Climate and energy

Emmanuel Tuchscherer

-

Available versions :

EN

Emmanuel Tuchscherer

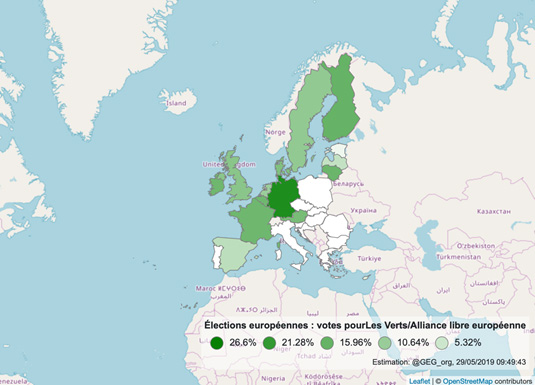

The rise of the green parties in the European elections is one of the striking factors this time round. Boosted by the ground taken in countries like Germany, France and the UK, the European Greens won 69 seats, 40% more than in the previous legislature[1]. To the backdrop of increasing public awareness of the challenges raised by climate change and the degradation of the environment[2], the rise in ecological stakes is also reflected in the "greening" of the programmes of other major political families at the centre of the European political arena. Social Democrats (S&D) and Liberals (ALDE) both support the goal to make Europe a carbon neutral economy[3] by 2050.

Votes won by the Greens/European Free Alliance in the European elections on 23rd-26th May 2019.

1. The carbon neutral goal

Irrespective of the coalitions that will be formed over the next few weeks in the European Parliament, all of the ingredients are there to make ecology and the acceleration of energy transition the main priority of the five years to come. The European Parliament, which is a co-legislator, will however have to negotiate with the Council of the European Union, which combines the interests of all Member States. Yet, the Council is full of political, economic and cultural divisions as far as ecological transition is concerned, and especially regarding the contentious subject of carbon neutrality. As a reminder: if the carbon neutrality goal is adopted, the Member States pledge not to emit more greenhouse gases than they are able to counter by way of carbon sinks i.e. forests, prairies and more in the long term, measures to capture and store CO2 by the middle of the century.

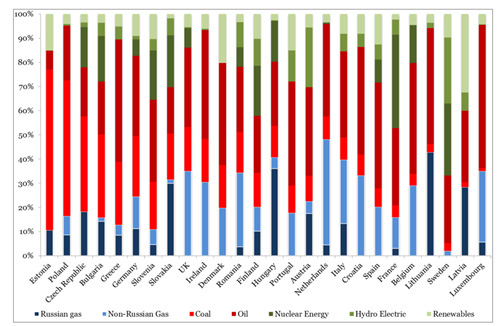

The European Commission has suggested that the Member States adopt this goal in its long-term strategic vision for the climate, deeming it inevitable, if the European Union is to honour the commitments it made in the Paris Climate Agreement. However, the 28 Member States do not agree on how to approach this. Ten countries or so, including France, Denmark, Spain, Finland, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden support this aim and are demanding a more ambitious climate policy. Others are avoiding the debate, for significant reasons: if we examine the issue of carbon neutrality more closely some difficult questions come to light in terms of the development of energy mixes (the place of coal), the protection of industrial competitiveness, and the social acceptability of ecological transition. Hence, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic do not support this goal. Germany approached the debate reticently at first, then in a more open manner. Chancellor Angela Merkel summarized Berlin's new frame of mind in the Petersberg Climate Dialogue at the beginning of May "It is not a question of knowing whether, but of how we can achieve this goal."

Member States' Energy Mixes (source : IEA)

The decision to turn carbon neutrality into a new European goal will have to be discussed again by the heads of State and government, in coming meetings of the European Council and to be decided by spring 2020 at the latest. For the Union, this debate will significantly affect all European policies that related the battle to counter climate change and to achieve energy transition. If carbon neutrality is adopted, European and national policies will have to be checked to see if they are adapted to this goal and if they are not, the additional work to be done to be achieve at all levels will have to be defined: financing, regulation, taxation, distribution of tasks between the different sectors of the European economy etc.

The target of carbon neutrality will not be binding. It will be used rather more as a benchmark to gauge the effort made by the Union and what remains to be done. It will define the level of ambition that the European Union has to set regarding climate and energy issues over the next legislature.

In this context we have to hope that the national executives will not back out of the real debate set by carbon neutrality. There is no question about the relevance of the goal: if Europe wants to respect the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement and contain the calamitous effects of climate deregulation, then it has no choice.

The UN's most recent report on the gap between requirements and perspectives in terms of reducing emissions points to the inadequacy of national contributions to contain rising temperatures to 2° and deems that these will rise to 3.2° by 2100, all commitments being equal.

The true debate lies with the adapted means to achieve the goal, by ensuring that they are politically, economically and socially sustainable. Carbon neutrality is a matter of civilisation, in that it involves a revolution in the way we produce and consume, in the way we behave and humankind's relationship with nature. But everything is making it politically very difficult, because there will be winners and losers, and it is challenging certain totems that have been set in place since the start of European integration.

We can identify four challenges to which the European Union will have to rise.

2. Containing the costs of ecological transition

We cannot close our eyes to the facts: because these costs will affect the energy prices, carbon neutrality will cause a negative supply shock, in the same way the oil crises did in the three post war decades (Glorious Thirty) in the wake of the rise in oil prices, but over a longer period of time. The figures at play in the decarbonisation of the European economy are significant and will affect consumers. The European Commission deems that to achieve the climate and energy goals by 2030, annual investments of 1,115 billion € will be necessary over the period 2020-2030. To achieve carbon neutrality, we shall require annual investments of around 2.8 GDP points by 2050. Zero-carbon transition means making sacrifices before we perceive any benefits.

Greening finance, introducing a grand investment plan, and, as suggested by French President Emmanuel Macron in his letter to the citizens of Europe in March last, a European Bank for the Climate to finance this transition, are a necessity if we are to climb the "investment cliff" associated with the zero-carbon transition. Likewise, it is imperative to green the European budget and to ensure that we can no longer finance spending that does not contribute to the greening of the economy. We also have to seek by all means possible to limit the cost, notably by the economies of scale enabled by a much more integrated approach on the part of European policies. We can quote several areas: the deployment of some major energy infrastructures, the coordination of carbon trajectories to avoid ecological dumping, financial transfers to the benefit of the regions that are most dependent on fossil energy to speed up inclusive transition. Containing the cost of ecological transition will therefore involve taking an additional step in terms of European integration. No headway has been made in this debate, whilst it should form the core of the future Commission's working programme.

3. Organising fair transition that protects the most vulnerable populations

Our European partners did not fail to notice that the revolt of the "Gilets Jaunes" in France was triggered by the contestation of an ecological tax measure, the carbon tax on fossil energy consumption. This movement forewarns of society's response to measures, which as they grow, will increase the negative redistributive impact of ecological transition on the poorest populations. They will be the first victims of the increase in energy bills and of the rise in the cost of consumer goods, as documented in a report[4]. Europe, which is striving to be "Zen" ("Zero émissions nettes" in French or net zero emissions), could very well turn into a Europe in crisis, if it triggers social revolt because the cost of transition for the poorest is not compensated by adapted public policy.

Ecological transition requires then that the European Union leave its comfort zone, which means the efficient organisation of the internal market, to develop social policies and a better articulated response to the challenges of energy poverty. A socially sustainable ecological policy would for example plan to direct a major share of funds to a "Green New Deal" and the energy renovation of buildings, particularly the very badly insulated ones in which the poorest live, and the change of heating solutions. Between 50 and 125 million Europeans are affected by energy precarity. Europe would offer a very real answer to these populations and at the same time, create, thousands of jobs in the building industry and energy services. Is Europe ready for the social reorientation of its priorities? We might question this when we see how little progress social Europe has made in the last twenty years, despite the declarations of intent and recently the rejection of the French President's proposal to introduce a European minimum salary on the part of the new CDU leader, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer.

The quest for a fair transition must flow into policies of solidarity between the Member States in support of industrial reconversion and jobs in the areas that are most dependent on carbon rich energies. Poland or Bulgaria's acceptance of this project will not be won if the European Union cannot offer locally integrated solutions to support the exit of coal and the reconversion of the most pollutant industries. The implementation of a "Green Marshall Plan" mobilising European funds and instruments to the benefit of these areas is more topical now than ever before[5].

4. Placing the European Union's economic weight and trade policy at the service of its ecological priorities

By opening up the debate over carbon neutrality Europe intends to confirm its political/diplomatic leadership, which lays emphasis on European climate exemplarity to produce a domino effect across the rest of the world. We must hope this because the additional efforts that the EU will place on itself to decarbonise its economy will in reality have extremely limited effect on total greenhouse gas emissions reductions. Europe is responsible for less than 10% of world emissions and will account for around 5% of these emissions in 2030. If it does not guarantee the reciprocity of its commitments, it may witness the relocation of its factories to countries that are not as demanding as far as the protection of the climate is concerned, and the emissions prevented in Europe will be transferred elsewhere in the world.

Indeed ecological transition represents a negative shock in terms of competitiveness for European industries, which is likely to penalise them in the world competition if nothing is done in compensation, either by obliging our trade partners to comply with our environmental standards, or by introducing tariff barriers on the Union's borders to re-establish the conditions of fair competition. To do this the main lever that the European Union has available is to condition access to its market of 500 million consumers with the respect of these standards. This means challenging the idea of free-trade held by a certain number of our European partners.

The poor response received so far to the French proposal of introducing an external carbon tax on the Union's borders, in order to place European and foreign industrial production on an equal footing, illustrates the technical and political resistance to this project. Significant efforts will be made to enable the ideological alignment of the Member States with unorthodox measures in the standards of free-trade, combining the protection of the climate with that of competitiveness. Hence, for several years we have spoken of integrating clauses in the free-trade agreements which subordinate access to the European market to the respect of social and environmental norms. The most liberal Member States are afraid of taking this path because they fear an acceleration of the protectionist vortex. And yet, the greater the gap between the standards that Europe sets on its internal market and the rest of the world, the hotter this issue will become as far as the climate and industrial competitiveness are concerned. It will have to define its own path so that it can get the best from world trade, protect its economic interests, whilst remaining true to its climate goals.

Finally, the fight to counter climate change should be made more central to the European Union's external relations. European energy investments on the African continent occupy an important position in the agenda of the new "Europe-Africa Alliance" announced in 2018 by the President of the Commission Jean-Claude Juncker. The European Union has the advantage of having the biggest leaders in terms of renewable energies, its geographic proximity and its historic and cultural links. Africa's needs are significant: 50% of Africa's Sub-Saharan populations have no access to electricity and the population is due to double by 2050. It is a time-bomb if the 2.5 billion Africans who will live in the middle of the 21st century inherit inefficient, highly carbonised energy systems. But the reality is that investments in energy are mainly led by Chinese public and private capital.

5. Transforming climate constraint into economic and industrial opportunities

Ecological transition does not just comprise drawbacks. The European Commission deems that the elimination of emissions will imply benefits estimated at 2 GDP points by 2050. Carbon neutrality could be a formidable political signal for the development of new green industrial branches in Europe that are good for growth and sustainable jobs. We might quote new generations of batteries amongst these "Greentechs", which are key to clean mobility, green gases and hydrogen, which are the missing link in the decarbonised energy system.

Europe does not lack the resources to introduce these new branches, but since there is no political consensus, it lacks the means to densify them, and to make the most of their potential in terms of growth, jobs and local development, and to protect them from unfair competition on the part of foreign operators. The dismantling of the nascent photovoltaic industry in the 2000's, devastated by Chinese dumping, serves as a case study for the future development of a European battery industry.

It is a real race against time that the European Union now faces if it is to establish these branches in Europe and bring them up to the expected level of competition. Massifying public support schemes to help them take off, organising calls for tender that allow a kind of European preference, relaxing the constraints of the competition policy, which is contrary to any type of industrial vision at present: all of these measures demand a deep aggiornamento of the Union's competition law and a consensus on the priorities to be given to a true European industrial policy. It will be difficult to form a compromise in the Member States and it will run up against the conservatism of the Brussels technostructure, as illustrated by the failed merger of Alstom and Siemens.

6. A roadmap for the next legislature

In view of these four challenges it is clear that a superficial orientation debate on carbon neutrality held by the executives on the overloaded agenda of the next European Council meetings might be singularly lacking in substance and lead to declarations of intention that will never be implemented. The importance of the issue demands an in-depth change in method to ensure that all of the forces at work in European civil society take part in the discussion over the transformations that Europe will soon undergo.

At a time when the main institutions of the European Union are being re-organised the answer to climate change calls for the organisation of European "Etats Généraux of Ecological Transition", to discuss all of the dimensions of the transition over to zero carbon. These Etats généraux might come after the appointment of the new President of the Commission and include, as it did in its time, the Grenelle de l'environnement in France, public leaders, those from the economic world, NGO's, professional federations and representatives of civil society. They would provide a unique opportunity to revive the European project - with the support of the citizens - around a shared vision of a Europe and ecological excellence. These Etats Généraux would provide a first response to the expectations expressed by Europeans during the most recent election.

These Etats généraux could be moderated by a Vice-President of the European Commission responsible for the coordination of all of the aspects of ecological transition, whose appointment would provide an excellent sign of the European Commission's (since it has the monopoly over legislative initiative) determination to move forward on this issue. To have impact, this Vice-President should have direct authority over the Commission's departments. The impression given by the Commission's departments when preparing the future legislative programme is rather that they want to play a low profile in the energy-climate chapter, after the present mandate, which has been prolific in terms of its texts on Energy Union, the reduction of CO2 emissions in the transport sector and the reform of the European carbon market.

***

Without the legitimacy of dialogue with civil society, the European Union might miss the necessary impetus to adopt extremely difficult, controversial measures, which will place it on the path of carbon neutrality. In the past politico-administrative obstacles have often led to unstable situations, involving extremely ambitious political goals followed by lukewarm, inadequate regulatory action. Hence, this applies to the energy-climate goals that the European Union gave itself in 2014, and then in 2018[6]. These goals set the extremely clear acceleration of effort in these sectors, whilst at the same time, European policies, which are not really integrated in the energy sector obliged the States to bear most of burden of the work to be done. Leaving the responsibility of success of these policies in the hands of penniless States, which lack administrative capacities or political will, is the best means to cause the failure of ecological transition and its loss of all credibility in the eyes of Europe's citizens.

Although carbon neutrality calls for a change in civilisation, the precondition for this is to take it to a public debate and to involve the citizens of Europe.

[1] The rise of the Greens will however be attenuated when Brexit becomes effective, with the number of seats dropping from 69 to 62 with the departure of the British ecologists.

[2] The issue of climate change is at the heart of European citizens' concerns. It is perceived by 16% of Europeans, according to the April 2019 Eurobarometer, as being the fifth biggest problem that the Union faces.

[3] The term "climate neutrality" is also used.

[4] The distributional effect of climate policies, Bruegel , November 2018.

[5] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/european-issues/0465-towards-energy-union-act-ii-a-new-european-energy-climate-leadership, Robert Schuman Foundation European Issue 465, March 2018

[6] These bring the effort to reduce greenhouse gases up to 40 %, the effort for energy efficiency up to 32.5 % and the development of renewables up to 32 % by 2030.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Climate and energy

Gilles Lepesant

—

14 January 2025

European social model

Fairouz Hondema-Mokrane

—

23 December 2024

Institutions

Elise Bernard

—

17 December 2024

Africa and the Middle East

Joël Dine

—

10 December 2024

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :