Institutions

Charles de Marcilly,

François Frigot

-

Available versions :

EN

Charles de Marcilly

François Frigot

A tumultuous presidential

In spite of the victory of the European People's Party (EPP) in the European elections, it supported Martin Schulz in July 2104 who stood for a second mandate as President of the Parliament. In all, with the support of the Liberals (ALDE), Martin Schulz won 409 votes following an agreement concluded by the "grand coalition" after the European elections. The agreement provided that an EPP candidate would succeed Martin Schulz mid-mandate. This tacit agreement of alternation between the EPP and S&D groups for the presidency has always been customary except in the case of the Irish Liberal Pat Cox, who was president from January 2002 to June 2004.

These agreements rely on a compromise between the main political groups, which is mirrored at inter-institutional level. This became notably clear on 13th December 2016 when the Presidents of the three institutions - Parliament, Council and Commission - signed the first joint declaration defining the goals and priorities of the European Union's legislative process in 2017. Yet, on the same day, the leader of the S&D group Gianni Pittella announced that the "grand coalition" was no longer valid. These two announcements highlight the difficulty the European Parliament has in being a political tool. A certain amount of frustration is emerging regarding the supervision of the coalition. If the latter were to disappear, agreements based on variable geometry would weaken Parliament in its ability to provide collective impetus to potential hesitations on the part of the Member States.

As a result the election of the new President of Parliament was a lively[1] affair: the EPP candidate - Antonio Tajani - and S&D Gianni Pittella were running neck and neck in the fourth round of the relative majority of the votes cast[2]. This was the first time this had happened since 1982. The ALDE candidate Guy Verhofstadt withdrew before the first round in exchange for an agreement with the EPP candidate, five other candidates were still in the running. The latter each received the support of their respective group until the fourth round, which only retains the two candidates that come out ahead. In the last round Antonio Tajani won 351 votes with the support of the ECR group, against 282 for Gianni Pittella and 80 abstentions. Now the three main institutions of the European Union are presided over by an EPP representative.

The eight political groups[3] in the European Parliament also re-elected their leaders. Manfred Weber (EPP; Germany), Gianni Pittella (S&D; Italy), Guy Verhofstadt (ALDE; Belgium), Syed Kamall (ECR; UK), Nigel Farage (EFD; UK), Gabriele Zimmer (GUE-NGL; Germany) were confirmed as the leaders of their groups[4]. The traditional co-presidency was supported in the Greens/EFA group with Philippe Lamberts (Belgium) and now Ska Keller (Germany), as well as in the ENF group created in June 2015, which will again be co-chaired by Marcel de Graaff (Netherlands) and Marine Le Pen (France).

From safe arithmetic to variable geometry

The upkeep of unity in the "grand coalition" regarding the proposals made by the European Commission relies on generalist parliamentary work, without any major issues of conflict, which are of a mainly non-legislative nature. Position taking over a wide range of subjects complements what is now traditional regulatory action. Mid-mandate polarisation between the two main groups could modify the balance. Since the start of the 8th legislature the "coalition", formed by the EPP and S&D groups has remained hegemonic within the Parliament in terms of the approval of most of the most important acts, thereby supporting the Commission's working programme. With 406 MEPs (217+189) out of 751 they hold a majority that is completed by the other political groups in a case by case situation, notably by the ALDE and Greens/EFA groups regarding some major votes. More rarely the grand coalition has been divided, but this has not prevented the emergence of major but relatively weak alternative majorities: the report on the implementation of the energy efficiency directive[5], for example only received 51% of the vote[6] on the part of the GUE/NGL, Greens/EFA, S&D, ALDE and EFD groups, without the support of the EPP. More often however, we see a majority formed by the votes of all or nearly all of the political groups. In the case of the draft resolution on granting China the status of market economy[7], the text was approved by 84% of the vote and only the ENF opposed it, whilst the latter proposed a motion which 641 votes rejected.

Moreover, the constant split that emerges from the analysis of the votes in 2016 lies between the political groups which support the European Union and those which are against it. The EFD and ENF groups are sometimes the only ones to oppose the approval of some of the texts. This was the case with the draft legislative resolution on the conclusion of the Paris Agreement on behalf of the European Union approved by 90% of the vote, by all groups except for the EFD and many ENF MEPs, who rebelled against the party's position (abstention). The limited level of coherence between the Eurosceptic groups prevents any credible alternative projects, which might win the support of the other groups. However, for some Eurosceptic groups, rejecting the EU is only strategically useful as long as the danger of really leaving is low. In this light the aborted attempt by the Italian 5 Stars Movement (M5S) to join the ALDE shows the wish to distance themselves from the toxic nature of the truly Europhobic wings of the EFD.

The Front National, the leader of the ENF group, has still not found any allies for a political alternative. Although its action is part of the parliamentary work (rather more attendance in committees and proposing resolutions, motions) its suggestions have not found any echo in Strasbourg for the time being.

In this context the challenge made to the "grand coalition" makes the future more uncertain within the institution. From safe arithmetic (217+189), agreements will be made according to variable geometry with alternative majorities. The next 30 months will be marked by the return of politics and agreements on a case by case basis on major issues, which will mechanically lead to more concessions on the one side and the other in order to guarantee support to the legislative proposals. Each parliamentary committee might run according to its own rationale. The biggest delegations within the groups will take advantage of this dispersion. This rearrangement also offers leverage to average sized groups (ALDE with 68 members and/or ECR with 74 MEPs). Depending on the issue in hand and specific alliances, they might become the "deal makers". In addition to this it is of mutual interest for the EPP and S&D groups, without making it official, to make the agreement passed regarding major issues in this legislature permanent. However, on many themes political continuity with the first part of the legislature should prevail. It will be the responsibility of the group leaders to ensure that agendas converge to maintain a certain amount of unity, notably regarding the other institutions.

Relative stability within the Committee Chairmanships

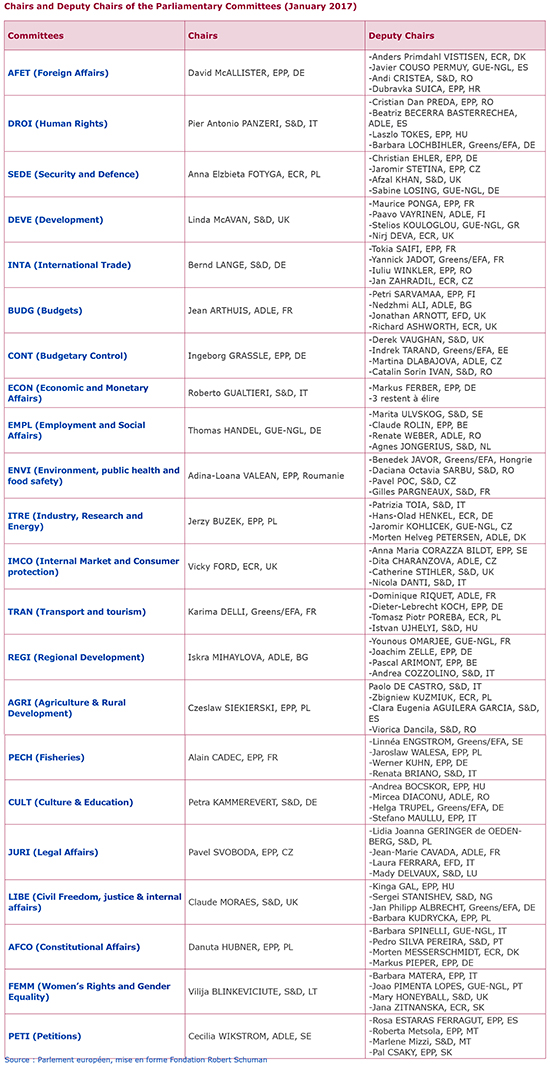

The 22 permanent parliamentary committees are linked to the various areas of European policy. Each parliamentary committee comprises between 25 and 70 members including a Chair, Deputy-Chairs, and a Secretariat, elected for a two and a half year mandate. The 22 committees share out the issues under discussion and subsequently voted on by the institution. Distribution amongst the MEPs within the committees is the focus of agreements between the political groups according to their relative weight, national delegations, balances between countries and individual wishes/leanings.

If current events in Europe raise one or two specific issues Parliament is allowed to set in place temporary committees. Under the 8th legislature two temporary committees have been established: one measuring emissions in the automotive sector (EMIS) and another regarding capital laundering, tax fraud and evasion (PANA). In the event of the infringement of community law or an allegation of poor administration in the implementation of Union law committees of inquiry are created by the Parliament.

The chairmanship of these committees is assumed by different political groups. This political representation remained stable in the period covering 2014-2016 and this will continue in 2017-2019, since all of the major political groups retain the same number of chairs within the committees. With their weight in the Parliament the EPP and the S&D retain the majority, with respectively 8 and 7 committee chairs. The ALDE has three committee chairs, ECR 2, GUE/NGL and the Greens/EFA 1 each.

Of the 22 committees 16 Chairs were re-elected to their post. Six portfolio changed hands. As agreed at the start of the legislature, Michael Cramer (Greens/EFA, DE) from the Transport and Tourism Committee (TRAN) has been replaced by Karima Delli (Greens/EFA, FR). The Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee (AFET) remains in German hands and the EPP, but the Chair is new in the shape of David McAllister, who has taken over from Elmar Brok. Italy lost the Chair of the Culture and Education Committee (CULT) to the benefit of Petra Kammerevert (S&D, DE). Italy also lost the Chair of the Environment Committee, Public Health and Food (ENVI) that was attributed to Adina-Ioana Valean (EPP, RO). Spain lost the Chair of the committee on Human Rights (DROI) to the benefit of Italy, which appointed Pier Antonio Panzeri (S&D) and the committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM) to the benefit of Lithuania, which appointed Vilija Blinkeviciute (S&D). No Spanish will be chairing a parliamentary committee in 2017. The same goes for the Austrians, Belgians, Cypriots; Croats, Danes, Estonians, Finnish, Greeks, Hungarians, Irish, Luxembourgers, Maltese, Dutch, Portuguese, Slovakians and Slovenians. Moreover Austria, Ireland, Lithuania, Slovenia, Lativa and Cyprus no longer have any MEPs amongst the Committees.

From 2014 to 2019 Germany has and will remain dominant within the committees with five chairs. Poland has four. Italy lost the chair of some committees in 2017, but this is compensated by the Presidency of the European Parliament. France has increased from two to three committee Chairs (Fisheries, Budgets, Transport). The most surprising figure is that of the 3 chairs retained by the British MEPs in spite of the referendum vote on 23rd June 2016.

The quality of British MEPs is recognised and they are full members of the Parliament as long as their country has not officially left the European Union. However, it might have been logical to see its citizens withdraw, notably following the government's choice to privilege a "hard Brexit"[8]. However, they have retained many posts. Hence the UK has three committee chairs: (Development (DEVE, chaired by Linda McAvan); the Internal Market (IMCO, chaired by Vicky Ford, who has been in post for more than 12 years) and Civil Liberties, Justice and Internal Affairs (LIBE, chaired by Claude Morales), whilst the latter will have to vote on data protection, the legislative package on asylum and migration and the EU's relations with the USA. Between 2014 and 2017, the UK went from four to seven Deputy Committee chairs, retaining two group leaderships (Syed Kamal, ECR and Nigel Farage EFD) and a Vice-Presidency, as well as winning one other.

Hence, what is the political logic for the institution in leaving some responsibility in the drafting of legislative power to a country that will no longer live with the consequences of the exercising of this same power? It cannot be ruled out that there will be no conflict during negotiations over the budget, the question of the future distribution of the British MEP seats[9], and the Brexit procedure.

Source : Parlement européen, mise en forme Fondation Robert Schuman

Source : Parlement européen, mise en forme Fondation Robert Schuman

Remark: 2 temporary committees, EMIS andPANA

-EMIS (Measurement of emissions in the automotive sector) ; Chaired by Kathleen VAN BREMPT, (S&D, BE) ; Deputy-Chaired by Ivo BELET (EPP, BE), Mark DEMESMAEKER (ECR, BE), Katerina KONECNA (GUE-NGL, CZ) and Karima DELLI (Greens/EFA, FR)

-PANA (Laundering of capital, tax evasion and fraud); Chaired by Werner LANGEN (EPP, DE); Deputy-Chaired by Pirkko RUOHONEN-LERNER (ECR, FI), Fabio DE MASI (GUE-NGL, DE) and Eva Joly (Greens/EFA, FR)

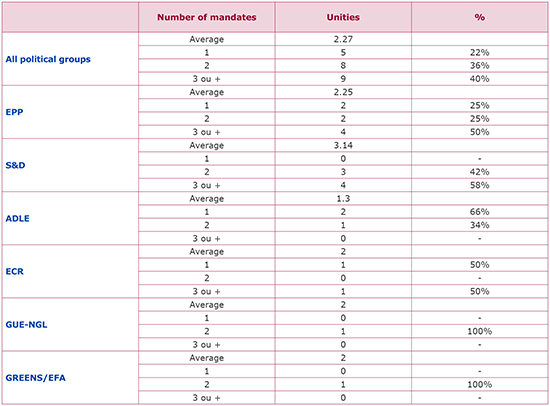

Remaining to chair better?

The analysis of all of the MEPs experience explains in part their promotion or their upkeep in key posts in the European Parliament. The three British committee chairs have completed four mandates, i.e. more than the 1.6 mandates of the three French chairs and the 2.8 mandates of the 5 German chairs. Hence, in spite of the lack of political coherence, the weight of the British delegation in the European Parliament and the long hard work of some of its citizens explains why they have remained as head of some of the most important committees. As for the Germans, who retain their hold over their executive positions in the European Parliament, longevity is also an important factor. It bears witness to the long term work of its MEPs who have undertaken nearly 3 mandates on average before being elected as committee Chair. This is further confirmed by the reduction of the average on David MacAllister's appointment as head of the Foreign Affairs Committee during his first mandate. Elected MEP in 2014 and appointed Vice-President of the EPP in 2015, his rapid rise bears witness to a national strategy on the part of the Germans to retain an important committee, Foreign Affairs, since Mr MacAllister has taken over from Elmar Brok, who was Chair between 1999 and 2007 and then from 2012. In a complicated diplomatic context, since the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit referendum vote last June, the upkeep of two German MEPs affiliated to the German government coalition, David McAllister in Foreign Affairs and Bernd Lange (S&D) in International Trade shows a national determination to retain its influence in these areas.

Average calculated on the exact detail of the number of MEP mandates undertaken by each Chair

Average calculated on the exact detail of the number of MEP mandates undertaken by each Chair

Data source European Parliament, calculated and processed by the Robert Schuman Foundation, January 2017

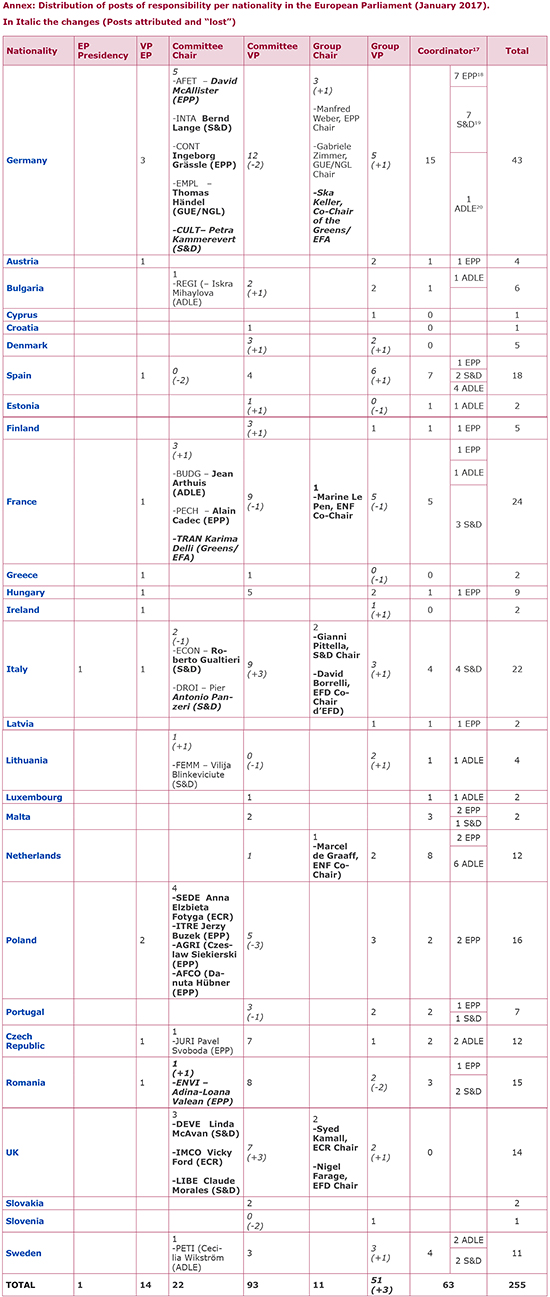

Key Posts in the European Parliament: Germany in the lead

The distribution of posts of responsibility in the European Parliament is far from being fair between the Member States. Indeed nearly 73.5% of the posts of responsibility[10] in Parliament are occupied by 10 different nationalities only. The remaining 6.5% are shared between 18 countries. The distribution of posts of responsibility between the MEPs of the Member States in the European Parliament remains largely dominated by the Germans. Germany is the country which has accumulated the most executive posts in Parliament with nearly 17% of the posts after the most recent renewal. France, Italy and Spain lie far behind Germany with 9.5%, 8.5% and 7% of the posts respectively.

This increase can be seen in high profile political posts, but also in more discreet, yet vital areas of the "compromise factory", which the Parliament indeed is. Not very well known, the coordinators are amongst some of the institution's most influential players. These MEPs are heads of their political group within the committees: distribution of reports, amendment negotiations definition of the group's position during voting; they are the lynchpin in the political compromises. Although not all have yet been appointed by their political groups we some trends are emerging if we look at the known coordinators within the two main groups - the EPP and the S&D- and the ALDE party, the 4th political force in the Parliament.

Germany has 7 EPP [11] and the S&D 7 coordinators in the 22 committees. Hence, in these political groups 30% of the coordinators are German. The Italians and the French have 4 and 3 S&D coordinators respectively. Poland has 2 EPP coordinators. The ALDE group is marked by the size of the Dutch delegation, with 6 coordinators and Spain with 4.

Moreover the distribution of these posts between the Member States again shows that Germany is in the majority. Apart from the importance of their delegation within the EPP and the S&D, their coordinators are distributed in the most important committees, which are already chaired by Germans: for example, Knut Fleckenstein (S&D) and Robert Neuser (S&D) in the Foreign Affairs Committee.

Although the lack of data for the ECR and EFD groups is regrettable it is not detrimental since these groups are dominated by a small number of delegations (France, Poland, Italy) that could distort the analysis of the Member States' weight within the numbers of committee coordinators.

A swing to the East in the European Parliament?

The election for the leader of the European Parliament might have seemed as a misleading "Italy-Belgium" match with 3 and 2 of their citizens taking part respectively out of the seven candidates[12]. Although Italy runs neck and neck in terms of the distribution of posts of responsibility with the British, Belgium does not have enough powerful relays to achieve, for example, a committee chair, but relies on two group leaderships (21 Belgian MEPs). The number of MEPs, their distribution and therefore their respective weight within the main political groups and also the collective approach independent of their partisan leanings dictates this balance.

Apart from the maintenance of the German (quantitative) and British (qualitative) influence, the renewal of key posts in the European Parliament mid-mandate has led to a certain re-organisation in the traditional balance between the Member States that are represented, reflecting a swing to the East. In the last renewal Portugal lost one committee Deputy-Chair, without any compensation being made. Spain, the Union's fifth demographic power lost two Committee Chairs during the renewal.

At the same time the increase in the influence of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe is visible on two levels[13]. For example, if we look at the distribution of the posts of committee Deputy-Chair, we note that in terms of numbers of Member States like the Czech Republic with 6 Deputy-Chairs, it easily draws ahead of a similar sized country like Portugal (3). Moreover, since January 2017 the Czech Republic has a Parliament Vice-President in the shape of Pavel Telicka (ALDE), just like Spain. The presence of these Czech MEPs is all the more noticeable due to their political division. Amongst the Deputy-Chairs, we note one EPP MEP, one ECR, one GUE-NGL, one S&D and two ALDE. More significantly one Member State with 20 million inhabitants like Romania has 2 Deputy-Chairs more than France (8 against 6). Although in 2017 Romania lost two group Deputy-Chairs, its 2 Vice-Presidents in Parliament remained.

Likewise Poland has two Vice-Presidents in Parliament and 4 committee Chairs, i.e. more than France, Spain and the UK. Even if this rise in the ranking has been reflected quantitatively in the loss of 2 Commission Vice-Presidents, it bears witness to a significant rise in influence on the part of Poland and the countries that were produced by the dynamic of enlargement to key posts in an increasingly eastern Parliament. To do this the Polish MEPs use the concentration of their strength as the second delegation of the EPP (23 MEPs) and the ECR (19).

Parity increasing

Article 204.1 of the European Parliament's regulation (Title VIII, Chapter I) stipulated that the office of each committee cannot be exclusively male, nor exclusively female and that the Deputy-Chairs cannot be just from one Member State alone. The determination to respect parity within the European institutions shows fair and respectful governance of the latter. Regarding the share of men and women amongst the institution's Vice-Presidents between the two mandates we note that there has been no development (9 men and 5 women), whilst three changes have maintained this distribution.

However the chairs the parliamentary committees were dominated by men between 2014 and 2016, but now there is gender balance with 11 respective chairs. Amongst the questeurs, we note a balance of 3 men and 2 women but the first is Elisabeth Morin-Chartier (EPP, FR).

This can also be seen within the committees of inquiry. For example in the EMIS committee, Kathleen Van Brempt was appointed Chair, and two of the four Deputy Chairs are women. Regarding the PANA committee, although the Chair is a man, three of the four Deputies are women. In spite of everything the parliamentary committee Deputy Chairs are far from being totally equal with 53 male Deputy Chairs against 33 women Deputies. This has delayed some appointments. On 25 January 2017, the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee (ECON) announced the appointment of Markus Ferber as Deputy Chair but it did not communicate the names of the three other Deputy-Chairs because the candidates were not evenly mixed. The same applied to the committee responsible for budgetary issues.

European Parliament has slightly more than 37% female MEPs, whilst in the Member States they only represent 26.68% of the ministers and 29.07% of national parliamentarians.

What should we expect over the next two years?

The coalition agreement concluded after the elections in 2014 was criticised for its total support to the proposals made by the European executive as it assumed a reduction in political divisions to the benefit of greater visibility. This strategy now seems to have reached its limits.

In a context of fewer legislative texts, the internal competition to be a rapporteur or to win posts of responsibility and by extension a higher profile is growing. The distribution of responsibilities mid-mandate shows that the citizens of the biggest demographic States have kept the main posts. However we note a refocusing from the south to the east of the European Union in certain positions. The upkeep of the British is an incongruity in view of the Brexit and of the collective will of the MEPs to have their say in future debate.

As illustrated by the positions adopted over the British referendum there is a certain danger of drifting towards a "YouTube Parliament" for which the image and taking the floor in plenary would take precedence in terms of communication over co-legislation and regulatory activity. Although the interest of media coverage and the broadcast of parliamentary exchange to the public is a vital step forward in terms of bringing the institutions closer to their citizens not all parliamentary activities weigh the same and a rationalisation of the "tools" used has been necessary. Thought about this has led MEPs improving their work efficiency. Supported by 548 MEPs on 13th December the report by Richard Corbett helps define the number of written questions, motions, resolutions and requests for roll-call votes. Likewise, written questions which reached an excessive level of 60,000 per year without showing their effectiveness,, will now be limited to 20 per MEP over a three month period[14]. This report also provides for the possibility of the political groups putting forward topical debates.

Likewise there is a development towards more weight being given to co-decision, such as the use of the trilogue on first reading, offering a rapid possibility of a negotiation mandate to strengthen Parliament's influence during the decision making process. Concern is rising about the transparency of this process and the European Ombudsman asked for the publication of the documents produced during these meetings[15]. The answers provided by the institutions were firm regarding the necessary discretion of the trilogue process, the transparency of which is not due to improve in the short term[16].

Finally the real challenge in the second part of the legislature will be for the MEPs to make their voice heard in a turbulent international context. Uncertainty outside of the Union, together with internal divisions over several political issues require coherent, coordinated response on the part of the institutions. The (theoretical?) end of the grand coalition is weakening more than it is supporting the institution, which can however rely on its delegations and experienced committees.

Source : European Parliament and Political Groups : processed by François Frigot

Source : European Parliament and Political Groups : processed by François Frigot [1] For the exact sequence of events read Leonor Hubot, " Deux Italiens pour un perchoir... Et un seul vainqueur ", www.Bruxelles2.eu , 18th January 2017 (in French)

[2] Except if stated otherwise all of the data quoted come from the European Parliament

[3] At present 18 MEPs belong to no specific group and are identified as "non inscrits"

[4] Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), Unified Left-Nordic Green Alliance (GUE-NGL), Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA)

[5] European Parliament, " Resolution on the report on the implementation of the directive on energy efficiency (2012/27/UE) (2015/2232(INI)) ", 23rd June 2016

[6] The voting percentages come from VoteWatch

[7] European Parliament, " Resolution on China's status as a market economy (2016/2667(RSP))", 12th May 2016

[8] Theresa May's speech, 17th January 2017

[9] Robert Kalcik and Guntram B.Wolff, "Is Brexit an opportunity to reform the European Parliament?", Bruegel, 27th January 2017

[10] See the table in annex. Presidents and Vice-Presidents of the institution, Chairs and Deputy Chairs of the parliamentary committees and of the political groups are counted as well as the post of questeur and coordinator. Naturally all of these posts are not equal in terms of their political weight. It is just a quantitative indicateur.

[11] Not counting the Deputy-Coordinators not included in this study

[12] Belgians Guy Verhofstadt (ALDE), Helga Stevens (ECR), Briton Jean Lambert (Greens/EFA), Italian Eleonora Forenza (GUE/NLG), Romanian Laurentiu Rebega (ENF).

[13] We already identified this phenomenon in 2014 " French influence by its presence in the European institutions " European Issue No348, Robert Schuman Foundation, 16th March 2015

[14] We already noted this inflation and that this revealed " Review and Lessons of the 7th Legislature of the European Parliament, 2009-2014 ", European Issue No308, Schuman Foundation, 7th April 2014

[15]"Ombudsman calls for more trilogue transparency", 14th July 2016

[16] Harry Cooper and Quentin Aries, "POLITICO Brussels Influence: Behind closed doors ", 27th January 2017

[17] It was not possible to collate ECR, Verts/ALE, GUE/NGL and ENF group data , since these parties have not yet appointed their coordinators.

[18] Collation of data on the EPP: http://www.eppgroup.eu/fr/structure

[19] Collation of data on the S&D : http://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/

[20] Collation of data on the: http://www.alde.eu/fr/

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Enlargement and Borders

Snizhana Diachenko

—

12 November 2024

Internal market and competition

Jean-Paul Betbeze

—

5 November 2024

Freedom, security and justice

Jack Stewart

—

29 October 2024

Democracy and citizenship

Elise Bernard

—

22 October 2024

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :