Industry

François Lépine,

Marc Lavédrine

-

Available versions :

EN

François Lépine

Marc Lavédrine

Introduction

The transport sector, which is cross-border by nature, seems to lend itself particularly well to European integration. Moreover, this sector is a potential source of investment for growth and competitiveness which are especially necessary in this time of economic hardship for the European Union. It is within this context that on 19th October 2011 the European Commission submitted some ideas regarding the Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T), which are under discussion by the European Council and the European Parliament.

Here we offer an assessment of these ideas, what they entail and the changes they are to bring about. We shall then look at an emblematic example of investment for growth and competitiveness in the transport sector, i.e. the building of the new Lyon-Turin rail freight and passenger link. We shall end with some thoughts on the need for a European legal and financial framework that is adapted to this kind of large-scale infrastructure project.

1. Working towards the true revival of the Trans-European Networks Policy

This policy has come a long way. Indeed European Transport was supposed to comprise the third pillar of European integration on the entry into force of the Rome Treaty. However it was not until 1994 that it really took shape as the Trans-European Networks. These do not just involve transport but also the energy and digital networks [1]. It was then based on priority projects that were mainly new axes that had to be created involving a limited number of Member States. From an initial 14 these priority projects totalled 31 in 2001. In spite of some undeniable successes like the completion of the High Speed Links along which the Thalys runs or the Øresund bridge-tunnel between Sweden and Denmark, this policy has struggled because of two shortcomings:

• an adequate budget so that European funding comprises a decisive lever. Hence during negotiations of the last multi-annual financial framework 2007-2013, the Commission's 22 billion € proposal was reduced to 8 billion €. As a comparison, investment in infrastructures in France totalled 15.9 billion € in 2005 alone (source FNTP),

•a sufficiently binding framework so that Member States honour their commitments. Indeed many of these axes include cross-border sections for which there is less political motivation than for strictly national infrastructures.

The proposals made on 19th October 2011 mainly break with these ideas. Firstly they are part of a political vision:

•comprising a European budget, the motor of growth and employment for the European Union. Hence the Commission introduces a proposal for the Trans-European networks, comprising the "Connecting Europe Facility" and a 50 billion € budget covering the period 2014-2020 (31.7 of which for transport) and an initiative in support of Project Bonds for infrastructure funding. This budget that can be compared with the 8 billion of the ongoing period, would represent 10% of the total investments to be made on the core network by 2030;

•comprising a 60% reduction of transport emissions by 2050 and the development of a European economy that is as decarbonised as possible. Hence the core network is multimodal and privileges the railway and all other alternative modes of transport other than the road.

Secondly they introduce a true European network integrating both existing infrastructures – which are the most numerous – to be brought up to standard to enable an efficient transport system in Europe, as well as new infrastructures that have to be created, thereby enabling the effective connection of 83 urban centres, 37 airports and 83 ports in the European Union. This so-called core network should be operational by 2030. A second deployment phase by 2050 should enable most European citizens to be within 30 minutes of the core network.

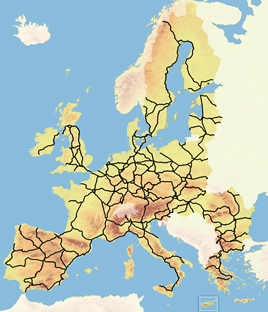

The map of the trans-European network proposed by the Commission (October 2011)

The map of the trans-European network proposed by the Commission (October 2011)

Finally they strengthen the European Union's coordination capability for the effective implementation of this core network. Notably 10 main corridors structuring the network will be placed under the management of European coordinators who will enjoy greater powers. Moreover European funding will be brought up to 40% for the completion of cross-border sections, which are the most difficult to undertake for political and also for geographical reasons (mountains, stretches of sea etc ...).

2. The Lyon-Turin link: an example of investment for growth and competitiveness.

Presentation and goals

The Lyon-Turin rail link [2] aims to create a modern line between France and Italy so that there is an efficient connection both for freight and passengers. This axis is the key element both for east-west traffic between Spain, the south of France, Italy and south east Europe and also between the UK, Benelux, the north of France and Italy. This axis is served by a railway line that dates back to 1871. Heavy freight trains have to climb to altitudes of 1300m, whilst the same trains run at 800m in Switzerland in the Lötschberg tunnel; very soon they will run at 550m in the future Saint-Gotthard tunnel. It also forces passenger trains to travel at 60km/h as they cross the Alps, placing Milan at 7 hours by TGV (in comparison the high speed train from Paris, takes 3 hours to reach Marseille which is just as far away: 800km!

The new Lyon-Turin rail link is one that is mainly designed for freight. The development of rail freight is a policy initiated by the European Union and which has been successful. With a 10% rise in the volumes transported over the last decade, rail freight has declined in most European countries. France which is still an exception in this area, will soon fall in line with the continental trend, unless it wants to revive its industry, since this mode of transport is largely adapted to industrial requirements. At present 85% of trade across the Franco-Italian border passes via the road, whilst only 65% passes across the Italian-Austrian border and 35% in Switzerland. The Lyon-Turin link aims to change this modal share. It will also enable the development of a high speed passenger link in Europe, offering a credible alternative to short distance flights. With these goals the Lyon-Turin links directly matches the European Union's aim to "decarbonise" the economy.

The Lyon-Turin link includes three elements:

•The so-called base tunnel linking Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne to Susa is the decisive component because it offers a flat route tunnel under the mountain at an altitude below 600m. The investment necessary for its completion totals 8.7 billion €, 8. 2 for works. It will enable the efficient use of freight trains and one hour less journey time for rail passengers. The preparatory work started several years ago and 800 million € have been committed, with European funding totalling nearly 50%.

• Access in France enables links between Lyon-Chambéry to Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne ie 140 km of mixed freight/passenger links – partly devoted to freight.

• Access in Italy will enable the link between Susa and Turin, i.e. 60km of mixed freight/passenger links.

The latter part, which concerns Italy, was the focus of strong opposition as of 2005. A widespread consultation procedure was launched under the aegis of Mario Virano, the extraordinary Commissioner for this link. Discussions ended during summer of 2011 with a new trajectory that was approved by most of the communities involved and also by the Italian government. At the same time preparatory work started on the Italian side. In March 2012 Mario Monti, the President of the Italian Council chose to turn the Lyon-Turin link (or rather the Turin-Lyon link, as seen from Rome), into a marker as part of his policy based on budgetary austerity linked to investments for competitiveness and growth.

A potential growth factor for France, Italy and all of Southern Europe

The most recent cost-benefits analysis presented in Rome on 26th April 2012 highlights a 5% profit rate of the entire link between Lyon and Turin, in other words a net present value of between 12 to 14 billion € after 50 years. The first to gain from this link will be businesses, notably industrial companies which will benefit from the improved efficacy and reduced rail transport costs on mid to long distance journeys.

As soon as work starts the positive effects on growth will be significant. The completion of the base tunnel alone in the Alps will generate between 6,000 to 10,000 jobs, both directly and indirectly, over the coming ten years. Given the spread of this investment between the EU, Italy and France, positive effects will be achieved in optimal financial conditions.

The impact of this new link goes beyond the strict Franco-Italian framework because it is in fact a "revolution" for transport in the south of Europe, comparable to the Channel Tunnel – and Thalys for North West Europe.

The Lyon-Turin rail line is the strategic element at the centre of the Mediterranean corridor (corridor No.3), which connects up the major economic, industrial areas of southern Europe with each other and with the rest of the continent: the Spanish economic axes of Catalonia, South East France, notably Rhône-Alpes, its second most important industrial region, the North of Italy, Europe's second most important industrial basin (which alone represents 7% of the Union's GDP). In all 200 billion € in annual trade are directly involved in this link.

One of the features of the economy in the Northern Europe is that it enjoys an extremely dense, high quality transport network. We simply have to look at the map to gauge this. If the whole of the Union wants to recover a sustainable growth path, it is vital for the south to have comparable advantages. By saving time and enabling better performance the Lyon-Turin rail link is decisive in terms of transport of merchandise as well as passengers.

3. The Need for an Adapted European Legal and Financial Framework

Although it is a flagship project in the TEN-T policy, the base tunnel in the Lyon-Turin link is nevertheless an "exceptional" project due to its scale. In the discussions over the financial regulation of the TEN-T in 2007 the idea of the large scale project came to the fore. It is now time to draw up an adapted legal framework for their completion.

Large scale projects stand apart from infrastructure projects because of two features: they represent major investments (several billion €) and they are not phasable: the expected benefits are linked to the completion of the entire investment.

When there is a new flat rail link or a motorway each section that is completed provides improvements. Hence the lines on which the Thalys runs were brought into operation progressively: first Paris-Lille, then Lille-Brussels, then Brussels-Amsterdam. Hence the project can be phased and potentially, budgetary constraints can be introduced.

In the case of a tunnel under the Alps, like the Mont-Cenis (Moncenisio) tunnel in the Lyon-Turin link, a "lump" investment of 8 billion € is necessary. There are some other, similar major European projects: the Brenner Tunnel between Austria and Italy (6.4 billion €) or the Fehmarn Belt fixed link between Denmark and Germany (5.1 billion €).

In return these large scale projects provide just as exceptional benefits in the sense that they "change geography" as was the case with the Channel Tunnel at the end of the last century.

The legal framework put forward by the European Commission has to take these specific elements on board otherwise it will be ineffective in the achievement of vital infrastructures. Two main problems prevail: the Member States' commitment that is not the same as that of the European Union and the time limits of the multi-annual financial framework.

The funding rule of TEN-T infrastructures is that the States involved, generally two in the case of cross-border sections, commit to the project's completion, including from a financial point of view, then they turn to the Commission for a subsidy. But if this subsidy totals 40% of an investment of over 8 billion €, i.e. more than 3 billion, we understand that the procedure leads to a vicious circle. The States wait for the subsidy before committing themselves and the Commission waits on the States' commitment to set the amount of the subsidy. Given the amounts involved it would be better to adopt a type of "closing" procedure in which each commits to provide the necessary resources for the completion of the investment at the same time. In his report to the Regions Committee on the new TEN-T policy Bernard Soulage, Deputy Chairman of the Rhône-Alpes region suggests the implementation of tri-partite contract programmes for the completion of cross-border sections, which jointly commit the two States and the European Union. This kind of solution is also planned for in the future regional policy in the shape of partnership contracts within which the regions, States and the EU would jointly commit. It is most certainly one solution.

The other difficulty to overcome is that of timing. The Union's financial commitment is limited to the seven years of the multi-annual financial framework (MFF). However these large scale projects take more than ten years to complete. In the case of the Lyon-Turin link the project is due to start in 2014 and come to an end between 2013 and 2025, i.e. the time of two financial frameworks. Likewise it is difficult to make an investment if the financial commitment of one of three main players does not cover the entire duration of the operation. As part of the present process the funding rate and corresponding sums provided by the EU are only guaranteed until 2020 i.e. 2/3 of the operation more or less. This uncertainty weighs one billion € however. It seems necessary to plan for the tripartite contract committing the EU beyond the MFF, until the operation has been completed.

These modifications to the legal framework of the TEN-T could be integrated during the on-going discussions both within the Council and the European Parliament. They are necessary to the corridors involved in these large scale projects. They are also necessary for all of the TEN-T policy which has to be able to use flagship projects as support where European added value is obvious. Only these large scale projects, and singularly, the base tunnel in the Lyon-Turin link, are likely to provide this.

In addition to these changes the approval of the Commission's proposals is vital. More specifically the 50 billion € budget allocated to the Connecting Europe Facility. The growth policy sought after by both the Union and the Member States is undoubtedly part of this initiative. Italy now wants this budget to be increased. If this is true and if the European "Project Bonds" become a reality no one doubts that the development of sustainable infrastructures will be possible in Europe over the next ten years. These will provide a decisive contribution to growth and employment in the EU and to its transition towards the post-carbon economy. The Lyon-Turn rail link is an integral part of this logic.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :