on:

- justifying the need for legitimating and strengthening political and democratic control as part of the reforms that aim to implement an integrated financial framework, an integrated budgetary framework and an integrated economic policy framework;

- defining the proposals enabling the achievement of the objective to strengthen political legitimacy and the efficacy of democratic control [9];

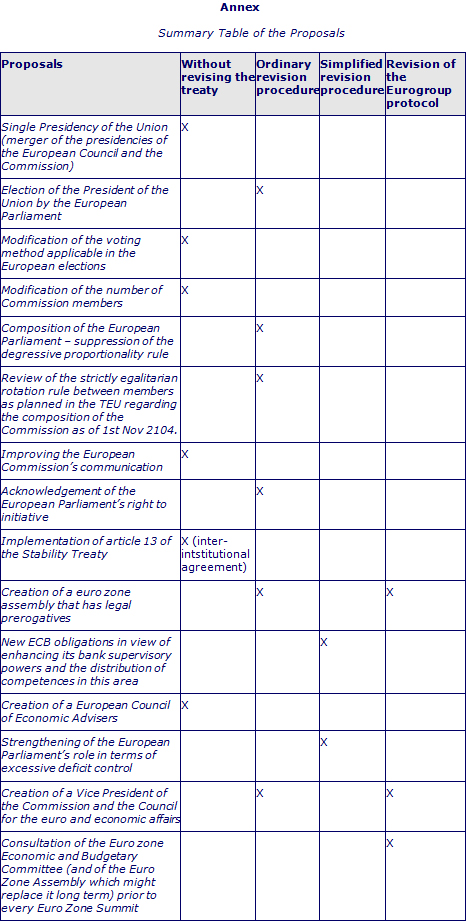

- analysing the legal feasibility of these proposals by identifying the type of reform they involve: innovation using the treaty as it stands; limited changes to the Treaty under the simplified revision procedure as planned for in Article 48 of the TEU; or more important changes to the Treaty under the ordinary revision procedure as planned for in Article 48 of the TEU.

1. The Need for Democratic Legitimacy and Accountability

The need for democratic legitimacy has emerged quite clearly in the context of the present crisis and the reforms adopted or anticipated to resolve it. The report by the Group of 4 highlights it quite explicitly: "Decisions on national budgets are at the heart of Europe's parliamentary democracies. Moving towards more integrated fiscal and economic decision-making between countries will therefore require strong mechanisms for legitimate and accountable joint decision- making. Building public support for European-wide decisions with a far-reaching impact on the everyday lives of citizens is essential."

The polls reveal in fact a decline in citizen confidence regarding the main European institutions (Eurobarometer 75, spring 2011). Since the spring of 2010 the mistrust of those interviewed has increased by 8 points regarding the ECB, 7 points concerning the European Parliament, 6 points vis-à-vis the European Commission and the EU Council. Moreover the trend is unprecedented, and for the first time there is more mistrust than confidence in the four institutions quoted above. Another survey (Eurobarometer 76 autumn 2011) showed that satisfaction with the way democracy works in the Member States declined but still held the majority (52 against 46), but when the question focuses on the Union the decline is greater and this opinion now only just holds the majority (45 against 43). Lastly, the most recent Eurobarometer Standard 77 in the spring 2012 confirms the decline in citizen confidence in the European institutions: 31% of those interviewed say they trust them (-10 points since the spring of 2011), i.e. the lowest level ever reached. Unsurprisingly the citizens who are least confident in the European institutions come from the Member States most affected by the crisis (Greece and Spain notably), as well as from countries where Euroscepticism is traditionally strong (UK). The present situation is typified by a context of extreme mistrust, a problematic situation for the European institutions which do not enjoy enough legitimacy at a time when they are being called upon to take decisions in sensitive areas that affect the very heart of democratic sovereignty, such as budgetary policy.

In addition to this the economic crisis raises a challenge in terms of leadership, coherence and also effectiveness for European governance. In a crisis situation, which demands that the European Union and its Member States provide answers to the challenges raised, to their frustration Europeans discover the limits of European governance and its "executive" deficit: the weakness of the European executive power; the stratified nature of the community institutions and its corollary, a lack of clear political leadership; competition between the institutions and the States; slowness of the negotiation process, etc. [10] Above all to date the European Union has shown that whereas it is able to produce rules, it remains weak in making discretionary choices, which are nevertheless vital in a period of crisis. At its base European governance is suffering from an imbalance between the relative strengths of national diplomacies and European democracy. Although the States still consider themselves as sovereign and the arbiters of last resort in terms of the decisions to take in times of crisis, the weaknesses of European governance revealed by the financial crisis call for an analysis of the conditions required for European political leadership. While the Union is, of course, a Union of States it is also a community of citizens and the creation of true European leadership necessarily means a strengthening of the unity of the European political corps. If we agree with the idea that popular will is the basis of the legitimacy of power in our democratic regimes, then European Union cannot escape this rule. But what do we see other than a lack of democratic competition in the appointment of the main European leaders? For example there is no political competition in the appointment of the President of the Commission; the election of the President of the European Parliament is undertaken on the basis of a bipartisan consensus and last but not least, the appointment of the President of the European Council is not organised according to a minimum of democratic rules which we would expect to have in fo a position like this: presenting oneself as a candidate, political competition between several candidates, public, transparent debate etc. True European political leadership supposes greater popular legitimacy, the base on which it should be built. What is at stake here lies in making, even a partial, transfer of the source of the Europe of State's legitimacy over to the citizens. This additional democratic legitimacy would lead – as part of the present system – to a strengthening of European political leaders' ability to act and take decisions in the face of national political leaders.

Moreover the rise of extremism and populism is a symptom of Europe's legitimacy crisis. From Sweden to Hungary, including France, Denmark, Belgium, Norway and Greece, the different general elections confirm the strength of the far right and of populism that promote protectionism as regard economic, cultural and even identity matters. This anti-European extremism and populism criticise the power held by the national and European elites. They find their support in challenging the political and democratic legitimacy of the European institutions. They fiercely criticise the weaknesses of the institutional mechanisms that produce democratic legitimation of European decisions and reject the present European political and economic system. [11].

The question of the legitimacy of European decisions has become increasingly acute over the last few years. The European Union has been experiencing an unprecedented legitimacy crisis since the 1990's. The best informed analyses highlight a progressive structuring in opinion (1980's and 1990's) then a slow "politicisation" (revealed during the referenda in France and the Netherlands in the spring of 2005 and then in Ireland in 2008). This slow process of "political learning" on the part of the citizens has put an end to the "permissive consensus" [12] which typified public opinion about "Europe" since European integration was launched: there is not one Member State in which the citizens will now "blindly" trust their elites to manage best their European interests [13].

Part of Euroscepticism feeds on what is seen as the European Union and the euro zone's political and democratic weakness. Remedying the present confidence crisis therefore supposes providing real answers to this problem.

2. Political and Institutional Proposals

In this context several solutions might be put forward to strengthen democratic legitimacy and accountability.

2.1 Strengthening European Leadership

• Merging the presidency of the Commission with that of the European Council would strengthen the political clarity and democratic legitimacy of the European Union and help Europe to speak with one voice. The Lisbon Treaty allows for this innovation: it was to create this possibility that the ban on also having a national mandate was retained in the Lisbon Treaty whilst the ban on having more than one European mandate was withdrawn. The European Council would just have to appoint one single person for the two posts. Using this possibility would strengthen the political legitimacy of the person holding the title, who would thereby enjoy both community and intergovernmental legitimacy; he would also be responsible politically to the European Parliament. From this standpoint the President of the Commission would also preside over the European Council.

A change like this would not require a modification to the treaties. An inter-institutional agreement would be enough [14].

• Electing this president by direct universal suffrage, as suggested by the CDU during its Leipzig Congress in November 2011, would provide direct democratic legitimacy and also a clear political mandate to the EU President. Alternatively, and this option could be more realistic in the short term, he could be appointed by the European Parliament – as anticipated in the Lisbon Treaty – on the basis of the result of the next European elections, being himself the lead candidate. This would then be an election by indirect universal suffrage according to the model in application in most Member States (parliamentary democracy).

Any reform whereby the President is no longer elected by the European Council alone, after the merger of the presidencies of the European Commission and Council, would require a revision of the treaties according to the ordinary procedure (intergovernmental conference – IGC – preceded by a Convention, except if the European Parliament is not against the absence of a Convention). However if the treaties are taken as they stand the European Council might also offer as President of the Commission the candidate put forward by the winning party in the European elections (which would fall in line with the obligation included in the treaties for the European Council to take on board the result of these elections), and elect as President of the European Council the President of the European Commission.

• In regard to the European elections it would appear appropriate to ensure that the lists put forward by the national parties belonging to a European party share the same name and programme in all of the Member States. Each party should also put forward a candidate for the post of President of the Commission so that the election stakes are clearer for the electorate. Furthermore, one of the problems to solve regarding the European elections is that of defining clearer political majorities, which is not the case at present [15]: this would help to strengthen the link between the will expressed by the electorates and MEPs. With this in view the proposal to grant a "majority bonus" to the political party that wins the elections [16] deserves to be explored as part of a reform of the voting method employed in the European elections.

Any change in the method employed to elect MEPs requires a revision of the Council decision on the election of MEPs. In line with article 223 of the TFEU the means to elect MEPs are set by a unanimous Council decision after the approval of the European Parliament by a majority vote of its members. To enter into force this decision has to be ratified unanimously by the Member States.

• Redefining the composition of the European Commission. Since it plays a vital and unique role in the functioning and equilibrium of the European institutions the question of its composition is of the essence because its legitimacy depends on this to a large extent. There are several possible paths in view of breaking away from the equal "representation" principle enjoyed by the Member States within the College of Commissioners. The "presidential" model (the President of the Commission puts his College together quite freely) would be coherent with the election of a President of the Commission by direct universal suffrage. The "ministerial" model would enable the President of the Commission to choose the portfolio given to the commissioners (without negotiation taking place between the States) and rank these with the creation of the posts of "Deputy Commissioners".

It is possible to change the number of members of the European Commission without modifying the treaties via a simple decision on the part of the European Council acting unanimously (art. 17§4 TEU). However a change to the rules governing the Commission's composition, which breaks away from the equal rotation principle between the Member States and the principles set by article 244 TFEU would require a revision of the treaties according to an ordinary procedure (IGC preceded by a Convention).

• Improving the European Commission's communication. The College of Commissioners should publicise its weekly meeting more than at present. Its work remains relatively confidential, whilst in many ways it is the same as that of a council of ministers. One of the reasons is that the college meeting's minutes are published a week after the event only. At the very least a press release summarising the main points addressed and the main decisions taken should be published on the very same day. Finally a European audiovisual agency might be created to do more than the existing initiatives (Arte, Euronews).

This reform could be done with the treaties as they stand.

2. 2 Involving the National Parliaments in Economic and Budgetary Supervision

In terms of strengthening democratic legitimacy the national parliaments and the European Parliament have a decisive role to play.

• The implementation of article 13 of the Treaty on Stability [17] would increase involvement on the part of the national parliaments in the decisions taken concerning budgetary control and thereby strengthen their democratic legitimacy. This might be achieved initially on the basis of a "euro zone Economic and Budgetary Committee", comprising the members of the European Parliament's Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee (except for those whose States have not ratified the Stability Treaty) as well as the chairs of the finance committees and the economic affairs committees from the Member States' parliaments. The Committee would adopt initiative reports and issue opinions or resolutions.

The means for the implementation of article 13 of the Stability Treaty could be set as part of an inter-institutional agreement.

• The question of the creation of a euro zone assembly involving representatives from the national parliaments and the European Parliament could be debated as a possible extension of the experiment facilitated by the implementation of article 13 of the Stability Treaty [18]. Representatives from the States that use the euro or which want to join the euro would take part in this assembly. Depending on the subjects addressed, only the representatives from the States that have adhered to the corresponding supervisory mechanisms (for example the Stability Treaty, the Euro Plus Pact, etc.) would have the right to vote. It might bring together the members of the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee of the European Parliament (except for those representing States that do not want to join the euro) as well as a number of national MPs per Member State, whose number would be strictly set according to the population of that State (except for the guarantee given to every State of having at least one or two representatives from its parliament) [19]. The national parliamentarians would be appointed according to the rules used to appoint parliamentary committees in the national parliaments.

The creation of an assembly like this might at first be done without changing the treaties, as was the case with the COSAC [20] in 1989, which was not part of any legal framework. Its existence would however only be political and a change to the treaties would be necessary so that the positions it adopts have a legal value.

• The euro zone economic and budgetary committee, then the euro zone assembly that might subsequently replace it, would be given a role in the economic and budgetary supervisory mechanism that is anticipated for the Member States of the Economic and Monetary Union. These bodies would meet in regular sessions; it would also be possible to convene complementary extraordinary sessions. On the base of the reports presented by the Member States and the Commission (which should lead to a consolidated view of the public accounts in the euro zone), but also by investigations that might be launched on its own initiative, these institutions would guarantee the strength of the euro zone and the respect of the commitments made by the Member States (a qualified minority of MPs might be given the power to turn to the European Court of Justice in the event of breach). They would also need to know the progress achieved in the implementation of measures as part of the conditions governing the aid programmes. These institutions would be able to convene hearings with the national ministers, the President of the ECB and the President of the Eurogroup. They might also be consulted regarding specific appointments linked to the governance of the euro zone.

A revision of the treaty would be necessary in view of the simplified procedure in article 48§3 TFEU. However according to the perimeter of the euro zone economic and budgetary committee's competence and then possibly that of the euro zone assembly, a change to the treaties according to the ordinary revision procedure (IGC preceded by a convention) cannot be ruled out.

• The ECB ought to give more detailed account of its monetary policy including to the national parliaments. In particular it should explain to the euro zone's economic and budgetary committee (then to the euro zone assembly that might replace it) the effect of its policy on monetary aggregates [21] and on the economies of the various Member States, explaining whether it is adequate for a given national situation or how its national, sub-optimal effects should be compensated for, notably by the use of economic policy instruments that remain under the Member States' control. Finally the euro zone's economic and budgetary committee (then the euro zone assembly) might have confidential access to the minutes of the recent decisions of the ECB council of governors, as well as to adequate information concerning the ECB's results and financial activities before the audition of its president.

An institutional change in the monetary area would be possible according to the simplified revision procedure anticipated in article 48 §6 TEU but would require a decision on the part of the European Council acting unanimously after consultation with the European Parliament, the Commission and the European Central Bank.

• In order to strengthen the technical expertise, which MPs might use, a European Council of Economic Advisors could be created and might therefore be referred to by the European Parliament and the institution assembling national and European parliamentarians (economic and budgetary committee of the euro zone then the euro zone assembly). They would be able to ask the opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) in order to have the point of the view of the representative body of European civil society.

The creation of a European economic analysis council would be possible with the treaties as they stand.

However it would seem appropriate to include in the treaties an explicit opportunity for the European Parliament to refer to it (likewise to ask the opinion of the EESC). This would require a modification to the treaties according to the simplified revision procedure based on a unanimous European Council decision (art.48 §6 TEU).

2. 3 Strengthening the legitimacy and role of the European Parliament

• Greater proportional representation would strengthen the democratic legitimacy of the European Parliament. The present composition is far from the principle of democratic equity in terms of representation: the number of MEPs per inhabitant is for example twice as high in Finland as it is in France. But since citizens all have to have the same political rights in a democratic system, their vote should also have the same weight [22]. In others words the number of inhabitants per MEP should be same in all countries (with a minimum representation however to guarantee that even the least populous Member States are represented) [23], which is an objective criteria that is hard to criticise. Given the substantial increase in the powers of the European Parliament over time, enhancing the democratic legitimacy of this institution, which incidentally is the only one to be elected by direct universal suffrage, is a true stake, as the jurisprudence of the German Constitutional Court regularly points out. [24].

A modification like this would require a revision of article 14 §2 TEU according to the ordinary treaty revision procedure (IGC preceded by a Convention).

• Acknowledging the European Parliament's and Council's joint right to legislative initiative. The "monopoly of initiative" enjoyed by the European Commission only applies to the "community pillar". Indeed in the second (common foreign and security policy) and the third pillar (justice and internal affairs) the Member States have a joint right to initiative with the European Commission. It might be appropriate to extend this rule to the policies in the community pillar, not with the aim of restricting the Commission's prerogatives, but rather to add a democratic element to the initial stage of the decision-making process. Sharing the initiative between the Commission (which would retain this prerogative), the MEPs and the governments of the EU Member States (in the shape of a joint right to initiative between these two branches of European legislative power) would be valuable for two reasons, in comparison with the system in force at present: firstly it would meet the democratic requirements that form the base of representative democracy (in which the executive and legislative bodies share the power in putting laws forward); to give the citizens the feeling that they are being heard and that their European and national representatives are able to convey their will [25]. This innovation might be presented as a complement to the citizens' right to initiative introduced by the Lisbon Treaty.

A modification such as this would require a revision of the treaties (art. 225 TFEU) according to the ordinary procedure (IGC preceded by a Convention).

• Give the European Parliament the opportunity to play a greater role in terms of supervising excessive deficits as part of a modification of article 126 TFEU. The European Parliament should in particular be able to decide by a simple majority on the launch of an excessive deficit procedure on the basis of a recommendation made by the Commission if the Council decides not to follow the Commission's opinion.

This reform would require a modification to the treaty according to the simplified revision procedure of article 48 § 6 TEU.

2.4 Giving greater democratic legitimacy to the Eurogroup's decisions and to the euro zone summit

• Creating the post of Vice-President of the Commission and the European Council responsible for the euro and economic affairs – so that there is a European Finance Minister as called for by Jean-Claude Trichet [26]. This person would jointly take on the role of Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs and President of the Eurogroup. He would enjoy the status of Vice-President of the Commission and of the Council. He would be supported by the Eurogroup Working Group, for the preparation and follow-up of the euro zone summit meetings. Under his authority he would have a general secretariat – the Treasury – of the euro zone whose range of tasks would comprise the goals set by the present budgetary supervision and the future budgetary union. As part of the revision of article 136 TFEU, he would be able to put decisions forward concerning the euro zone. Such power of initiative could also be jointly given to the Euro Zone Assembly and to the Eurogroup. The measures put forward would be adopted in co-decision by the Eurogroup and the Euro Zone Assembly [27].

This would require a modification of the treaties according to the ordinary revision procedure anticipated in article 48 TEU (IGC preceded by a Convention).

• Prior to any Euro Zone Summit decision the body convening the national and European parliamentarians (the economic and budgetary committee of the euro zone and mid-term the Euro Zone Assembly which could replace it) would be consulted. It would vote according to a simple majority of its members. The president of this body would also be invited to the euro zone summits so that his opinion can be heard.

This modification might come as part of a revision of the Eurogroup Protocol.

• The Vice-President of the Commission and of the European Council responsible for the euro and economic affairs would be the euro's political face and voice He would be responsible for the communication of the Eurogroup's decisions (spokesperson) and for representing the euro zone amongst the international financial institutions. He would be responsible for explaining how the policies (budgetary, fiscal, wage etc..) of the euro zone Member States form a coherent policy mix with the ECB's monetary policy. Finally he would speak regularly within the euro zone's national parliaments.

The tasks of this Vice-President of the Commission and of the Council responsible for the euro and economic affairs could be defined as part of the Eurogroup Protocol.

2. 5 Guaranteeing the legitimacy of the extension of the powers of the ECB regarding banking supervision

• The ECB will have to explain regularly its action to the European Parliament as part of the competence it is due to be given in terms of banking supervision [28]. The auditions and corresponding reports should be strictly separate from its monetary activities. Moreover the ECB will have to explain and submit for approval by the European Parliament the strict procedures that it would set in place to guarantee that its supervisory activities do not alter its work toward monetary goals and that it would be protected from the "Stockholm Syndrome" [29] as far as the banks that it would be supervising are concerned. The European Parliament should be able to request an audit of the procedures and of their implementation and also be able to dismiss the president of the ECB if he commits a serious error in terms of banking supervision (as is the case in its present competences).

The proposal implies an institutional modification in the monetary area which would require a revision of the treaties according to the simplified procedure included in the article 48 § 6 TUE, on the basis of a unanimous decision taken by the European Council.

3. What methods should be used?

The new Europe will not be built in the same way the "founding members' club" was built. We shall have to draw up new methods for the integration of Europe over the next 50 years. The "community" [30] and the "intergovernmental" methods [31] are no longer adequate to face three simultaneous challenges comprising democratic requirements, an increase in the number of Member States, and the effectiveness of the decision making process imposed by crises and the pace of globalisation. It is within this context that we suggest deeper thought on the three methods that will make it possible to rise to these challenges without waiting for possible modifications to the treaties.

3.1 The "Convention" Method – a response to democratic requirements

One of the ways to democratise the functioning of the European Union lies in strengthening national parliamentary representation, particularly in terms of the political control of European decisions. Indeed the added value provided by national MPs does not lie as much in a technical control of the drafting of EU norms as in a political approach to European issues. In this regard the convention has proven its worth by rallying complementary legitimate bodies: national MPs, MEPs, government representatives, members of the European Commission.

To date two conventions have been created: in 1999 to set out the European Union's Charter of Fundamental Rights; in 2002-2003 to draft the constitutional treaty. In view of these successful experiences concerning the method used (and regardless of the difficulties encountered in ratifying the European Constitution whose opponents criticized it precisely because of the lack of place it gave to progress in terms of democratic legitimation and clarity of the decision making system), the convention seems particularly adapted to move forwards along the path of European general interest on issues that are the focus of major political difficulty.

Planned for in the Lisbon Treaty, in some cases where the treaties might be revised, the conventional method may be used more for the purpose of political goals, and not in terms of revising the treaties. The conventional method indeed enables the positive conjugation of the various legitimate bodies without interfering in the functioning of the institutional "triangle".

Specialised conventions – whose composition would vary depending on the subjects being examined – might be convened by the European Council that would provide them with the mandate, not to legislate but to define proposals on major themes involving European integration. These proposals would be submitted for examination by the European legislator if they fit in as part of the treaties in force.

From the European social model to the community budget, the debate over the Union's borders or the future of the common agricultural policy, a more frequent use of the conventional method would be an intelligent way of involving national parliaments which are far too often restricted to the role of censors in the construction of Europe. They would stand as a true means of proposal which are not disconnected from national public opinion.

3.2 The "Convergence" Method: a response to the Union's Enlargement

European public opinion is extremely skeptical about the EU's ability to manage the heterogeneity involved in the increase in the number of its Member States. Because of its non-binding nature the open method of coordination has demonstrated its limitations.

Like the mechanism that led to the creation of the Single Currency (and whose implementation loosened after its launch), indeed it appears opportune to extend the setting of convergence criteria to the main policies that come under the Union's competence according to the strict respect of the subsidiarity principle. Convergence must lead to the establishment of a direction so that European policies are clear; it must help towards restoring confidence between the European Union and its citizens.

We suggest the conclusion of a "European Convergence Pact" that will give rise to the adoption of sectoral convergence programmes drafted by the Commission which are based on both quantitative and qualitative goals (including those of a legislative nature) in areas as diverse as justice, security, taxation, social policy, research, etc. The "European Convergence Pact" would be a global framework shared by all Member States but within which participation in sectoral programmes could be undertaken starting with a small number of Member States. From a methodological point of view a prior assessment of the area in question would have to be made in order to pinpoint exactly the subjects in which the States could strengthen their cooperation, in other words undertake a joint policy.

The definition of convergence programmes should go hand in hand with the introduction of an implementation timetable and binding mechanisms that focus on an obligation of means rather than on an obligation of results (the important thing being that an adequate effort is made towards convergence, since results may be affected by exogenous and economic factors).

The convergence pact has the advantage of involving all the countries which belong to it, focusing on joint goals and a long term credible obligation of means. This new method of European governance, which might at first be experimented in the euro zone, could be achieved with the treaties as they stand.

3.3 The Method of Strategic Cooperation: a response to globalization

Although the Lisbon Treaty eased the conditions required, the use of the enhanced cooperation agreement is still extremely limited and only concerns one-off issues such as conjugal status or the Single European Patent.

But there are areas in which enhanced cooperation agreements – including areas that are not within the Union's competence – can prove to be strategic within a context of globalization, where new forms of cooperation need to be established. This is the case for example in the energy sector or in asylum and immigration policy.

The introduction of strategic cooperation agreements would involve both regalian as well as all other types of areas in which a strategic European interest can be pinpointed. These strategic cooperation agreements should enjoy the operational support, in as far as they require it, of the services of the EU's institutions.

Amongst the possible examples of strategic cooperation agreements we can quote defence, energy (with the creation of a "European Energy Community" [32]), innovation (in federations such as the United States and Canada, R&D spending are 90% funded on a federal level) or cooperation between universities (e.g. enabling the creation of European university clusters).

Strategic cooperation agreements should be able to accommodate both members and non-EU-members. In the energy sector for example, strategic cooperation of all or some of the EU countries with Norway and/or Russia may go towards promoting Europe's general interest.

These strategic cooperation agreements would be based on the pooling principle which is particularly pertinent in times of budgetary austerity in the Member States and should be supported by a new financial instrument – the Strategic European Fund, that follows along the same line as the European Structural Fund but this time it would be devoted to projects that area qualified as strategic, including only Member States which want to take part.

Every strategic cooperation agreement would be the focus of an ad hoc governance mode within the context of enhanced cooperation agreements or alternatively of inter-governmental treaties. In this case it would seem appropriate however and as far as possible, to find support in the resources and competences of the existing European institutions.

Conclusion

The crisis, which increases mistrust on the part of European citizens with regard to its institutions, and the reforms now underway place Europe before a major political challenge.

Either the leaders of Europe will show they can come to agreement over sufficient measures to respond to the criticisms that target its democratic and executive deficits - and thanks to this they will help the emergence of a European "demos" and provide sense to European citizenship -, or otherwise they run the risk of seeing Euro-skepticism gather strength as soon as steps are taken towards integration which do not go hand in hand with democratic control and an adequate decision-making capability. Many Europeans may fall back on their own national identity which they feel is the only guarantor of their political rights.

Facing this choice some politicians brandish the memory of the negative referenda against the draft European Constitution. But it is this very scenario that they are in danger of repeating if they do not enhance the political and democratic aspect of the European project. Indeed the approach comprising the transfer over to Europe of major economic competences (banking union, budgetary union, enhanced macro-economic supervision) without the transfer of the corresponding legitimacy will lead to rejection on the part of the citizens, many of whom will feel they are losing their power of decision. The new European powers would be seen by the latter as a technocratic, democratic edifice that eludes the citizens' influence. 2013 could very well be like 2005. The best way to avoid this would be to launch public debate over the real means to enhance the legitimacy of European decisions. It is time to stop postponing this debate to a future than never comes.

[1] Speech on the State of the Union 2012 to the European Parliament 12th September 2012.

[2] Die Ziet, 29th August 2012.

[3] Report presented to the European Council on 29th June 2012 – "Towards Genuine Economic and Monetary Union" http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/fr/ec/131278.pdf

[4] See Jean-François Jamet, L'Europe peut-elle se passer d'un gouvernement économique ?, La documentation française, 2011 ; 2nd edition (forthcoming). Or the report "Completing the Euro. A Road Map towards a Fiscal Union in Europe ", Report of Tomaso Padoa Schioppa Group, 2012 - http://www.notre-europe.eu/uploads/tx_publication/CompletingTheEuro_ReportPadoa-SchioppaGroup_NE_June2012.pdf

[5] As an example, cf. J. Janning, " Political Union: Europe's Defining Moment ", EPC Policy Brief, European Policy Centre, 2012 ; I. Pernice (et allii), "A Democratic Solution to the Crisis. Reform Model for a Democratically Based Economic and Financial Constitution for Europe", Walter Hallstein Institute for European Constitutional Law, Humboldt University Berlin, 2012; and M. P. Maduro., B. De Witte, M. Kumm, "The Euro Crisis and the Democratic Governance of the Euro : Legal and Political Issues of a Fiscal Crisis", Policy Report, Global Governance High-Level Seminar – "The Democratic Governance of the Euro, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, 2012.

[6] Cf. Final Report of the Future of Europe Group of the Foreign Ministers of Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Germany, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal and Spain, 17th September 2012 - http://www.msz.gov.pl/files/docs/komunikaty/20120918RAPORT/report.pdf

[7] European Council, Issues Paper on Completing the Economic and Monetary Union, 12th September 2012. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/132413.pdf

[8] Democratic legitimacy first results from the democratic definition of the political goals of the European institutions. It also supposes the democratic vote of the legislation that is necessary for the achievement of these goals. Finally it requires the democratic control of the implementation of this legislation. The democratic legitimacy of the European institutions can be direct or indirect.

[9] The question of strengthening democratic legitimacy is not just about responsibility and accountability; these are necessary but not sufficient components since they do not satisfy the demand of many citizens to participate in the the orientation of choices and decisions taken at Union level.

[10] Cf. T. Chopin "Europe and the Need to Decide : Is European Political Leadership Possible?" in the Schuman Report on Europe:State of the Union 2011, Lignes de repères, 2011 ; Nicolas Véron " The Political Redefinition of Europe ", Opening Remarks at the Financial Markets Committee (FMK)'s Conference on " The European Parliament and the Financial Market ", Stockholm, June 2012 and " Challenges of Europe's Fourfold Union ", Hearing before the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations : Subcommittee on European Affairs, on " The Future of the Eurozone : Outlook and Lessons ", August 2012 and Peter Ludlow, " Executive Power and Democratic Accountability ", Quarterly Commentary, Eurocomment, September 2012.

[11] Cf. Dominique Reynié, Populismes : la pente fatale, Paris, Plon, coll. " Tribune libre ", 2011.

[12] The expression "permissive consensus" was invented by Vladimer O. Jr., Key, Public Opinion and American Democracy. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1961, and was introduced for the first time regarding European integration by Lindberg and Scheingold in their assessment of the support of public opinion to European integration in Leon N., Lindberg and Stuart A., Scheingold, Europe's Would Be Polity. Patterns of Change in the European Community, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1991

[13] See for example Larry Siedentop, " A Crisis of Legitimacy ", in Prospect, 2005 ou J. Thomassen, " Citizens and the Legitimacy of the European Union ", The Hague, WWR Web publication, n° 19, 2007. www.wwr.nl see also T. Chopin, "La crise de légitimité de l'Union européenne", in Raison publique, Presses de la Sorbonne, n°7, 2007 and " The Limits of the Functionalist Method : Politicization as an Indispensable Mean to Settle the EU's Legitimacy Deficit", in Olaf Cramme (ed.), Rescuing the European project: EU legitimacy, governance, and internal security, London School of Economics – Policy Network – Eliamep, vol. 1, 2009.

[14] An inter-institutional agreement is an act adopted jointly by the EU's institutions in their area of competence by which these govern their means of cooperation or commit to respecting a set of rules. Inter-institutional agreements are born of the practical requirement of the institutions to specify certain measures in the treaties which concern them in order to prevent conflict and to adjust their respective competences. Originally they were not part of the treaties and were formally introduced with the Lisbon Treaty, in article 295 of TFEU.

[15] Except for the EPP-Liberal agreement in 1999 that introduced a partisan split within the European Parliament for the very first time.

[16] For more details refer to T. Chopin and L. Macek, " Après Lisbonne, le défi de la politisation de l'Union européenne ", in Les Etudes du CERI, n°165, Centre d'Etude et de Recherches Internationales, Sciences Po, 2010.

[17] Article 13 of the Treaty On Stability, Coordination And Governance In The Economic And Monetary Union anticipates that the "European Parliament and the national Parliaments of the Contracting Parties will together determine the organization and promotion of a conference of representatives of the relevant committees of the European Parliament and representatives of the relevant committees of national Parliaments in order to discuss budgetary policies and other issues covered by this Treaty."

[18] For an initial outline of the possible shape this assembly might take cf. Jean Arthuis, " Avenir de la zone euro : l'intégration politique ou le chaos ", in a Robert Schuman Foundation Note, n°49, March 2012.

[19] Another possibility would be to turn the Euro Zone Assembly into a European Parliament body limited to the MEPs of the euro zone. This solution would be simple but would not allow for the creation of a strong link with the national parliaments which enjoy major legitimacy in economic, notably budgetary areas. The proposal for a Euro Zone Assembly is not the focus of a consensus today and it is likely that the European Parliament would be against the idea of its creation since it would undoubtedly be deemed as a competing assembly.

[20] Created in 1989 the COSAC (Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairs of Parliaments of the European Union) is a cooperation body that brings together the committees from the national parliaments specialized in European affairs and the representatives of the European Parliament. During the COSAC's six-monthly meetings each of the parliaments is represented by six members. In virtue of article 10 of Protocol 1 on the role to be played by the national parliaments in the EU of the Lisbon Treaty, the COSAC "may submit any contribution it deems appropriate for the attention of the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission. The Conference shall in addition promote the exchange of information and best practice between national Parliaments and the European Parliament, including their special committees. It may also organize inter-parliamentary conferences on specific topics, in particular to debate matters of common foreign and security policy, including common security and defence policy. Contributions from the Conference shall not bind national Parliaments and shall not prejudge their positions."

[21] Monetary aggregates enable the monitoring of the quantity of liquidities (including money instruments and the most liquid financial assets) in an economy distinguishing between their various forms (coins, notes, bank deposits, loans etc.)

[22] Cf. T. Chopin andJ.-F. Jamet, "The distribution of seats in the European Parliament between the Member States : both a democratic and diplomatic issue", in Questions d'Europe – the Robert Schuman Fondation's Policy Papers, n°71, 2007.

[23] A simple solution would be to have an MP for X (for example 1) million inhabitants with a minimum of one or two MPs per Member State.

[24] The German Constitutional Court of Karlsruhe's decision on the Lisbon Treaty stresses that the democratic principle applied to a State means the respect of certain conditions that the Union does not fulfil, notably the fact that the European Elections are not undertaken according to the "one man one vote" principle. On this point we might refer to the discussion on Les conséquences du jugement de la cour constitutionnelle fédérale allemande sur le processus d'unification européenne, Robert Schuman Foundation / Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, September 2009 and also Hubert Haenel, "La Cour de Karlsruhe. Une leçon de démocratie", in Commentaire, n°130, summer 2010.

[25] Cf. Y. Bertoncini, Europe : le temps des fils fondateurs, Michalon, 2005.

[26] Cf. Speech by Jean-Claude Trichet, then President of the European Central Bank on the occasion of the award of the Charlemagne Prize 2011 in Aachen on 2nd June 2011.

[27] The measures adopted on the basis of article 136 are being put forward at present by the Commission and adopted by the Council and the European Parliament in co-decision.

[28] See the proposal that the European Commission presented on 10th September last: Towards a Banking Union, 10th September 2012 http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/12/656&format=HTML&aged=0&language=FR

[29] Applied to a regulation authority, the expression refers to the situation in which the administrations responsible for a subject internalise the logic specific to the sectors or professions they are regulating to the point of losing the required critical distance.

[30] The community method gives the European Commission the legislative initiative. The Commission drafts a proposal on the basis of a consultation with the Member States and civil society. This proposal is then examined by Parliament and the Council which co-decide. The Council can only amend it with a unanimous vote and expresses itself most often via a qualified majority.

[31] The inter-governmental method grants the coordination of Member States' political decisions to the Council alone without the participation of the Parliament. The unanimity of the Member States is required.

[32] On this point see Joachim Bitterllich, "Pour une Haute Autorité européenne de l'énergie ", in L'état de l'Union 2009. Rapport Schuman sur l'Europe, Lignes de repères, 2009 and also Sami Andoura, Leigh Hancher and Marc Van Der Woude, "Vers une Communauté européenne de l'énergie : un projet politique", Notre Europe - Etudes et Recherches, n. 76, July 2010.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :