Economic and Monetary Union

Charles de Marcilly

-

Available versions :

EN

Charles de Marcilly

The European Union is one of the main economies on the planet representing 17% of the world's wealth. The leading consumer market, via the average purchasing power of its 500 million citizens, it exercises an exceptional force of attraction. 55% of America's foreign investments are directed towards it and it remains the leading export market for more than 80 countries. Its citizens draw benefit from it since 30 million jobs depend directly from the EU's external trade.

However economic trends are causing a degree of uncertainty, as international trade growth stagnates at around 2.7%; in 2016 it is forecast to be at its slowest since the financial crisis[1]. World growth is still lukewarm according the IMF[2] data, and the European Central Bank regularly expresses its concern about the euro zone's modest growth forecast. Moreover, thanks to deeper integration, trade and finance enable the development of globalisation which is reflected in the tripling of world trade since the 1990's. However, since its creation in 1995 the WTO has also witnessed a threefold increase in anti-dumping procedures or "temporary barriers" thereby revealing protectionist measures[3]. The limits being place on trade are worrying. The G20 members - representing 85% of the world's wealth - have been obliged to reassert their "opposition to all types of protectionism from the point of view of trade and investment" whilst many sectors - steel being the most emblematic - suffer from globalisation that is deemed as being imposed.[4]

However, the European Union draws on the development of the agreements that it concludes with more than 140 partners[5]. Aware that 90% world growth will be outside of the Union in 15 years' time (according to the IMF), Europe is trying to promote privileged trade relations, and at the same time develop its standards and values[6]. To do this it now has to win over public opinion. But this is not the only challenge to which it has to rise. We can pin point four others: clearing the ambiguity between opening and protection, establishing robust defence instruments, managing complex ratification processes, and British uncertainty. Without any clear answers to these questions, in the future trade standardisation might be forced upon it together with norms that are lower than those of its model and its aspirations. Will the challenge over the next few months not be to show that the European Union can make globalisation more acceptable[7]?

A/ More comprehensive agreements - a cause of concern

a. Modification of the balance of power

The suspension in 2008 of the WTO's Doha Round can be explained amongst others by two changes. The first is the acceleration of certain economies which between the start of the discussions at the beginning of the 90's and the formal rounds have progressed significantly. China and India can no longer be classed as developing economies or emerging countries. The applicable rules have to be adapted according to the development in size and capabilities of the players or they may become obsolete as they offer unjustified advantages. The second development involves the upheavals in the economy that are not just focused on the goods trade. This means integrating new economic areas in the agreements (services, new technologies, investments, public procurement, competition, intellectual property rights, sustainable development ...). Also known as the "four questions of Singapore[8], issues linked to investments or public procurement face structural obstacles under the WTO.

This does not just concern the rules governing goods and customs duties, but it means widening the agreements to intellectual property issues and patents. The growing complexity of the chain of values, together with the emergence of economic giants, which are no longer "emerging", make a full agreement with more than 160 players highly unlikely.

b. A doctrine focused on "minilateralism"

In this context, since there is not enough progress being made with all 160 WTO members, the European Union has drawn up a new approach, based on bilateral or regional trade agreements. Hence a new generation of comprehensive free-trade agreements extending beyond tariff reductions and the trade of goods (EU-South Korea, Peru and Colombia) have now been made. It also promotes agreements with a reduced number of partners, like the agreement on the trade of services (Trade in Services Agreement-TISA) under negotiation at present by 23 of the Organisation's members.

In 2010 the Commission presented a communication entitled "Trade, growth and world affairs"[9] making international trade one of the pillars of the new Europe 2020 strategy[10]. In line with this, the new strategy "trade for all" defines trade as the main driver of growth and the creation of jobs, and also recognises the need for a coordinated approach to both internal and external policies. The development of this strategy is based on four pillars which are transparency, efficiency, including the so-called "last generations" issues, the promotion of values and the extension of the negotiation programme by deepening existing bilateral agreements redefined under a multilateral framework, i.e. the WTO.

Historically and conceptually customs rights and tariff barriers have gradually been surpassed[11] by the need for regulatory convergence. The declared goal is to strengthen regulation cooperation and to define international standards. By doing away with regulatory red tape, free-trade agreements (FTAs) would allow both sides to aspire to better standards - in the area of the environment for example - with the aim of becoming points of reference.

The European Union, a normative power, has the arms with which to impose its collective preferences, but it must not miss out on regional agreements. This means defining standards that will be prescriptive, since they will be unavoidable in terms of their weight on the markets. Some even believe that the transatlantic agreements comprise the last chance we have to ensure that globalisation continues according to western values. According to this analysis the first goal of the negotiations with the USA would be to "re-assert transatlantic leadership so as to shape a new international economic system."[12] This approach is based on different axes and the strategies of the main blocs would adapt according to progress made in negotiations over the transpacific or transatlantic agreements. This means that beyond the traditional "trade giants", emerging countries in the international trade arena are trying to assert themselves rapidly as unavoidable partners. This is, for example, the case with the ASEAN,[13] Mercosur[14] and the Pacific Alliance[15] countries. The USA has already taken the initiative to strengthen their economic and trade ties with the countries of South and Central America, as well as with several emerging countries in Asia. The European Union's goal is not to get left behind and to remain a normative power[16].

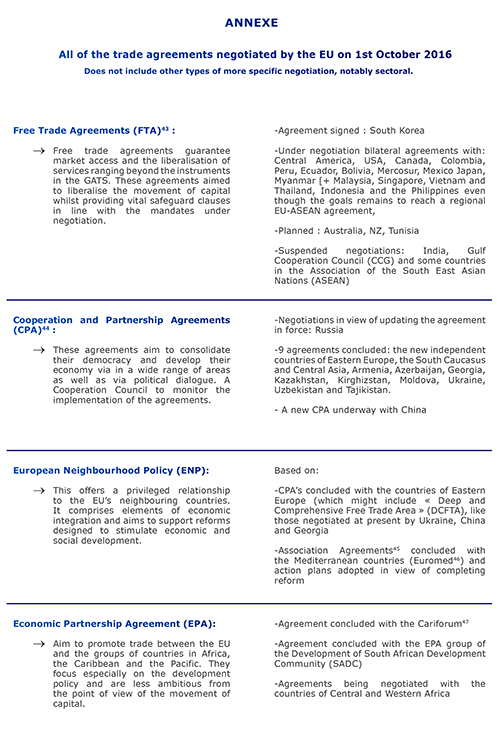

The results are there to be seen. On 1st October 2016, the European Union had 30 effective agreements including 60 partners, 7 were about to be concluded with 31 countries and 20 were under discussion, including those with Canada (CETA) and the USA (TTIP), but also with Japan, Mercosur, Tunisia, Indonesia and the Philippines.

The European Union probably offers the most protective model in terms of social, individual and collective rights. It mobilises 50% of world spending on healthcare and solidarity. This model has not been copied elsewhere and will probably not be exported. In spite of the reassuring declarations made by American Secretary of State John Kerry[17], European citizens fear regression, notably regarding social and environmental standards. One of the issues at stake is therefore to convince the latter that the Union is likely to see the conditions of most trade partners rising and not a decrease in its collective choices.

c. Promoting upwards harmonisation

On reading the fears and concerns expressed by some parliaments and representatives of civil society, the main fear that emerges is that European standards and norms will be harmonised downwards. Although we must not be naive, the feeling of having a defensive approach to trade and being a "losing" Union has to be tempered - on the public face of things at least. Indeed legally, and all the more from a political point of view, negotiators cannot discuss standards that would be lower than those in force within the European Union. Politically the legislator would not allow the regulator to encroach on his prerogatives. The mandates granted to the Commission are explicit. Moreover in a context of a balance of power between the parties involved and with the evident will for upward harmonisation the European Union systematically tries, under the framework free trade agreements, to spread its model and its own collective preferences. The addition of chapters devoted to sustainable development, social impact and consumer protection, discussed with some countries, which have not thought of these things, enables the promotion of a European vision. Regarding these issues surveillance committees have been created even though it is regrettable that they are only advisory.

The Commission's proposal for a new judicial system regarding litigation settlements between investors[18] that was presented in September 2015 underscores its strength of proposal. The European Union offers an alternative to a system that has been paralysed for the last 40 years, whilst European investors have had to turn to it more in the last decade[19].

Moreover, with the exception of the so-called "second generation" agreements negotiated with the USA, because it goes beyond the area of customs and tariff barriers, open or concluded negotiations are underway with powers that are much weaker than the European Union. The balance of power therefore still lies with the 28 Member States as they assert their collective weight as world's second export force and also as an internal market with a potential of 500 million consumers

B/ 5 Internal Challenges

a. Settling ambiguity: opening and concern

And yet globalisation is disrupting the established order, destabilising governments and public opinion, and for some, it means regression in terms of world governance. This concern is not just to be found amongst Europeans, and the States that are traditionally supportive of free trade are now promoting a more rigid line, which has been evident in the American presidential campaign both amongst the Republicans and the Democrats.

The Eurobarometer study shows how the position and questions put by European citizens regarding globalisation, trade and free-trade have developed over the last ten years.

In the spring of 2007 European opinion largely preferred free-trade to protectionism, in spite of the rumblings of the future crisis. Between 2007 and 2009 the number of people who considered free trade positively remained stable, totalling 77% (only 17% viewed it negatively). To be more precise, those supporting "protectionism" were mostly to be found in the Mediterranean countries[20] to which we might add Romania, Luxembourg and Ireland. Opinion was more divided in Italy and Slovenia, whilst Hungary and Slovakia clearly rejected protectionism by 78 and 79%. However in 2009 the younger generations tended more towards a positive view of protectionism (43% amongst the 15-24 year olds).

Paradoxically globalisation, as an opportunity for economic growth, was supported by 59% of the citizens in the autumn of 2009, but this was especially the case with 70% of students. The views of globalisation and that of free-trade do not therefore necessarily follow the same curve. Although Europeans generally, and young people in particular, agree that opening to the rest of the world is necessary to growth and that it is potentially beneficial, they fear that non-European economic agents will be a factor of instability because of their supposed superior ability to impose their rules on the game in terms of relocation, standards and investments.

This ambiguous scenario is confirmed with the Eurobarometer of the spring 2015: it indicates that positive ideas about the economic aspect of globalisation was rising amongst European public opinion for the third time since it was the case amongst 57% of Europeans. The difference between positive and negative opinions regarding the economic role of globalisation lay at a record level of +29, ie the highest level since 2010. In the same vein we note that negative ideas of globalisation were still only a majority in Greece (62%) and Cyprus (50%)! The traditional "pro-globalisation" countries are still Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, Malta, Finland, Germany and Ireland. The opinion ratio is however tighter in France, Belgium and the Czech Republic. But the acknowledgement of benefits or of the inevitable nature of the globalisation of trade does not match support to the free-trade agreements negotiated by the EU. This highlights the total ambivalence of citizens' positions regarding international trade: the recognition that growth will come from outside, but a fear of a weakening in European standards[21].

b. Media coverage - a source of paralysis

Peter S. Rashish notes that "a great share of opposition to the TTIP comes from a trend amongst public opinion to confuse globalisation with trade policy."[22].

In the European Union we note a contrast between the free-trade supporters and a more protectionist approach, carried along by concern and even a political agenda. The former are quite discreet basing themselves on the inevitable nature of globalisation, which is no longer a pertinent argument. The latter however rely on a strong, significant ability to mobilize. The Votewatch Institute[23] studies the main votes in the European Parliament on free trade agreements over the last two years and it notes that MEPs mainly voted according to their national political family. However in 2012 this tradition changed. The rejection of Acta[24] illustrated the sensitivity of MEPs to public opinion in opposition to their party and their government, since they largely rejected an agreement that had been approved by 22 governments out of 27.

The influence of communication is evident if we look at public opinion and its perception of the agreement negotiated specifically with the USA.[25] Between November 2014 and May 2016 European support to this agreement clearly slowed, dropping by 7 points. The level of support dropped sharply in response to campaigns undertaken by opponents to the agreement. At the same time the number of citizens opposed to a free trade agreement and investment between the EU and the USA rose from 25% to 34%, i.e. a rise of 9 points between 2014 and 2016. The structure of the opposition to the FTA also changed. Between November 2014 and May 2015 support to an agreement declined in 14 States with contractions of over 10 points in Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands. The latter three countries are incidentally those which for a long time experienced difficulty in supporting the agreement made with the Canada. Yet all of the Member States renewed the European Commission's mandate for the transatlantic partnership in June 2016.

It also appears that not only do certain States block the agreement (or speak of the possibility of doing so) to modify it, but they also do this in response to their public opinion. This political approach undeniably influences the ability to negotiate, and it also affects collective credit. During debates over the agreement with Canada in September 2016, several MEPs questioned the image being portrayed and the ability to conclude agreements with other less moderate powers.

Since the European Parliament has the power to reject a finalised agreement, communication with the citizen is therefore one of the crucial issues at stake in trade policy. The possibility of including national parliaments will only accentuate this phenomenon. It would be extremely difficult to promote agreements that had been supported discreetly during the mandate, then approved once negotiated via parliament, given the mobilisation of their opponents. In response to the failure of ACTA, the institutions now communicate more than ever before to explain almost in real time what is on the negotiation table. Being attuned with public debate has become one of the imperatives in order to achieve support for negotiated agreements. Live press conferences on the internet, meetings with citizens, NGOs and businesses - never before have negotiations with Canada and the USA been the focus of as many explanations and debates. This new state of affairs in terms of communication was also announced the in "trade for all" strategy. Many texts are also available to the public. The 1600 pages of the CETA agreement are online and the TTIP is available on the sites of some NGOs. However the demand for transparency, albeit legitimate, also seems to be a means to blocking the agreements more than to amending them.

The same applies to potentially confusing positions. Indeed some governments do not defend publicly what they support in Brussels and use the trade agreements to domestic political ends, and even for their own electoral strategies. Finally, some parties use trade as a divisive issue, as was the case in the Netherlands, when on 6th April 2016 there was a referendum on the Association Agreement between the EU and Ukraine in a tense geopolitical context. Because of a new law that enabled 300,000 signatures to ask for a referendum on a parliamentary vote, a new political opportunity was provided by the association agreement. The supporters of the "no" vote did not campaign on the question asked, but used it as a symbol of the European Union. Citizens had the impression that the question asked was secondary, and questions, misconceptions and fear linked to the European project were expressed during this vote. Only 38.21% voted "yes" to this popular consultation in which only 32.8% of the Dutch turned out to vote.

However trade negotiations undertaken by the Commission are done so on the basis of mandates. The latter are supported unanimously by the Member States and should undergo the same procedure to be withdrawn. Although the Commission asked "trade for all" for the declassification of all mandates (ie to make them public) in its communication, only three were declassified by the Council (USA, Canada and services TiSA)).

As noted by the British Parliament "the traditional political obstacles to trade agreements lie in the fuzzy nature of the potential advantages put forward, whilst the costs are concentrated."[26] Transparency cannot just be a political end, it must retain its pedagogical virtue. Negotiations and even more so, second generation agreements, are the focus of arbitration between various chapters covering distinct sectors of activity. The Commission and the governments must also work together to organise responses and explanations given to legitimate questions raised by civil society.

In the eyes of the trade partners it might seem impossible to negotiate with a Union whose fragmentation makes the hope of concluding an agreement too precarious. In the future the public inclusion of MEPs and national MPs in the negotiation mandate seems all the more necessary with the diversity of certain agreements.

c. Showing its ability to protect itself by using adapted instruments

In just one decade the financial crisis and changes in economic power balances have increased the need to act collectively at European Union level. However national perceptions and choices regarding third countries often seem contradictory. Historic relations, geography or trade balances vary, which leads to blockages or inadequate response. European problems in adopting a strong position in order to define which status to give China are an illustration of this. The enthusiasm which prevailed in 2001 when China joined the WTO, with the possibility of it being granted the status of market economy following a transitional period of 15 years, now seems defunct. These outdated views of the emerging economies, which have become giants in one decade, but without wanting to adapt their common behaviour[27], force us to rethink trade relations, notably in a defensive way. Jean-Claude Juncker stressed this in his speech on the State of the Union on 14th September 2016, "we must not be the naive supporters of free trade, but capable of responding to dumping with the same firmness as the USA." This is why the Commission is calling for rapid support to proposals in order to step up trade defence instruments that date back to 2013, whilst 12 States are still against it[28]. This wait-and-see attitude will not go without consequence since the European Union - the third user of trade defence tools in the world - might possibly deprive itself of 90% of its anti-dumping measures, if it were forced to modify its methods of calculation[29]. The European Commission will present proposals in November to strengthen the Union's trade defence system. The response given by the Member States will be a good measure of its will to act in an orderly fashion against abusive behaviour, in the ilk of measures taken in competition law.

d.Diversity: the Challenge to Ratification

Trade policy has been federalised since the Rome Treaty in 1957. The Union's exclusive competence[30], which went mostly unchallenged for several decades, now seems to be under the fire of increasing criticism, with growing media coverage of the free trade agreements. This is encouraging several States and Parliaments to ask for more cooperation.

An international agreement is said to be "mixed" when it involves one of the areas in which the European Union shares competences with the Member States, (article 4 TFEU). In this case the agreement is concluded both by the EU and by the Member States, which have to give their greenlight.

After the conclusion of negotiations in the EU-Singapore agreement in October 2014[31], the idea that trade agreements were the sole competence of the EU was brought into question. Out of concern for clarity and legal security the Commission called on the opinion of the Court of Justice regarding the nature of the EU-Singapore Agreement.

For their part the Member States want formal participation on the part of the national parliaments. During a Council meeting, conclusions state that national delegations deem the Singapore or Canadian agreements to be mixed. In their opinion the content of the agreements involves shared, if not exclusive, competences[32]. As stressed by the Commissioner Cecilia Malmström in answer to the European Parliament on 19th May 2015, the Court's opinion regarding the mixed nature or not of the EU-Singapore agreement should be noted. This will decide the follow-up to negotiations and the ratification process of the agreements with Canada (CETA) and as an extension of this, the agreement under discussion at present with the USA (TTIP) and also any upcoming negotiations.

Pending the Court's conclusions the Commission legally deems its competence to be exclusive in terms of negotiating agreements, including in the controversial chapter of investments. However the agreement negotiated with Canada highlights the problems linked to the unanimous ratification of such agreements by the Member States and national parliaments. The danger is that trade agreements will be polarised under the threat of veto and contradictory approaches which will accentuate citizens' apprehension and fear. Debates focus on de facto opposition and less on specific modifications, which have generally been integrated in the exceptions during the mandate. Indeed on 23rd September Trade Ministers unanimously supported the agreement with Canada, the first to be concluded with a member of the G7[33]. However in the weeks and months prior to this several States threatened to veto 7 years of negotiations for various reasons: Austria over the arbitration tribunals, Romania and Bulgaria over the non-suppression of visas for their citizens and Belgium because the support of the Walloon parliament - ie 0.7% of the European population - was vital to the federal government.

This case illustrates how difficult it is to obtain unanimity with the national parliaments, independently of the traditional diplomatic games that reoccur in each negotiation. Under the free trade agreements the European Parliament represents the citizens during a vote of support or rejection. This competence, which was strengthened by article 281.6 of the Lisbon Treaty, comprised real progress in the support given to negotiations (thanks to non-legislative but politically far reaching resolutions) with the threat of veto if attention was not paid to them. Moreover the unanimity rule of 38 national parliaments raises the issue of conflicts in democratic legitimacy: one national Parliament representing less than 1% of the European population can reject an agreement supported by 37 others.

In short the mosaic of positions, goals and national interests have to agree with each other, whilst the Commission has worked for several years on the basis of a mandate given by the governments of each Member State! Underpinned by a feeling of general indifference at the beginning of the process, the bitterly negotiated agreement, must, once it has been concluded with the other party, be the focus of debate and clarification. Under the mixed agreements the ratification process is very much like an army assault course. Each country, each parliament, and even each political majority, has its own interest. This process can but lead to blockages or multi-tiered agreements - by withdrawing the application of chapters from certain territories in order to remove obstacle, an option which is politically and legally questionable - and contrary to the European spirit. This will be all the more problematic if the States and the European Parliament approve negotiations; the treaty will be implemented temporarily as long as all of the national parliaments have not approved it: this truly is a Damocles sword and comprises a loss of collective credibility in terms of promoting European interests in world trade. This option was privileged for the agreement with Peru but in a different situation[34].

Transparent debate during the attribution of negotiation mandates to the Commission and support on the part of national parliaments would improve the democratic chapter of attribution of this competence and strengthen political support to collective negotiations. This means opening and politicising debates regarding mandates for a facilitated ratification afterwards. This approach would help reduce the risk of another "Acta" that was negotiated for several years before being rejected by the European Parliament following strong mobilisation on the part of the citizens.

e. British uncertainty is weakening the trade bloc

The result of the British referendum of 23rd June 2016 will have implications. The UK which is the EU's second economy, representing 15.4% of the GDP in 2014, but especially 12.9%[35] of its world goods exports and 21.3% of its services exports to third countries in 2015, it is one of the engines behind the community's economy. Its history, its privileged links with certain parts of the world, its "hinterland", its financial market, its natural access to the Anglo-Saxon world are evidence of a discrete trading position within the 28. Its presence on the Single Market is a vital asset for third States, as stressed by the American President, and the Japanese and Chinese Prime Ministers when they visited Europe during the British referendum campaign in 2016[36]. The amputation of its second biggest economy will inevitably be costly to the Union, and also restricting access to its leading market will be painful for the UK.

Hence the implementation of the slogan "taking back control" will be a path full of pitfalls for London and the bearer of uncertainty, both for the Europeans as well as its partners.

The appointment of Liam Cox to the newly created position of International Trade Minister confirms the clear, so often repeated wish to negotiate bilateral trade agreements once the divorce with the EU has been confirmed. World trade is therefore one of the Brexiteers privileged paths, since they believe that alone they will be able to negotiate better agreements than the 28 as a bloc, which represents 20% of the world's GDP however[37]. Although at this stage we do not know what the UK's exit from the European Union will look like, according to the Brexiteers the weight of intra-European trade will condition the joint need for a "soft Brexit". Foreign Affairs Minister Boris Johnson gladly recalls that the UK is a consumer of French wine and German cars[38] and is counting on mutual goodwill to avoid too much disruption in terms of trade balances. As part of the "divorce" negotiations the choices made by the national government in their calculations will carry a risk in terms of their selfish interests and their individual trade balances[39]-, or whether they opt for a collective solution. 45% of British exports go to the internal market and comprised for example a trade surplus of 12.3 billion €[40] for France and 51 billion for Germany[41] in 2015, which will certainly be amongst the issues discussed in terms of the post-Brexit scenario along with access to the Single Market. Is this in the collective interests of the 27 in the long term however?

Legally trade is the Union's exclusive and the UK is tied by negotiations with third parties. The latter is finding it difficult to put together experienced teams of negotiators for a competence that has been devolved to Brussels for several decades[42]. However from a political point of view the message that has been sent out is based on the wish to start post-Brexit agreements. Although Jean-Claude Juncker firmly recalled his prerogatives on the side lines of the G20, it remains that the British government is planning rapid negotiations with third countries without putting forward any specific timetable for this however.

Uncertainty is leading so certain difficulties the first of which is legitimate doubts raised by trade partners over the scope of the agreements that are under negotiation at present. A slowing in ongoing negotiations cannot be rule out. Can we negotiate an agreement as 28 which will only apply to 27? The result has been a certain amount of suspicion about the position adopted by the British in the trade negotiations. Clearly demonstrating national preference, the latter - like any other Union Member - has access to all ongoing discussions with third parties. Finally, if in an optimistic hypothesis the UK does leave the Union by the end of 2019, it still retains its voting rights within the Council, and therefore its right to veto, which raises a Damocles sword over all of the agreements now under discussion. In these circumstances clarification by the British is vital if we are to avoid a harmful blockage to the European Union's ability to drive forward world trade.

Conclusion

Because there has not been any significant progress under the WTO, the EU is trying to strengthen its privileged relations with many countries. This prerogative as an exclusive competence is contested. The so-called new generation agreements, which enjoy wider scope, have mobilised civil society more than in the past. Of course Europeans understand that globalisation is a source of growth, but they fear that their standards will be eroded downwards. Independent of any diplomatic conclusions, convincing the European citizens will determine their support, which is now vital in order to deepen these agreements. In addition to this, and following the British referendum, clarification of Europe's collective goals in terms of trade will be a factor in the discussions launched in September 2016 regarding the future of the European project. As far as the trade chapter is concerned the transparency of negotiations and the promotion of certain values - which are both vital - are not a guarantee for maximum efficiency in negotiations, or for a maximum extension of the agreements. Conversely, with the rise of parallel trade axes, the Union must act together if it is to remain a privileged and unavoidable partner. Above all this is about the credibility of a prescriber of standards and of promoting its collective preferences.

[1] World Trade Organisation, " World Trade Statistical Review " 27 September 2016. In 2017, growth will lie between 1.8% and 3.1%, against 3.6% forecast in the last estimation.

[2] IMF, "World Economic Outlook", 19 July 2016

[3] Jean-Pierre Robin, " globalisation has already dropped down a gear ", Le Figaro, 3rd October 2016

[4] Press release by the G20 leaders at the Hangzhou Summit 4th and 5th September 2016

[5] Jan-Claude Juncker, " The State of the Union 2016 ", 14 September 2016

[6] Data published in "Trade for all : Commission presents new trade and investment strategy", European Commission , 2015, p. 8

[7] Antoine d'Abbundo, " Peut-on rendre la mondialisation acceptable " La Croix, 21st September2016

[8] Four questions were added to the WTO's work programme at the Singapore Ministerial Conference in December 1996: trade and investment, trade and competition policy, transparency of public procurement and the facilitation of trade. (Source : WTO)

[9] European Commission, "Trade, growth and world affairs. The trade policy at the heart of the Europe 2020 strategy", 2010

[10] Parlement européen, " L'Union européenne et ses partenaires commerciaux ", 2016

[11] P Lamy "What future for European Union in World trade" Schuman Report 2014 p.99

[12] Peter S Rashish, " Le partenariat transatlantique, dernière chance pour une mondialisation à l'occidentale "in Annuaire Français des relations internationales, 2016, Université Panthéon-Assas p. 487-497

[13] Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia

[14] Argentina, Brasil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela

[15] Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Chile

[16] On this point the trade agreements take on a geopolitical and not just an economic dimension. See Leveraging Europe's international economic power, Guillaume Xavier-Bender, GMF, March 2016

[17] Speech by John Kerry, German Marshall Funds, Brussels, 4th October 2016

[18] Press release, " La Commission propose un nouveau système juridictionnel des investissements dans le cadre du TTIP et des autres négociations européennes sur les échanges et les investissements ", 16 sSeptember 2015

[19] Eoin Drea, TTIP infocus, Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, April 2015, p.12

[20] Greece (73% against 25%), Cyprus (79% against 15%), Malta (53% against 19%), Portugal (52% against 29%), Spain (48% against 40%)

[21] By presupposing that European are superior to those of our trade partners which should be relativized.

[22] Peter S Rashish, " Le partenariat transatlantique, dernière chance pour une mondialisation à l'occidentale "in Annuaire Français des relations internationales, 2016, Université Panthéon-Assas p. 487-497

[23] Doru Frantescu, "Who is for and against free trade in the European Parliament", VoteWatch, 19th September 2016

[24] Following the first ever direct lobbying by thousands of Europeans via demonstrations in the streets, emails, telephone calls to MEPs, the anti-counterfeit trade agreement (ACTA) was rejected by 478 votes against 39 in support and 165 abstentions on 4th July 2012.

[25] Eurobarometer standards (82, 83, 84, 85) on the issue "what is your position on the free trade agreement and investment between the EU and the USA?" November 2014/May2016

[26] House of Lords, May 2014, quoted by Eoin Drea in The State of the Union, Schuman Report 2016

[27] " Octroi du statut d'économie de marché à la Chine : quelles réponses politiques face au carcan juridique ? ", Charles de Marcilly, Angéline Garde, Fondation Robert Schuman, avril 2016

[28] Jean-Claude Juncker, discours devant le Parlement européen, Strasbourg, 5 octobre 2016

[29] Méthode de calcul dite "du pays analogue"

[30] L'article 3 du Traité comprend la politique commerciale commune, régie par l'article 207 du TFUE

[31] Commission européenne, " Conclusion des négociations sur les investissements entre l'UE et Singapour ", 17 octobre 2014

[32] Conseil de l'Union européenne, 24 février 2014, Compte rendu de la 2486e réunion des représentants permanents (Coreper)

[33] Informal meeting of the EU's Trade Ministers, Bratislava

[34] European Commission, " EU-Peru Free Trade agreement: improved market access for agricultural products ", 28 February 2013

[35] Eurostat, statistics on international goods trade, March 2016

[36] Les conclusions du G20 du 5 septembre 2016 traduisent cette inquiétude et " l'incertitude " que le vote du référendum fait planer sur l'économie mondiale

[37] International Trade Secretary Liam Fox speaking at the launch of the World Trade Report 2016. 27th September 2016

[38] "La Libre Belgique", 2 October 2016

[39] Overall this means the EU but the UK's leading three trade partners which are in order, the USA, Germany and Switzerland (Eurostat)

[40] "La France et le Royaume-Uni", a file of the French Ministry for the Economy, 2016

[41] " Classement des partenaires de l'Allemagne pour le commerce extérieur ", Federal Office for Statistics, 22 September 2016

[42] Jennifer Rankin, "Brexit trade deals: the gruelling challenge of taking back control", The Guardian, 17 August 2016 https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/aug/17/brexit-trade-deals-gruelling-challenge-taking-back-control

[43] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2011_127_R_0001_01

[44] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?uri=URISERV%3Ar17002

[45] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3Ar14104

[46] Morocco, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Algeria, Palestine, Tunisia[+ negotiations suspended with Syria and Libya]

[47] http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/caribbean/

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Institutions

Elise Bernard

—

17 December 2024

Africa and the Middle East

Joël Dine

—

10 December 2024

Member states

Elise Bernard

—

3 December 2024

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierre Andrieu

—

26 November 2024

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :