Freedom, security and justice

Philippe Delivet

-

Available versions :

EN

Philippe Delivet

The free movement of people is a fundamental acquis of European integration. Introduced as part of the internal market it assumed a wider dimension with the Schengen Agreements. And yet real difficulties have affected the dynamic of free movement. It has suffered due to the slowing of the internal market and the serious impact of the crisis. It is also suffering due to rising concern about external migratory pressure in a context of enlargement. In particular this is encouraging fears of social dumping. Pinpointing these difficulties is vital if we are to provide pragmatic answers without endangering the founding principle. Free movement reveals a major challenge to the economic and social convergence which the European Union has to overcome.

I/ The free movement of people: a founding principle of European integration

Asserted in the Treaty of Rome, the principle of free movement has developed as part of the internal market. It took on a wider dimension with the Schengen Agreements. This principle is also indissociably linked to European citizenship of which it is a major achievement.

1/ The introduction of free-movement as part of the internal market

The free movement of people cannot be separated from the original project to create a large, unified internal market. The Rome Treaty set the goal therefore of establishing a Common Market of free movement of merchandise, people, services and capital designed "a harmonious development of economic activities, a continuous and balanced expansion, an increase in stability, an accelerated raising of the standard of living and closer relations between the States belonging to it."

European citizens consider free movement to be the major achievement of European integration. 57% of them quote this as being the most positive result achieved by the European Union, even ahead of peace (55%).[1]

Free movement covers the right to enter and circulate within the territory of another Member State, as well as the right to stay there, to work and live under certain conditions, after occupying a position of work. Confirmed in the Treaty on European Union (art 3), the freedom of movement is also guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights (art. 45) and by the Jurisprudence of the Court of Justice.[2]

The measures applicable were grouped together in the directive (2004/38) of 29th April 2004.[3] Every citizen in the Union has the right to travel freely to another Member State and remain there for a short period of at least three months without having to show any document other than his valid ID card or passport. No entry visa can be demanded; the European citizen is not obliged to have a job or to have sufficient resources. For stays over three months the directive defines the categories of people who enjoy the right to free establishment, particularly paid or non-paid workers and the members of their family, on reserve that certain conditions are fulfilled. The Union's citizens who have legally stayed for an uninterrupted period of five years in a Member State acquire the right to permanent residence. Measures were taken to ensure the transferability of social security rights (regulation of 14th June 1971 (1408/71) and of 30th April 2004 (883/2004)).[4] The field of benefits is vast (sickness, maternity, old age, accidents at work, unemployment and family allowance) but does not cover social and medical assistance that can be reserved to nationals only.

2/ The Schengen Agreements

With the Single Act in 1986 the Member States accepted, regarding decisions affecting the internal market, the principle of the qualified majority vote rather than unanimity, which enabled an acceleration of the process. The "borderless" internal market officially began on January 1st 1993. But it seemed hard to imagine lifting obstacles to the free movement of merchandise and leave the restrictions to the free movement of people unchanged. As part of an intergovernmental cooperation agreement five States (Belgium, France Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Germany) signed the Schengen Agreements (1985) and their implementation convention (1990). Within the Schengen Area the signatory States abolished their internal borders in exchange for a single external border on which entry controls were made according to identical procedures.[5] More than 400 million Europeans could now travel without a passport. The right to a short stay also benefited the citizens of third countries who found themselves within the Schengen Area. The Schengen cooperation became part of the legal framework with the Amsterdam Treaty in 1997 (art. 67 TFUE).

3/ Free movement and the European citizen

Free movement is closely linked to European citizenship which was introduced with the Maastricht Treaty (1992) from which came the Treaty on European Union (TEU). Article 9 TEU specifies that anyone who holds the nationality of a Member State is a Union citizen. The Court of Justice stresses that the European citizenship aims to be "the fundamental status of the citizens of the Member States (decision 20th September 2001, Grzelcyzk). Beyond the principle of equality TFEU (art. 20 to 25) sets out the list of rights that result from European citizenship. Some of these rights are specific to European citizens and distinguish them from third country citizens. The Council, voting unanimously, can, after consultation with the European Parliament adopt measures regarding social security and social protection to facilitate the exercise of free movement. (art. 21 §3 TFEU).

The right to free movement granted to the citizens of Europe also results from the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which is now legally binding. Its Preamble says that the Union "places the individual at the heart of its activities, by establishing the citizenship of the Union and by creating an area of freedom, security and justice."

Some 14 million European citizens have chosen to work or live in another Member State and benefit from social protection and civic rights. The Erasmus programme has already involved 3.5 million students who have undertaken higher education in another State other than their own. Around 1.1 million workers benefit from the right to free movement.

II/ Real problems that have impeded the dynamic of free movement

Several difficulties have impeded the dynamic of free movement. They have gained in greater acuity in a context that has been marked by the consequences of the economic and financial crisis and sovereign debts.

1/ The weakening of the rationale of the single market

Free movement developed in close association with the construction of the internal market. However the dynamic of the latter has progressively weakened. In his report of May 2010[6], Mario Monti notably stressed the erosion of political and social support to the integration of Europe's markets. A Eurobarometer survey[7] showed that 62% of Europeans felt that the single market was only benefiting big companies; 51% that it was worsening working conditions and 53% that it presented few advantages for the vulnerable. According to the Monti report, the legal framework for the free movement of people was still incomplete.

2/ The effects of the economic and financial crisis

The crisis had a major impact on the single market. Between 2008 and 2009 the Union's GDP contracted by 700 billion €. Nearly 5 million people lost their job. Youth unemployment is a major concern. It represents more than double the overall unemployment rate (18.8 % against 8.3% in November 2016) with great disparity between the countries: an extremely sharp difference lies between the Member State with the lowest rate (Germany 6.7 %), and the Member States with the highest rates (Greece, 46.1%; Spain, 44.4 % and Italy, 39.4%). In November 2016, 4.2 million young people under 25 were unemployed.[8]

3/ Concern about the migratory flows and the terrorist threat

In the context of the "Arab Spring" in April 2011 the rules applicable to the Schengen Area (the Schengen border codes) were the focus of a Franco-Italian request for adjustment. The Commission then put forward a proposal that enabled the re-introduction of border control as a last resort, for a limited period of time (6 months renewable up to 2 years), in the event of serious, continued problems on one of the external borders.

The migratory crisis and the repeated dramas that have occurred in the Mediterranean have highlighted the pressure on the common borders. 180,746 people reached the Italian coasts in 2016.[9] The figure totalled 154,000 in 2015 and 170,100 in 2014. Nigerians (36,000), Eritreans (20,000) and Guineans (12,000) comprised the biggest contingents of migrants in 2016. In 2015, Greece received 857,000 migrants, i.e. 80% of all migrants entering the EU via the sea. For Greece this represented a 20 fold increase in the number of arrivals in comparison with 2014. These events pointed to the limits of European migration policies and the weakness of solidarity between the Member States.

The other issue of concern is linked with the extension of free circulation and the enlargement of the EU. Since January 1st 2014 the citizens of the new Member States have the right to work in any Member State they wish.

The result of this has been extreme concern expressed notably by D. Cameron in an article published in the Financial Times[10], then in a letter addressed on 10th November 2015 to the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk. The British Prime Minister used the steps undertaken by the Austrian, German and Dutch Home Affairs Ministers with the European Commission to assert that the UK was not the only country to consider that free movement should be better managed.[11]

The situation of the Roma has also contributed to controversy. It is believed that 10 to 12 million Roma live in Europe, 8 million of whom in the European Union. The implementation procedures of the 2004 directive were the focus of debate between France and the European Commission in 2010 regarding the conditions for the dismantling of the Roma camps and the measures used to remove them from the country.

Even though it did not take place in a country that is not an EU member the Swiss vote of 9th February 2014 that decided to challenge free movement between Switzerland and the Member States could not go without effect regarding the conditions of free movement within the EU itself. The new constitutional article stipulates that the new Swiss migratory policy will be subject to contingents and caps, whilst being directed towards a gauge of "overall Swiss economic interests" and in the respect of national preference.[12]

Finally the attacks that struck Europe in 2015 and 2016 have sharply highlighted the facility with which the terrorists have entered and travelled around within the European area.[13]

4/ The fear of social dumping

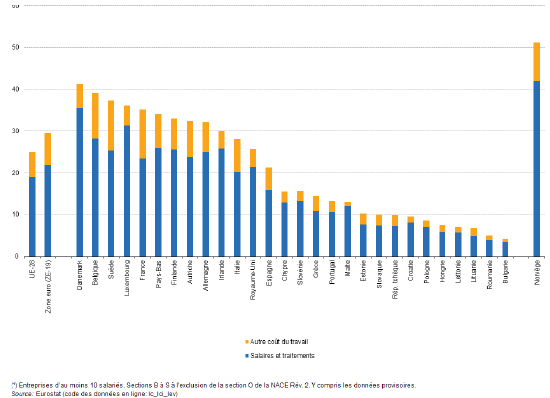

The fear of social dumping in Europe also focused attention on the impact had by free movement. It was expressed via the observation of differences in labour costs. The average hourly cost of labour was estimated at 25.03 € in 2015 and 29.5 € in the euro zone. But this average does not cover significant differences between the Member States, since the average hourly cost varies from 4.08 (Bulgaria) to 41.31 € (Denmark). The share of non-wage costs, like social contributions paid by employers, totals 24.4% in the EU and 26% in the euro zone. Again disparities between States are high: 33.2% in France, 32.1% in Sweden against 13.7% in Ireland and 13.9% in Denmark.

Hourly cost of labour 2015 (in €)

Source: Eurostat

It then formed around the debate regarding posted workers. This procedure is founded in the treaty which acknowledges the right to the free provision of cross border services (art. 56 TFUE). According to the European Commission the number of posted workers in the EU lay at 1.9 million in 2014 i.e. 0.7% of all jobs in the Union. Germany, France and Belgium host around 50% of all posted workers. Reciprocally Poland, Germany and France are the three Member States which post the most workers. The average duration of a posting per worker lies at around 4 months.

The building sector is the biggest user of posted workers (43.7%), particularly in SMEs. But the use of posting also exists in the manufacturing industry (21.8%), services linked to education, healthcare and social action (13.5%) and services to businesses (10.3%).

A 1996 directive guaranteed posted workers imperative rules of set protection in the Member State in whose territory the work was being undertaken. Employees and working conditions are those of the host country. However social contributions are those of the country of origin. An employer can therefore have labour at a lower cost by recruiting workers from countries where social contributions are the weakest.[14]

Source - Centre for European and International Social Security Liaison

In a tense labour market situation, fingers were pointed at the abuse of rules provided for in the directive. A lack of legal certainty prevents an accurate assessment of the reality of posting. Moreover the States' (which do not cooperate enough) weak capacity to monitor the respect of the rules has been highlighted. The efficacy of the control is weakened by the diversity of legal systems and the obstacle of the language.[15] Posted workers also have difficulty in asserting their rights.

Several decisions (Viking-Line, Laval, Rüffert) by the ECJ have been discussed in regard to the protection of posted workers' rights.[16] Given the opposition on the part of the national parliaments, which used their new prerogatives in terms of controlling subsidiarity, the Commission had to withdraw a text that tried to balance the right to collective action with the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services.

III/ Vital response in support of free movement

These difficulties have to be identified and call for pragmatic response without bringing the greatest achievement of European integration into question. Five areas are concerned.

1/ A single market at the service of the citizens

The revival of the dynamic of the single market should allow both the creation of a framework that will foster the return of growth, re-establish European confidence in integration and respond to the challenge of social cohesion. To this end the Monti report suggested a new strategy for the single market. This was the core of the "Single Market Act" presented by Michel Barnier and adopted in October 2010. The Commission intended notably to develop worker mobility. The goal of a deeper and fairer single market comprised one of the areas in the guidelines put forward by Jean-Claude Juncker to the European Parliament in June 2014. He recalled on this occasion that the free movement of workers was one of the pillars of the internal market that had to be defended whilst acknowledging the right of Member States to counter abuse and stressing that in the Union the same work in the same place should be remunerated in the same manner.

European surveys highlight the impediment created by the diversity of cultures and languages, even ahead of administrative difficulties associated with the heterogeneity of the different social systems.[17] The development of exchange programmes like Erasmus or Leonardo could therefore provide an answer to this.[18] In its working programme for 2017 the European Commission intends to implement the "youth" aspects of the strategy for skills, notably to increase apprentice mobility.

The European Union has also adopted measures to overcome the obstacles to the free movement of workers within the single market. To guarantee the efficiency of the non-discrimination principle a 2014 directive asks the Member States to guarantee migrant workers the appropriate means to appeal against discrimination and to introduce information structures regarding their rights.[19] The revision of the 2005 directive in 2013 on the recognition of professional qualifications led to the creation of a "European professional card" that helped certain professions facilitate the recognition of their qualifications via an e-certificate.[20] The European network of employment services (EURES) provides information in 26 languages regarding the working and living conditions in the Member States and enables access to various job offers. Moreover a directive adopted in 2014 set minimal standards regarding the protection of mobile workers' rights.[21]

2/ A stronger feeling of European citizenship

The feeling of European citizenship has been growing since 2010. 67% of Europeans feel that they are citizens of the European Union. 50% say they know their rights. But 69% want to know more about these rights.[22]

Free movement, seen as the main acquis in European integration, is the centre of the rights attached to European citizenship. Nine Union citizens in 10 know they have the right to free movement. More than 2/3 of them believe that the free movement of people in the Union affects the economy of their country positively.[23] However, as revealed by the public consultation organised in 2012, nearly one in five had encountered problems, often due to fastidious or unclear administrative procedures. Hence the obstacles encountered have to be removed.[24] In its 2013 report on citizenship the European Commission suggested the reduction of red-tape by facilitating the acceptance of identity and residence documents (notably via uniform European documents).

3/ Means to control and regulate migratory flows

European texts give the Member States tools with which to control and regulate migratory flows better. These instruments must be used and improved.

A/ The regulation of internal migratory flows

The extent of European internal mobility remains modest. Work is the main motivation for Europeans who live permanently in another Member State. 78% of those of working age are in work. Their employment rate lies at around 68% ie 3.5% more on average noted than amongst European workers living in their own country. Most mobile workers in the Union (58%) come from Central and Eastern Europe. But their share has declined somewhat in comparison with the period 2004-2008 (65%) to the benefit of workers from countries in the south which are suffering the effects of the economic crisis (18% against a previous 11%). Germany and the UK are the two main destination countries.

- The right to social assistance and social benefits is not unconditional

Access to social assistance by citizens who are not working is the focus of restrictions so that they do not become an excessive financial burden for the host Member State. During the first three months of residence the host Member State is not obliged to provide non-working European citizens with social assistance. Beyond three months and up to five years the Member State can decide not to grant social aid if the person concerned does not meet the required conditions to benefit legally from the right to residency for a period over three months. However after five years Union citizens who have acquired the right to permanent residence can benefit from social assistance according to the same conditions as the citizens of the host Member State.

Regarding social security benefits the Member States set the applicable rules. Benefits, the conditions for them being granted, their duration and the amount paid are defined by the host Member State's legislation. Benefit rights can vary from one State to another. Regulation (883/2004) of 29th April 2004 only guarantees effective social protection mainly by defining which Member State is competent in terms of social security.

In response to the questions set by the Social Court of Leipzig the ECJ deemed that to be able to access certain social benefits citizens from other Member States could only demand equal treatment with the citizens of the host State if their stay respected the conditions set down in the 2004 directive. On this occasion the Court recalled that according to the directive the host Member State is not obliged to grant social assistance benefits for the first three months of the stay. When the length of the stay is over three months, but below five years, the directive conditions the right to stay notably by the fact that economically inactive people must have sufficient own resources. The directive aims to prevent inactive citizens from using the social protection system of the host Member State to finance their means of existence. A Member State must therefore be able to refuse to give social benefits to inactive citizens who are moving freely with the sole aim of taking advantage of the social aid of another Member State, whilst they themselves do not have adequate resources to pretend to the right to stay; each individual case has to be examined without taking into account the social benefits requested.[25]

- Free movement has limited effect on national social security systems

In October 2013 the European Commission presented a report on free movement, drafted on the basis of information communicated by the Member States and a study that it had undertaken. It emerged that the citizens of other Member States did not turn to social benefits any more than the citizens of the host country. Inactive people from other Member States[26] represent a very low share of the beneficiaries. The effect of these benefits requests on national social budgets is insignificant. These people comprise less than 1% of all beneficiaries (Union citizens) in six of the countries studied (Austria, Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Malta and Portugal) and between 1% and 5% in five other countries (Germany, Finland, France, Netherlands and Sweden). The report also shows that spending linked to healthcare involving people from other Member States is marginal in comparison with the rest of healthcare spending (0.2% on average) on a scale of the host country's economy (0.01% of the GDP on average). The Commission's conclusion is therefore that "workers from other Member States are, in reality, net contributors to the public finances of the host country."

- European legislation gives the Member States the tools to counter abuse

The directive of 29th April 2004 provides measures to help counter certain types of abuse. Prior to three months the Union citizen can be expulsed in the event of a serious threat being made to public order, public security or public health or if he/she is an "unreasonable burden on the social assistance system". Limits can be set on the right to stay (art. 45 TFEU). The directive (art. 35) gives the Member States the ability to adopt necessary measures to refuse, cancel or withdraw any right given in virtue of the directive in the event of abuse of the law or fraud, such as marriages of convenience for example. Any measure of this nature is proportionate and subject to procedural guarantees provided for in the directive. In September 2014 the European Commission presented a manual on marriages of convenience indicating how to implement the general principle of proportionality.[27]

The European Commission also suggested measures to strengthen existing tools notably the drafting of guidelines to specify the notion of "usual residency"[28] On 5th December 2013 the Home Affairs Ministers agreed on two things: the freedom of movement is a fundamental right of the citizens of the Union and individual cases of abuse must be countered.

It seems that this dual requirement has to guide the policies to be undertaken in this domain, both at national and European levels. We cannot challenge the fundamental principle, which lies at the heart of European integration and which is largely identified by the Union's citizens as one of its greatest achievements, simply because certain types of abuse have been observed. Conversely, we cannot ignore cases of abuse and we have to counter and prevent them. The Member States are therefore legitimate in acting in this direction as long as they do not diverge from the rules set out in the treaties and by secondary law. A rigorous, regular assessment of European legislation is also a requirement to ensure that the Union's legal framework effectively responds to concerns caused by certain types of abuse in the Member States. This vigilance should also help to prevent risks of division in the European Union.

- The need for European coordination

The consideration of the situation of the Roma highlights that certain problems raised by free movement call for European response and solidarity between Member States. In April 2011 the European Commission asked the latter to submit a national integration strategy for the Roma living in their country on the basis of guidelines defined at European level.[29] The European Commission assesses the implementation of these strategies and makes an annual report. Conclusions provide information for the annual European Semester for the coordination of economic policy, which can lead to specific recommendations being made per country regarding the Roma question. In 2013 five Member States (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia) were given recommendations regarding their national strategy and the need to guarantee Roma children access to high quality schools that fostered integration.

B/ The regulation of external migratory flows and the strengthening of internal security

Free movement is inseparable from the measures that were introduced to guarantee security within the Schengen area. Cooperation and coordination between police and the judicial services have been strengthened. These measures are said to be "compensatory". From the start safeguard clauses were provided for, allowing the States to re-introduce border controls in two situations: in the "event of a serious threat to public order or internal security", in the case of foreseeable events such as an international summit, like the G20 or a major sports or cultural event. Following the Franco-Italian request in April 2011, drafted in the context of the "Arab Spring", the Schengen border code was modified to allow the re-introduction of controls as a last resort, for a limited period (6 months renewable up to two years) in the event of serious, continued problems on one of the external borders. On this basis the Council authorised five Member States to re-introduce temporary controls.

Each Member State takes responsibility for the control of its external borders (nearly 50 000 km, 80% of which are in a maritime area) for all of the other States. This is why mutual confidence is vital. This is the issue at stake in a truly effective assessment mechanism. Revised in 2013 it gives a greater role to the Commission. Surprise visits are possible. Assessments can be thematic and regional. These assessments involve experts and the States in question.

Given the refugee crisis a European border and coast guard was created with Frontex on 6th October 2016. A rapid response pool of 1500 border and coast guards has been established. A pool to keep illegal immigrants and the smugglers out has been established.

Moreover the Schengen border code is being modified so that systematic control on the external borders can be organised - entry and exit alike - including for European citizens. A political agreement was found between the Council and the European Parliament in December 2016. This modification provides for the obligatory consultation of European databases - the SIS and also the Interpol file - as well as national databases. The interconnection of files would be a guarantee for greater efficacy but the issue is still being debated.

In April 2016, the European Commission suggested the establishment of an entry/exit system to strengthen the efficiency of controls and to identify those who abuse their right to legal residency in the Union. This system would enable the monitoring of flows and would be used in the fight to counter terrorism.

The creation of a European Travel Information Authorisation System (ETIAS) suggested in November 2016 by the European Commission should lead to the collation of information on all travellers coming to Europe as part of an obligatory visa exemption regime and enable the detection of possible security problems before people travel to the Schengen area.

In December 2016 the Commission presented measures designed to improve the use of the Schengen Information System (SIS), the sharing of information and cooperation between the Member States, notably by introducing a new category of alerts regarding "unknown wanted people" and full access rights for Europol. They will contribute in the fight against terrorism by establishing the obligation to create an SIS alert in affairs linked to terrorist crimes and a new "in depth control" to help the authorities collate vital information. They will help in the effective implementation of entry bans on citizens from third countries by making their introduction into the SIS obligatory. They will also facilitate the execution of return decisions taken against illegally resident third country citizens by introducing a new category of alerts for return decisions.

To establish solidarity between the Member States a relocation mechanism was planned for. It was supposed to cover 160,000 asylum seekers for the countries in which there had been a massive influx of people i.e. Greece and Italy. But this relocation mechanism finally only covered 8000 asylum seekers. At the same time the Union wants to strengthen cooperation with third countries of origin and transit, in line with the La Valette Summit that took place in November 2015. In June 2016 the High Representative and the Commission suggested a new partnership framework with third countries that was approved by the European Council. Five priority countries were concerned (Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal). With a first assessment in hand the European Council stressed that this new framework was a major tool in countering illegal migration and its in depth causes, particularly regarding the route to the Central Mediterranean. Moreover the introduction of an external investment plan presented as the external chapter of the investment plan for Europe aims to stimulate investment and the creation of jobs in Africa and in neighbouring countries in the south and east of the European Union.

4/ Protection against the risk of social dumping

Free movement must not create conditions for fraud that fosters social dumping. The implementing directive 2014/67 of 15th May 2014 helps specify the implementation of the directive 96/71 regarding posted workers, to prevent fraud. The host Member State can oblige a foreign company which posts workers in its territory to take a specific set of steps, such as the obligation to declare and retain the same work contract for the entire duration of the posting. Since this list is open the Member States can introduce other measures by informing the European Commission. A joint liability mechanism of the contractor and his direct sub-contractor is provided for in the building trade. A Member State can extend this mechanism to other sectors. However, the principle of affiliation to the social security regime of the country of origin has not been challenged.[30]

On 8th March the Commission presented a draft directive designed to define better conditions for the posting of workers. It meant highlighting the principle of "equal work, equal pay at the same place of work".[31] The proposed revision focuses on remuneration, the length of the posting, sub-contracting chains and the use of temping agencies. The main modification focuses on the salaries to which posted workers have the right. The present directive only demands that posted workers receive the minimum wage. The proposals provide for the application of the same rules regarding remuneration in force in the host Member State, in line with the law or the generally applicable collective conventions[32] The ECJ clarified in 2015 posted workers' rights notably stipulating the factors that had to be integrated into remuneration.[33] It considers that participation in public procurement could be subordinate to a commitment to pay the minimum salary, notably when a sub-contractor is being used.[34]

In December 2016 the European Commission also proposed a review of the Union's regulation on the coordination of social security regimes. Its proposal provides in particular for the tightening of administrative rules regarding the coordination of social security for posted workers. This means providing local national authorities with the necessary tools to check on workers' status. Clearer procedures would be established for cooperation between these authorities to counter potentially unfair or abusive practices. This proposal does not plan however to modify the present rules governing the export of family benefits. The country where the parent or parents work remains responsible for the payment of family benefits, and this amount can only be modified if the child lives elsewhere. According to the Commission less than 1% of family benefits are exported from one Member State to another in the Union.

5/ Economic and Social Convergence

Over the last decade mobility from the new Member States represented ¾ of the total increase in the number of citizens mobile in Europe.[35] Post-enlargement mobility has had positive effects: intra-European mobility is helping rebalance competences and jobs. Two million jobs remain vacant in the Union in spite of the economic crisis. 73 million jobs should be available within the Union by 2020, given the number of people who will be retiring. This raises the issue of a truly European labour market that is far from complete.

This positive approach in terms of mobility must not lead to us ignoring the difficulties that can arise on three levels. From the point of view of the host country migration must help fill vacant jobs and therefore attract the skills needed for the national economy to function. From the point of view of the emigration country mobility must not lead to a departure of vital, qualified forces to the detriment of internal economic requirements. From the EU's point of view mobility must not mean increasing concentrations of qualified labour in parts of the common area which are already the most economically advanced. Free movement must not therefore be dissociated from a global approach that focuses on the mutual benefit that it provides for the Member States. It must go hand in hand with the progressive completion of economic and social convergence.

[1] Standard Eurobarometer Survey 83, Spring 2015 - TNS Opinion & Social.

[2] Court of Justice, 17th September 2002, Baumbast, aff. C-413/99.

[3] Directive 2004/38/CE 29th April 2004 on the Union's citizens' rights and those of the members of their family to move and stay freely within the territories of the Member States.

[4] More than 188 million Europeans (37% of the total population) have a European health insurance card that enables their right to health services which they might need during a temporary stay in another country of the Single Market.

[5] Controls on the internal borders were first abolished between Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Portugal in 1995. The Schengen Area then progressively extended. It now comprises 26 countries of which 22 are Union Member States.

[6] Mario Monti : A new strategy for the single market at the service of the economy and European society - Report to the President of the European Commission 9th May 2010.

[7] Single Market: awareness, perception and impact, special Eurobarometer survey 363, Nov 2011 - TNS Opinion and Social.

[8] Eurostat, January 2017.

[9] UNHCR, Regional Bureau Europe, Weekly Report, 23rd December 2016.

[10] "Free movement needs to be less free", Financial Times, 27th November 2013.

[11] Cf. Sébastien Richard: "The management of posted workers in the EU", European Issues n° 300.

[12] Johan Rochel: " Libre circulation : ou quand le vote suisse fait trembler l'Europe ", in L'opinion européenne in 2014 Editions Lignes de Repères, 2014.

[13] More recently it was possible to plot the journey taken by the perpetrator of the Berlin attack on 19th December 2016, from Berlin to Milan (via the Netherlands and France) where he was finally neutralised.

[14] " Sébastien Richard : "The management of posted workers in the EU" European Issue, n° 300

[15] Information Report by Gilles Savary, Chantal Guittet and Michel Piron on the draft directive on the implementation of the directive on posted workers. National Assembly n° 1087, May 2013.

[16] Viking-Line Decisions 11th December 2007, Laval 18th December 2007, Rüffert 3rd April 2008.

[17] Special Eurobarometer survey 337 - Geographical mobility of labour, November-December 2009.

[18] Cf. Yves-Emmanuel Bara, Maxence Brischoux and Arthur Sode: What mobility for labour in Europe, Trésor-Eco, n° 143, Feb. 2015.

[19] Directive2014/54/EU 16th April 2014 on measures facilitating the exercise of rights given to workers in the context of the free movement of workers.

[20] Directive 2013/55/EU 20th November 2013 modifying the directive 2005/36/EC on the recognition of professional qualifications and regulation (EU) n ° 1024/2012 regarding administrative cooperation via the internal market information system ( IMI regulation).

[21] Directive 2014/50/EU 16th April 2014 on minimal prescriptions aiming to increase worker mobility between the Member States by improving their acquisition and protection of additional pension rights.

[22] Standard Eurobarometer Survey 83, Spring 2015 - TNS Opinion & Social.

[23] Standard Eurobarometer Survey 79 / Spring 2013 - TNS Opinion & Social.

[24] European Commission: "2010 Report on Citizenship in the Union", 27 October 2010, COM(2010) 603 final.

[25] ECJ decision 11th November 2014 Elisabeta Dano, Florin Dano c/ Jobcenter Leipzig (case C-333/13).

[26] They represent a very low share of the total population in each Member State and between 0.7% and 1% of the Union's total population.

[27] Communication COM (2014) 604 final 26th September 2014.

[28] Free movement of Union citizens and members of their family: five cases to make the difference, COM (2013) 837 final.

[29] European Union framework for national integration strategies for the Roma for a period up to 2020, 5th April 2011, COM(2011) 173 final.

[30] Sébastien Richard: the implementing directive on posted workers: and what now? European Issue n° 383, 19th February 2015.

[31] 7 government (Germany, Austria, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Sweden,) promoted this principle in a letter addressed on 5th June 2015, the European Commissioner for Employment, and Social Affairs, Marianne Thyssen, which called for a revision of the 1996 directive.

[32] Information report by Eric Bocquet : "Locating posted workers' rights in the host country" Senate n°645 (2015-2016) 26th May 2016.

[33] Decision of12th February 2015, case C‑396/13, Sahkoalojen ammattiliittory/Elektrobudowa Społka Akcyjna.

[34] Decision of 17th November 2015 RegioPost GmbH & Co. KG against Stadt Landau in the Pfalz.

[35] European Commission, January 2014.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Institutions

Elise Bernard

—

17 December 2024

Africa and the Middle East

Joël Dine

—

10 December 2024

Member states

Elise Bernard

—

3 December 2024

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierre Andrieu

—

26 November 2024

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :