Africa and the Middle East

Louis Caudron

-

Available versions :

EN

Louis Caudron

Former Deputy Director of Rural Development at the French Ministry of Cooperation

Public development assistance in 2018

In 2018, the OECD's Development Assistance Committee (DAC) estimated Official Development Assistance (ODA) at $153 billion. Excluding the decline in spending on refugees, which donor countries are allowed to count as ODA, the amount is stable compared to the previous year.

The five largest donors are the United States ($35 billion), Germany ($25 billion), the United Kingdom ($19 billion), Japan ($14 billion) and France ($12 billion). More than half of Official Development Assistance is provided by the European Union and its Member States.

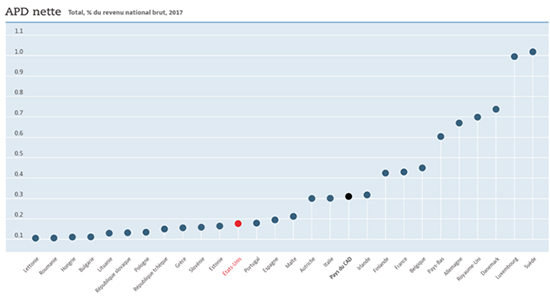

The $153 billion represents 0.31% of the donor countries' Gross National Income. This is a very different from the 0.70% target that all of these countries have pledged to reach. Five countries are on track however: Sweden (1.04%), Luxembourg (0.98%), Norway (0.94%), Denmark (0.72%) and the United Kingdom (0.70%). The United States is at 0.17%, Japan at 0.28%, France at 0.43% and Germany at 0.61%.

The accuracy of the DAC estimates should delude us. On the one hand, the inclusion in ODA of spending by donor countries on refugees is questionable. On the other, important donors such as Turkey or the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are not DAC members and are not therefore included in total ODA. Nonetheless, ODA, as tracked by the OECD since its inception, is a good indicator of the efforts made by donor countries in favour of developing countries.

Source : OECD

History of ODA

The idea of Official Development Assistance dates back to the late 1950s. It was introduced concurrently with the former colonies' independence. It was a time of the Cold War and the Western powers wanted to maintain links with the newly independent countries. In France, General de Gaulle saw the ODA as a means to maintain links and a certain influence over the former colonies. By changing their names, he maintained existing instruments to manage the latter. The Caisse Centrale de la France d'Outre-Mer, which had been the colonies' bank since 1944, became the Caisse Centrale de Coopération Economique (it still exists and is now called the Agence Française de Développement). The CFA franc, franc des Colonies Françaises d'Afrique, was retained, but the meaning of its name was skilfully changed. It became the franc of the Financial Community of Africa in West Africa and the franc of the Financial Cooperation of Africa in Central Africa. Note that in 2020, it will be replaced by the ECO. A Cooperation Assistance Fund (CAF) was created to provide grants and finance technical assistance to "in the field", developing countries, i.e. the former French colonies.

ODA was largely inspired by the Marshall Plan in Europe. Hence theoretical thinking on development assigned an active role to international aid, emphasizing the need to accelerate investment to support growth and, therefore, the need to provide external financing, since savings in developing countries were insufficient to finance investment at the desirable level. Aid donor countries considered that they had a strong interest in the development of recipient countries and thus became more attractive economic partners. Many officials believed that successes in Europe could be replicated everywhere, especially in Africa.

In addition to these political and economic concerns, particularly under the influence of the Scandinavian countries, there was a moral concern: the rich countries of the North had a moral duty to help the poor countries of the South.

France, a former colonial power with extensive experience in Africa, succeeded in convincing the newly created European Economic Community, of the interest of this policy. The European Development Fund (EDF) was set up in 1959 and, for more than twenty years, the EEC's Development Directorate was run by French nationals, often former administrators of France's Overseas territories/departments.

During the 1960s, African countries received between $20 and $30 billion in aid per year, which represented on average 0.45% of the donor countries' Gross National Income. As early as 1970, the United Nations General Assembly recommended that all developed countries devote 0.70% of their Gross National Income to Official Development Assistance. This injunction was not followed up, as ODA only represented 0.32% of the donors' GNI in the 1970s. This ratio even fell to 0.22% of GNI in the 1990s, after the break-up of the USSR, which ended the Cold War and removed a political justification for ODA.

From that time on, some economists began to question this policy's effectiveness. Their voices went unheard and, after the adoption in 2000 by the United Nations General Assembly of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the first International Conference on Financing for Development, held in 2002 in Monterrey, Mexico, strongly reminded donors of the objective of devoting 0.70% of their Gross National Income to developing countries.

This recommendation was not followed any more than that of 1970 and the ODA ratio remained around 0.30% in the years 2000/2010. At this level, in constant dollars, ODA in the years 2010 was three times that of the 1960s.

In a bid to improve aid effectiveness, donors adopted the Paris Declaration in 2003, which defined the following five principles:

• Ownership: Partner countries should exercise effective ownership of their development policies and strategies and coordinate action in support of development;

• Alignment: Donors should base all their support on partner countries' national development strategies, institutions and procedures;

• Harmonization: Donors' actions should be better harmonized and more transparent, and lead to greater collective effectiveness;

• Managing for results: Managing resources and improving decision-making processes to achieve results;

• Mutual accountability: Donors and partner countries should be accountable for development results.

Once again these requirements were barely met. Donor countries have been reluctant to consult each other and, in general, development assistance policy is judged by the means devoted to it rather than by the results it achieves.

The effectiveness of public development assistance

The effectiveness of ODA was quickly questioned. As early as 1962, the agronomist René Dumont alerted African governments to the fact. In his book L'Afrique noire est mal partie, he suggests that they should develop by themselves rather than behave like Europe's clients.

In 1988, economist Jean-François Gabas published L'aide contre le développement[1]. In 2001, in The Elusive Quest for Growth[2], American economist William Easterly considered that ODA, by transferring money to incapable and corrupt governments, does more harm than good.

The most direct attack came in 2009 from an African economist, Dambisa Moyo, who in her book Dead Aid[3] maintained that ODA is not only inefficient, but harmful, as it allows recipient governments to delay necessary policies.

In the field, ODA-financed projects have been greatly criticised: the choice of expensive equipment unsuited to requirements, the construction of infrastructures that quickly disappear due to lack of maintenance, and the amount of funding taken up by project structures or design offices. In some countries, government policy is in contradiction with ODA-financed projects. Countries such as Senegal or Cameroon choose to import cheap rice from Thailand or other Asian countries to the detriment of ODA-funded rice production projects in their own countries.

Africa, which has received a large share of ODA, does not compare favourably with Asia. In the 1960s countries such as Côte d'Ivoire or Senegal were at about the same level as Korea or Thailand. Sixty years later, African countries receiving ODA no lag significantly behind compared to Asian countries. In general, poverty has declined everywhere in the world except in Africa, the main ODA recipient.

It would be rather illusory to believe that ODA can bring about development, as it is only a minor element in the development process. According to the World Bank, remittances sent by migrants and diasporas to their countries of origin are expected to reach $550 billion in 2019. They will exceed the foreign direct investment (FDI) made in developing countries, which will be to the order of $520 billion. The $150 billion in ODA therefore represents only a very small proportion of the external money arriving in developing countries.

Moreover, the concept of ODA has been overturned by China, which has been strongly committed to Africa since 2000, but which does not do so out of generosity. It only supports projects that are likely to benefit both partners. It has thus financed a lot of infrastructures in exchange for raw materials. But its action has proved more effective than ODA in changing Africa's image and highlighting its potential.

Development aid policy in 2019

Curiously enough, the lack of ODA results has not changed its positive image among European policy-makers. At a time when European countries fear an influx of immigrants from Africa, many politicians even call regularly for the launch of a major "Marshall Plan" for Africa. They do not realise that since 1960 Africa has benefited from the equivalent of several dozen Marshall Plans (the Marshall Plan brought Europe $13.3 billion between 1948 and 1952). Dambisa Moyo has calculated that Africa has benefited from more than $1 trillion since 1960. NGOs criticize donor governments for the lack of resources provided for ODA, but never for the lack of results.

The 0.70% ratio of the Gross National Income is still an official target. France decided in 2017 to move closer to it by increasing its ODA contribution by several billion euros to bring it up from 0.43% to 0.55% of GNI in 2022.

The goals set for ODA are the 17 UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) approved in 2015, i.e. general objectives such as no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, clean water and sanitation, the fight against climate change, peace, justice and effective institutions, etc. All countries might share these goals, but the question is whether ODA can make a significant contribution to achieving them. Past experience and the low financial contribution of ODA in relation to external financing received by developing countries raise serious doubts about this.

With its generous and general objectives, development aid policy seems surreal in aspect, ignoring our short and medium-term interests and failing to achieve the objectives that have been set. Contributing to gender equality or the fight against climate change in a foreign country does not impact us a priori. When so much taxpayers' money is being used, we should question whether more concrete priorities ought to be found to reconcile the interests of both recipient and donor countries.

All donor countries have specialised structures to manage official development assistance. These are based on a network of consultancy firms and NGOs which have acquired a certain expertise in traditional development activities carried out over the past decades, but which have every interest in allowing the present situation to continue. The governments receiving aid also form an effective lobby for its continuation. It cannot be hoped that the lack of concrete development results will lead the actors in these development aid networks to bring themselves into question.

Politically, it is impossible to question the principle of this policy, which is the subject of a broad international consensus. To make it evolve however, it is necessary and desirable to generate debate regarding the lack of tangible results after so many years and the possibility of setting win-win objectives for both donor and recipient. Without being exhaustive, we can propose possible avenues for development in areas such as the economy, migration regulation or military security.

Both donor and recipient countries have a vested interest in developing their economic exchanges. This is particularly true with Africa. Europe, and especially France, had a prominent place there and a good knowledge of the market, but have been largely ousted by the Chinese and Americans. We still have assets, especially because many African countries are beginning to fear Chinese expansionism. Like China, we could support our business investments in Africa and not hesitate to use official ODA funds for this purpose.

For many policy-makers, although not always officially expressed, the fear of migration from Africa is an important reason for justifying ODA. This is perfectly valid and one of the ODA's priorities should be to encourage all types of action to reduce migratory pressure.

Facilitating youth employment firstly means supporting countries that are firmly committed to a policy of promoting local agriculture. Indeed, agriculture accounts for more than half of all jobs in Africa, and it is the only sector capable of employing the millions of young people who enter the labour market every year. This presupposes a little pragmatism by Western countries, which must not pretend to support local agriculture, while dumping cut-price cereal surpluses there. African farmers, who grow a few hectares of low-yield maize, sorghum or millet, cannot be made to compete with the huge mechanised farms in Europe or the United States, where yields exceed ten tonnes per hectare. Europe and the United States must agree to African countries taking protectionist measures to support African agricultural jobs.

Much of Africa faces a security problem. Conflicts are ongoing in the Sahel, northern Nigeria and Cameroon (Boko Haram), Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Central African Republic, eastern Congo. There can be no development without security. African States'[4] budgets do not allow them to develop sufficient military capabilities to control jihadist movements, which know how to exploit the terrain and ethnic rivalries. European countries can effectively assist them with intelligence, training and military capacity-building. It is not in Europe's interest to allow jihadist movements to develop in Africa, so close to home. So far, generous minds have refused to include military expenditure when calculating ODA. This position needs to be reviewed, because restoring security is a priority for both Europe and Africa. ODA can contribute to strengthening our security.

In other areas, ODA intervention could be effective in the interest of both donor and recipient countries. This is the case in research, mainly in agriculture. Climate change and the need to find employment for the millions of young people from rural Africa entering the labour market will require the development of farming methods that are better adapted to the climate and to creating jobs. European research organisations could benefit from ODA funds to develop partnerships with the many African research institutes that are sorely lacking in resources. Research has the particularity of producing results that can be of interest to all partners.

ODA managers could also rely much more on the decentralized cooperation that has developed between local authorities in the North and South. As these are often small projects that sometimes mobilise only a few tens of thousands of euros, ODA financiers, used to managing millions of euros, do not appreciate them, as this type of small project is in their eyes too time-consuming. These are, however, concrete projects that are decided after level discussions between representatives of local authorities from the North and the South and which are conditioned by results as well as being monitored during periodic visits by partners. A simple and effective solution would be for ODA managers to trust European local authorities completely and to subsidize 50% of all their decentralized cooperation projects with local authorities in the South. In addition, a 50% subsidy would facilitate decision-making in municipal councils, where it is not always easy to gain acceptance of the interest of an action concerning a distant country, and would certainly lead to a strong increase in the action of local authorities in the North in favour of those in the South.

***

The European Union and the Member States finance more than half of official development assistance. This is a budget of more than €70 billion devoted yearly to sustainable development objectives for the recipient countries. Despite its importance for Europe, this sum cannot have a significant effect on the development of the countries of the South, as it represents less than 10% of the credits that these countries receive, either from remittances sent by migrants and diasporas or from direct investment by foreign countries (FDI). Experience shows that development cannot be brought about from the outside. Countries such as China, Vietnam or Singapore have shown that development is first and foremost the result of the firm will of a government relying on its own forces.

Under these conditions, current ODA policy objectives should be reviewed, establishing more concrete short and medium-term objectives that serve the interests of both donor and recipient countries. There are many possibilities, whether in the economic field, or in that of security or migration control or in the agricultural research sector. It is time to discuss them.

[1] L'Aide contre le développement ? L'exemple du Sahel, Editions Economica, Paris, 1988

[2] The Elusive Quest for Growth, Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics, MIT Press, 2001, 360 p.

[3] L'aide fatale : Les ravages d'une aide inutile et de nouvelles solutions pour l'Afrique, Editions JC Lattès, Paris, 2009, 250 p.

[4] Burkina Faso, for example has a budget equivalent to that of a French "département".

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :