Institutions

Eric Maurice

-

Available versions :

EN

Eric Maurice

On 9 May after a year's work the Conference on the future of Europe delivered its conclusions to chart the way for a "new, effective and more democratic Europe (...) sovereign and capable of acting", to quote one of its co-chairs, Guy Verhofstadt (BE, Renew).

The Conference, which was an unprecedented exercise in participatory democracy at EU level, involving citizens, experts, representatives of the institutions and politicians, will only have achieved its objective if Europe, and in particular its Member States, follow and appropriate at least part of its recommendations. A first discussion is taking place at the European Council on 23 and 24 June, whilst the Parliament has already expressed its position and expectations.

While a debate on the timeliness of revising the treaties was quickly launched around a few strong measures such as the abolition of unanimity when taking certain decisions, the questions raised by the Conference mainly concern the content and purpose of European policies and the participation of citizens in the definition and development of these policies. Initiated before the Covid-19 pandemic, launched and conducted between different phases of health restrictions, and concluded in the midst of the war in Ukraine, the Conference is both a review of the European project at a time of profound change as well as a call for its renewal. It is therefore fitting to examine its proposals and the possibilities of their implementation.

The Conference on the Future of Europe was suggested in March 2019 by French President Emmanuel Macron in his letter to Europeans, to "to propose all the changes our political project needs, with an open mind, even to amending the treaties". The idea was taken up by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, with the support of the Parliament. Delayed by lengthy discussions between institutions on its functioning, and then by the pandemic, the Conference opened on 9 May 2021 under the joint presidency of the Parliament, the Commission and the Council.

In a joint declaration, the presidents of the three institutions stressed that this was a "citizens-focused, bottom-up exercise" exercise and pledged to "listen to Europeans and follow up the recommendations made during the Conference". By including citizens in a broad institutional debate, the European Union has aimed to strengthen its democratic legitimacy and reinforce the link between the institutions and citizens. The Conference was based on the principles of inclusion, openness and transparency, and on the respect for European values. This complex mechanism was designed to cross perspectives by multiplying scales and actors.

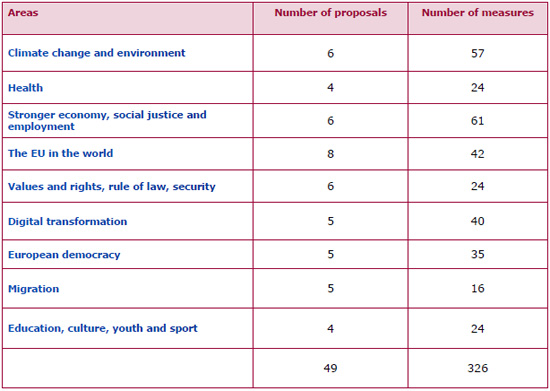

A total of 6,465 events were organised in the 27 Member States, with 652,532 participants. An online platform in all official languages registered five million visitors, with 52 346 active participants sharing 17,671 ideas and leaving 21,877 comments. National citizens' panels were held in six countries: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Lithuania and the Netherlands. Four thematic panels, comprising 200 randomly selected Europeans, were organised and produced 178 recommendations. These were assessed and synthesised by the Conference plenary assembly, which was made up equally of representatives of the three institutions and representatives of national parliaments, as well as citizens and representatives of the social partners and civil society. This final report was drafted by an Executive Board of nine representatives from the Parliament, the Commission and the Council, in collaboration with the Conference plenary. In total, the Conference conclusions contain more than 320 measures divided into 49 proposals on nine main topics.

The distribution of the proposals of the Conference on the Future of Europe

A plan for an ideal Europe

Through their proposals, the participants in the Conference have outlined a project for a Europe that would be more ecological, social and democratic, intervening more directly in daily life and in national political frameworks. The measures proposed are, for the most part, in line with the priorities already expressed or implemented by the Union, but they go further. "The EU needs to be more than an economic union. Member States need to show more solidarity towards one another. We are a family and should behave as such in situations of crisis", say the citizens' representatives, who believe that the Union "needs to be bold and act fast to become an environment and climate leader".

This ambition is reflected in particular in the demand for greater political and financial investment to reduce dependence on oil and gas imports, including through the consideration of "geopolitical and security implications, including human rights, ecological aspect and good governance and rule of law, of all third country energy suppliers," (proposal 3.2), and to develop more sustainable and accessible European and local transport networks. It is also reflected in collective objectives such as common minimum health standards at European level (proposal 10.1) or the promotion of employment and social mobility to allow people "to have a full chance of self-realisation and self-determination" (proposal 13.9). This ambition is also reflected in the proposals to strengthen the European data protection model (proposal 26) or to step up the combat against disinformation, including through a "review of the media business model" to ensure their integrity and independence (proposal 27.1).

In this quest for an ideal Europe, the Conference has therefore not hesitated to call for a more dirigiste Union, which would, for example, introduce "coercion and reward system to tackle pollution applying the polluter pays principle" (proposal 2.2) or reduce subsidies to "agricultural mass production" and redirect them towards "environmentally sustainable agriculture" (proposition 30.3). Delegates also requested the European Union "not to compromise on welfare rights (public health, public education, labour policies)" (proposal 14.2), and make it "mandatory for children to reach competence in an active EU language other than their own to the highest possible level." (proposal 48.2). It would also like the European Union to take steps to "to guarantee that all families enjoy equal family rights in all Member States", including the right to marriage and adoption for all (proposal 15.5).

While the proposed measures as a whole tend towards an increased Europeanisation of policies and means of action, they also reflect a demand for regulation that is surprising in view of the criticism traditionally levelled at the Union, moving away from the "big on big things, small on small things" initiated by the Commission. The Conference also hopes to see the European Union "promote a plant-based diet on the grounds of climate protection and the preservation of the environment" (proposal 6.8), "develop at EU level a standard educational programme on healthy lifestyles" (proposal 9.2), and to protect pedestrians and cyclists by "guaranteeing road safety and by providing training on road traffic rules" (proposal 4.7).

Strengthening competences and institutions

The vast majority of the Conference's proposals, particularly in the fields of the environment and energy, digital technology, the economy and social affairs, correspond to a deepening of existing policies, so as to increase their scope or accelerate their effects. However, the participants in the Conference recommended deepening Community integration in areas identified as important in tackling the current crises or strengthening Europeans' sense of belonging. This is the case for health, the environment, education and foreign policy. This deeper integration would be achieved either by extending the European Union's competences or by strengthening its institutions and agencies.

For example, the Conference calls for "health and health care" to be included among the competences shared between the European Union and its Member States, "in order to achieve the necessary coordinated, long-term action at Union level" (proposal 8.3).

As noted during the COVID-19 pandemic, to date the European Union has only enjoyed a supporting competence[1] in terms of public health and shared competence in a limited number of areas, such as the improvement of public health, the prevention of diseases and physical health hazards, the fight against "major health scourges" and the monitoring of serious cross-border threats to health[2].

The Conference proposes the establishment of new shared competences in the field of education, which is currently only a supporting competence, with a view to enabling the creation by 2025 of "an inclusive European education area within which all citizens have equal access to education". Participants requested this change "at a minimum in the field of citizenship education" (proposal 46.1), including climate change and environmental education (proposal 6.7), and data protection (proposal 26.3). This extension of Community competence would lead to increased cooperation on national, regional and local school programmes. The implementation of these new competences would imply the modification of article 4 TFEU, which specifies the areas concerned. Similarly, it proposes strengthening the EU's competences in the field of social policies (proposal 14.1) as a way of moving towards 'full' implementation of the European Social Rights Framework adopted in 2017.

For the Conference participants, the strengthening of the Community institutions is a corollary of the enlargement of the European Union's competences. One of the most important proposals is to give the Parliament a right of legislative initiative (proposal 38.4), and the right to "decide" the budget like national parliaments do (proposal 38.4). This last proposal, which would allow the Parliament to amend the Multiannual Financial Framework and not just approve or reject it as is currently the case, is contested by the Council, which considers that it does not emanate from the citizens, and the members of the citizens' panels, who point out that they have not had enough time to study it - implying that it has been introduced by the Parliament.

As a logical consequence of the increased communitarisation of policies reflected in these proposals, the end of unanimity voting in the Council is one of the other strong measures recommended by the Conference. Delegates believe that "All issues decided by way of unanimity should be decided by way of a qualified majority[3]", allowing decisions on the accession of new States or on the modification of fundamental principles to be the "only exceptions" (proposal 39.1). In particular, they mention the common foreign and security policy (proposal 21.1) and fiscal policy (proposal 16.1). Without giving further details, they suggest that qualified majority voting should be used for decisions on "themes identified as being of 'European interest', such as environment".

More involvement on the part of the citizens

The Conference, which was designed as the most ambitious exercise in involving citizens in the definition of future European policies, resulted in a series of proposals to strengthen the role of citizens in decision-making. It even proposed the establishment of a European Charter for citizen contribution to European affairs, based on its recommendations (proposal 36.11). In view of creating "a full civic experience" for Europeans, the Conference proposes three types of measures: for better involvement in the decision making and life of the institutions; for greater mobilisation; for institutions that are closer to the people.

A first proposal is to give citizens a greater role in the choice of the President of the Commission, either through direct election or through the continuation of the system of lead candidates (spitzenkandidaten), whereby the candidate of the leading party in the elections is appointed by the European Council and then elected by the Parliament (proposal 38.4). Implemented in 2014 with the election of the European People's Party (EPP) candidate Jean-Claude Juncker, this system was challenged in 2019 by the European Council, which rejected Manfred Weber (DE, EPP) and proposed Ursula von der Leyen to the Parliament's vote. It is still a strong claim made by Parliament.

The Conference also proposes a direct vote by citizens in referendums to be held in the European Union, "to be triggered by the European Parliament, in exceptional cases on matters particularly important to all European citizens". (proposal 38.2). However, such referendums should only be held in "exceptional circumstances" due to their cost.

Upstream of the decision-making process, the Conference suggests, without going into detail, strengthening cooperation between legislators and civil society organisations (proposal 36.10). It also recommends the establishment of citizens' assemblies drawn by lot based on representativeness (proposal 36.7). Established on a legally binding basis, they would be held every twelve to eighteen months with the participation of experts and could issue recommendations which the institutions would be obliged to follow, unless they could justify not doing so.

More generally, the Conference suggests that citizens' participation processes should take place in association with civil society organisations, regional and local authorities, and EU bodies such as the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of regions (proposal 36.5). It also suggests a "Youth-check" of legislation if this is likely "to have an impact on them" (proposal 36.9), which would involve an impact assessment and a consultation mechanism with young people's representatives. As with most of the proposals, few details are provided on the modalities of implementation or their content, which are more of a suggestion than a concrete proposal.

In addition, the Conference suggests measures to strengthen the exercise of democracy at European level and to increase the mobilisation of citizens in European elections and, more broadly, in debates on the Union's policies. It believes that granting the right to vote at 16 years of age in European elections "should be discussed and considered" (proposal 47.2). The challenge lies in harmonising national legislation across the Union, since the voting age for European elections has already been lowered to 16 in Austria, Malta and Belgium, and to 17 in Greece.

The Conference would like to see "some MEPs elected through a European Union-wide list" (proposal 38.3). This proposal, which takes up long-standing discussions between European parties, is in the process of being integrated since the Parliament adopted on 3 May draft legislative act which provides for the election of 28 MEPs in a new EU-wide constituency. The draft now has to be unanimously approved by the Council and then formally adopted by MEPs and Member States. A final set of proposals aims to help citizens to feel more European and to know the Union better. This would be based on the strengthening of 'Europe Houses' and other EU contact points at local level, or the creation of local EU advisors (proposal 36.6). As a continuation of the Conference's work, delegates suggested the creation of a "user-friendly digital platform" on which citizens could "share ideas, put forward questions to the representatives of EU institutions and express their views on important EU matters and legislative proposals". (proposal 36.3).

In a more original way, there is a proposal to create an EU fund that would encourage online and offline interaction, such as exchange programmes, panels or meetings, competitions, of varying duration between EU citizens (proposal 37.6). The proposal does not, however, specify the themes that could be covered by the fund.

Measures applicable to the treaties as they stand

In a first analysis in the conclusions of the Conference on 17 June, the European Commission divided measures that could be taken in response to the Conference into four categories: existing initiatives that take account of the proposals, such as the European climate law; those already proposed and currently being discussed by the Council and Parliament, such as the new migration pact; planned actions that may take account of the reflections of the Conference, such as legislation on media freedom; and new initiatives or areas of work inspired by the proposals, which fall within the competence of the Commission, such as mental health issues.

Many of the recommendations made by conference participants can be implemented without treaty reform. For example, many of the measures proposed to combat global warming and protect the environment, or concerning external policy, do not require treaty reform, but changes in policy line or the deepening of certain policies. "There is already a lot we can do without delay," promised the Commission President on 9 May. However, this requires a shared political will between the Member States, the Commission and the Parliament. Some proposals which involve areas in which the treaties are vague could be implemented via the establishment of what can be called "constitutional convention" which would bring new practices into the political and institutional functioning of the Union. This is the case of the Spitzenkandidat system (proposal 38.4), which already stems from a wide interpretation of article 17.7 of the TEU. This could also be the case for a shift "towards voting for Union-wide lists, or 'transnational lists'" (proposal 38.3), if candidates in the European elections campaigned more, or even exclusively based on their membership of a European party rather than a national party. The Conference's key proposal is that the general changeover to qualified majority voting in the Council can be carried out without opening a procedure for the revision of the Treaties. It is in fact possible through the so-called passerelle clauses provided for in article 48.7 TEU, which allows for the introduction of qualified majority voting "in a given area or case". This procedure is not without its difficulties, however, as the abandonment of unanimity in the Council must be decided unanimously in the European Council and submitted to the national parliaments. In a resolution adopted on 9 June, the Parliament proposes to circumvent this obstacle by establishing the adoption of passerelle clauses by qualified majority instead of unanimity.

A necessary revision of the treaties

In addition to the extension of the Union's competences in the fields of health, education and climate, a certain number of the measures proposed, particularly in the field of European democracy, require a revision of the treaties, the extent of which will depend on the political choices of Europe's leaders.

This applies to the establishment of a European referendum (proposal 38.2), the direct election of the President of the Commission, the granting of the right of legislative initiative to the Parliament (proposal 38.4); the revision of the mechanism for the examination of legislative proposals by national parliaments and the possibility for them to propose European legislative initiatives (proposal 40.2). The proposal (39.3) to rename the Commission as the "Executive Commission of the Union" and the Council as the "Senate of the Union" could not be done without changing the treaties.

Other proposals, imprecise as they stand, may also require a revision of the treaties depending on how they are implemented. This is true of the idea of "giving further consideration to common borrowing at EU level" (proposal 16. 5), if it means maintaining the achievements made in 2020 during the pandemic with the €750 billion European recovery plan. This is also true of proposal 23.1, which provides for "joint armed forces that shall be used for self-defence purposes and preclude aggressive military action of any kind". The longer-term objective of electing the Parliament from purely pan-European or transnational lists would require changes to the Treaty on European Union, which specifies the number of elected members per Member State.

Requests by parliament

Although it concerns only a minority of the measures recommended by the Conference, the revision of the treaties is the most debated issue because it is the most cumbersome in institutional terms and the most perilous from a political standpoint. Traditionally in favour of developing the Union's primary law to further Community integration and strengthen the powers of the institutions, particularly its own, Parliament has already asked the European Council to initiate a revision procedure via the call for a convention.

The Convention, comprising representatives of the national parliaments, the Heads of State or Government of the Member States, the Parliament and the Commission, is provided for by article 48 TEU as part of the ordinary revision procedure. It examines draft amendments that aim to "to increase or reduce the competences conferred on the Union in the Treaties" and adopts by consensus a recommendation to a Conference of Representatives of the Member States. This conference must, in turn, agree on the amendments to the Treaties, which must then be ratified by all Member States.

Another procedure exists, called simplified revision, which only involves amendments to Part Three of the TFEU regarding "Union policies and internal actions" The European Council takes a unanimous decision which is then ratified by the Member States. This procedure may be necessary depending on the extent of the decisions taken to implement the Conference's recommendations, particularly in the fields of environment, energy, transport and economic and social policies.

In its resolution to the European Council, the Parliament lists the changes it would like to see introduced into the treaties, in addition to granting itself the right of initiative and full co-decision on the budget, it wants to "adapt" the Union's competences, "especially in the areas of health and cross-border health threats, in the completion of the energy union based on energy efficiency and renewable energies (...), in defence and in social and economic policies". It is calling for the European Social Rights Base to be "fully implemented" and for social progress to be integrated in article 9 TFEU which sets out the social requirements of the European Union. It proposes to introduce into the Treaties references to strengthening the Union's competitiveness and resilience, and to supporting investment in the "just, green and digital" transitions. It is calling for revised treaties to strengthen the procedure to protect the values of the European Union and to specify "the determination and consequences of breaches of fundamental values".

Reticent Member States

The heads of the other two institutions have adopted a more cautious position. The President of the Commission, who will present her proposals in September at the State of the Union speech, has committed to follow up on the Conference's work "either by using the full limits of what we can do within the Treaties, or, yes, by changing the Treaties if need be", while recalling how her institution has responded to recent crises "with the powers that already exist".

French President Emmanuel Macron, whose country is chairing the Council until 30 June, has said he supports the opening of a convention, while noting that it will be necessary to "define our objectives very clearly because you have to start a convention knowing where you are going".

The revision of the treaties, whether ordinary or simplified, and the activation of the passerelle clauses, are only possible if the Member States in the Council and their respective parliaments are unanimous. However, thirteen Member States[4] have warned in a joint document, that they are against amendments that are "unconsidered and premature" which might "drawing political energy away" from real issues such as the quest for solutions in response to the citizens and the management of geopolitical challenges that Europe is now facing. Among these thirteen reluctant countries are the Czech Republic and Sweden, which will successively be presiding over the Council from 1 July until 30 June 2023 and would, in this capacity, be responsible for leading the work on revising the treaties. Conversely, six Member States[5] have declared themselves "in principle open to necessary treaty changes that are jointly defined".

The European Union could therefore move towards a targeted and strictly controlled revision of the treaties, while examining which features amongst the 326 measures that have been put forward can be implemented without engaging in lengthy institutional discussions. However, intense debate between the Member States and between the co-legislators, Council and Parliament can be expected regarding whether the treaty changes requested by each of them are indispensable.

Meeting expectations

Beyond the thorny question of the scope of the revision of the treaties, the institutions and the Member States should agree on a set of measures likely to fulfill a more or less significant part of the Conference's proposals. On the one hand, because the legitimacy of future decisions will be strengthened if they are based on the requests made by the citizens; on the other hand, because these requests largely converge with the plans of European leaders. A study by the Parliament's research department, estimates that 37 of the 49 proposals converge partially or significantly with the priorities identified by the European Council. Convergence has increased significantly since the pandemic and the war in Ukraine has prompted the European Union to accelerate the dual transition from climate change to digital technology, while developing new strategies in the areas of health, industry and economic convergence.

The long-term outcome of the Conference will depend on the responses that are given and whether they are in line with the priorities expressed by the citizens. The war in Ukraine, started by Russia on 24 February 2022, just as the last citizens' panel was finishing its work, has changed European citizens' perceptions. A Eurobarometer survey published on 15 June shows that defence and security have become the main priority in 2022 for 34% of respondents, although the issue is not well developed in the Conference conclusions. But the following priorities, the EU's autonomy in energy supply (26%), managing the economic situation (24%), environment and climate change (22%) and unemployment (21%), are widely expressed in the Conference proposals.

In its analysis on 17 June, the Commission warns against any type of "re-interpretation or selection" of the proposed measures but does not commit itself to the direction to be taken. To ensure continued support from citizens, it plans a "conference feedback event" in the autumn. This gives Member States time to consider what new features they would be prepared to accept.

[1] This means that the European Union cannot legislate but can support, coordinate or complement the action of the Member States.

[2] Article 168 TFEU.

[3] A text can only be adopted in the Council if it gets the votes of at least 55% of the Member States (i.e. 15 out of 27), representing at least 65% of the Union's population.

[4] Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden.

[5] Germany, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :