supplement

Dominique Perrut

-

Available versions :

EN

Dominique Perrut

In 2010 the collapse of Greece, in the wake of the financial crisis, caused a deep crisis in the euro zone. Leaders responded, often as a matter of urgency, with intense efforts to reform the EMU. Whilst the prudential pillar of the financial system, Banking Union, was rapidly established, economic governance has not led to the stimulation of the growth, nor has it led to the necessary convergence of national economies.

This paper aims to pinpoint the means to use to strengthen the economic pillar of EMU. Indeed this is the prior condition for the start of work to redefine its structure as a whole and in view of its completion. To this end we shall first estimate the euro zone's economic situation and recall how economic governance stands at present. The limits of the system will then be highlighted, which will lead to a definition of measures, the adoption of which seems urgent.

1 - Overview: economic governance that is unable to ensure convergence and stimulate growth

1.1 - the euro zone's economy: lack of growth, divergence amongst national economies, high unemployment

A - Zone euro

Will this be a lost decade? Whilst in 2014 the USA's economy easily rose beyond its pre-crisis level with 107 on the index in terms of the GDP, on a base of 100 in 2007, the index matching the euro zone peaked at 99 in 2014 [1], with an unemployment rate (11,6%) nearly twice that of the USA (6,2%).

Total investment by the euro zone was down by 15% in 2014 in comparison with its 2007 level (in contrast to –2% in the USA in the same time period). The euro zone investment to GDP ratio dropped from 23.9% to 19.5% in the same time period [2], whilst the public investment rate declined from 3.2% to 2.7%. However several euro zone indicators compare favourably with those of the USA: the fiscal deficit is less than half (-2.6% of the GDP in the euro zone, in comparison with –4.9% in the USA in 2014), government debt is significantly lower (94.5% against 105.2% in the same year) and the current external balance is in surplus in the euro zone (+3% in 2014), unlike the USA (-2.3%).

B - Greater national disparities.

From an economic point of view we note across the euro zone that there are strong national differences to the point that we can rank the main countries [3] in three groups:

• Around Germany, a small group of countries mainly comprising the Netherlands and Austria witnessed production in 2014 easily beyond the pre-crisis level [4]. This group is not suffering unemployment, has public accounts in line with the authorised standards and controlled public debt, along with quite significant external surpluses (7.8% of the GDP in Germany in 2014 and 10.6% in the Netherlands);

• Opposite this we find several countries in the South (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece), which experienced a sharp decline in their production (between -6% and -9% in 2014 in comparison with 2007, contraction reaching 26% in Greece), and an extremely high unemployment rate (one quarter of the working population in Spain and in Greece in 2014; 12.7% in Italy and 14% in Portugal), major budgetary deficits, notably in Spain and Greece, which inflate a very high public debt (around 130% of the GDP in Italy and Portugal, 180% in Greece in 2014). Except for Greece, the external accounts are in surplus in these countries.

• France lies in the middle: its production rose 2% beyond its pre-crisis level in 2014; unemployment (10.2%) is close to the euro zone average; the budgetary deficit is still excessive at 3.9% of the GDP and the public debt (95.6%) is slightly over that of the euro zone (94.5%). The external balance has constantly been in the negative since 2005 (-2.3% of the GDP in 2014), which reflects the country's failing ability to be competitive since that date.

These contrasts are in part a result of divergence in competitiveness between the economies, which is partly due to differences in the development of unit labour costs. This indicator shows a significant increase in costs in France, Italy and especially Greece, whilst those in Germany declined between 2000 and 2010 [5].

C - The cause of the growth deficit.

Economic stagnation in the euro zone since the start of the crisis in 2008 has been caused by three things:

• Delay in purging bank's balance-sheet of their non-performing loans by European leaders which has contributed to the reduction in lending to businesses [6]. The health-checks undertaken by the ECB in 2014 [7], as part of its new mandate as single supervisor, indeed came five years after a similar operation in the US by the Fed as of the beginning of 2009,

• The reduction in investments, which weighs heavily on the euro zone's potential growth [8],

• Shortfalls in economic governance that have led to so-called "pro-cyclical" policies, thereby accentuating recession, disparity between countries, caused amongst other things by divergence in competitiveness.

1.2 - Economic governance: present organization and ongoing reform

A - European economic governance

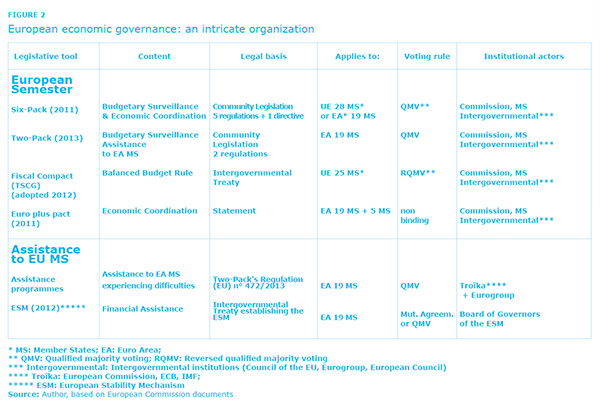

This comprises, in our opinion, the rules introduced by the European Semester, as well as assistance mechanisms to countries in difficulty, supported by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

The European Semester

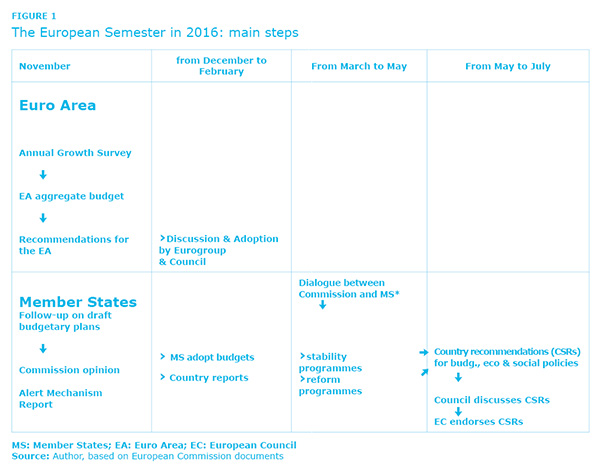

The Union and euro zone's common budgetary and economic rules have come under the European Semester since 2011. This is an annual monitoring and coordination cycle of economic and budgetary policies, extending from November to July (See Figure 1). Based on the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) of 1997 these rules were boosted by several legislative measures between 2011 and 2013.

Budgetary discipline. Budgetary monitoring applies to all 28 of the Union's Member States with stricter rules implemented in the euro zone. The excessive debt procedure (the corrective arm of the SGP), under the control of the Commission, aims to correct excesses which can give rise to sanctions if the rules are ignored by countries in the euro zone. In the event of excessive deficit euro zone Member States have to submit a "structural reform programme."

Macro-Economic Supervision is part of the new Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP), established in 2011 in which the Commission drafts an Alert Mechanism Report, based on a scoreboard of indicators. If imbalances are detected, in-depth reviews are drawn up for the countries in question. These reviews can lead, in the event of major imbalance, to country-specific recommendations. An excessive imbalance procedure together with possible sanctions, as far as the euro zone is concerned, can be launched in the worst cases.

Assistance Mechanisms.

After the introduction of several provisional aid mechanisms as of May 2010 [9] to struggling Member States within the euro zone a permanent mechanism was established. This comprised a regulatory framework [10] and the introduction of the ESM in 2012.

Regulation 472/2013 strengthens the follow-up and supervisory procedure of Member States that are subject to severe financial difficulties and provides for two types of intervention. On the one hand the Commission can place a euro zone Member State under enhanced surveillance in the event of a crisis that might spread. On the other hand, if a State requests help it must prepare a macroeconomic adjustment programme in agreement with the Commission (which works with the ECB and also in general with the IMF).

The European Stability Mechanism is an international financial institution created in 2012 by means of an intergovernmental treaty signed between the euro zone Member States [11]. The ESM's goal, whose total lending capacity is 500 billion €, is to preserve the financial stability of the euro zone using several measures: financial assistance to Member States in difficulty, intervention on the sovereign debt markets, and recapitalisation of the banks. Power is exercised by the Council of Governors, which rallies the members of the Eurogroup.

B - Reform underway

"The Five Presidents' Report", published in June 2015 [12], plans for the continued overall reform of the EMU according to three phases that are due for completion by 2025. The 1st phase which especially involves the European Semester started on 1st July 2015 and will end in June 2017. The document provides for four axes: Economic Union, Budgetary Union, Financial Union (in the extension of Banking Union of 2012) and Political Union.

Economic Union includes four measures: the creation of a system of consultative competitiveness authorities, the strengthening of the procedure involving macroeconomic imbalances, increased attention given to social results and employment, updating the European Semester.

Budgetary Union provides for the creation of a consultative European Budgetary Committee to coordinate the national budgetary councils and to provide an independent assessment of national budgets and of the euro zone's aggregated budget. Then provision has been made for the introduction of a common budgetary capacity to absorb shocks affecting the zone.

The unified external representation of the euro zone aside (notably at the IMF), Political Union (democratic accountability, legitimacy and institutional enhancement) provides three axes to consolidate economic governance: the strengthening of the Eurogroup, progress towards greater accountability and democratic legitimacy, the revision of the Union's legal framework via the integration of certain intergovernmental agreements.

Since July 2015 the Commission has been reforming the European Semester as proposed in the Five Presidents' Report. It provides [13] for measures notably focusing on the reorganisation of the calendar into two phases, the rationalisation of economic governance, the creation of national Competitiveness Councils and of a European Budgetary Committee, increased focus on employment and social data and finally more targeted support to structural reforms. Finally in view of the transition over to phase 2 of the process that aims to complete the economic and institutional structure of EMU, the Commission is to present a White Paper in the spring of 2017.

The single currency creates greater interdependence between economies since each country can no longer wield the arm of the exchange rate. The introduction of the euro therefore heightens the need for a convergence of the economies and more restrictive discipline. However, after the launch of the euro we witnessed diverging development in the economies, which has threatened the zone with collapse. Guaranteeing the rapprochement of the economies and raising growth prospects within an overall strategy for the euro zone is an issue of capital importance. This has to be achieved with the support of recent reforms and also by correcting the weak points in governance which we shall now look into.

2 - The weaknesses in economic governance

In spite of the contributions made by the new framework that has been introduced economic governance in the European Union and the euro zone has brought some major limitations to light: disparate institutional organization, complex procedures, sometimes ill-adapted tools and finally lacking decision making capacities and implementation. The reforms now underway finally do not provide sufficient answer to the economic difficulties in hand.

2.1 - Disparate institutional structures

Based on the Stability and Growth Pact, the institutional structures that reformed governance between 2011 and 2013 now look like various statute texts that have been piled on top of one another.

The legal nature of these texts is heterogeneous. The community texts (7 regulations and one directive) run alongside two intergovernmental treaties (the "Fiscal Compact" TSCG [14], and the ESM), whilst the "Euro Plu Pacts" is a non-binding declaration.

Four different sets of Member States are involved depending on the measures in question: the 28 EU Member States are affected by the Six-Pack, the 19 members of the euro zone by another part of the Six-Pack, the Two-Pack and the ESM; 25 States by the TSCG; 24 States by the Euro Plus Pact (euro zone and 5 non-Members) [15];

Voting modalities vary according to the legal framework: the qualified majority vote (sometimes the simple majority) by the EU States or those in the euro zone (the State concerned by the vote is excluded), regarding measures in the Two-Pack and the Six-Pack; it entails the reversed qualified majority vote of the euro zone members within the framework of the TSCG [16]; as far as the ESM is concerned the decisions of the Council of Governors are taken - depending on the subject - either by a joint agreement or by an 80% qualified majority (or in certain cases by 85%), sometimes still by the simple majority but in fact Germany can use its right to veto [17].

The Union's institutions' intervention in the procedures also varies depending on the area in question:

- Regarding the European Semester, in addition to the exchanges between the Commission and the States, the European Council and the Ecofin Council can also intervene, in addition to the Eurogroup if the euro zone is concerned.

- Regarding assistance measures another set of institutions comes into play comprising the Commission, the ECB, the IMF and the Eurogroup.

2.2 - The complexity of the procedures.

During the European Semester 2016, three procedures together with many documents have gone hand in hand [18]. (See figure 2)

- the assessment of the euro zone's aggregated budget (November 2015) on the basis of the macroeconomic plan provided by the Annual Growth Survey. This process leads to recommendations of the Commission as discussed by the Eurogroup and adopted by the Council in January 2016;

- the monitoring of the national budgets gives rise to an opinion on the part of the Commission on the projects, then to an adoption by the members of the euro zone (December 2015) before the drafting of their Stability Programme [19].

- The macroeconomic imbalance procedure which starts with the Alert Mechanism Report (November 2015) and is extended by the country-specific reports (February 2016) then in national reform programmes issued by the States [20].

- After exchanges between the Commission and the States (between March and May 2016) the two procedures, budgetary and macroeconomic, converge in the Commission's recommendations in terms of fiscal, economic and social policy assessed by the Council (June 2016), then adopted by the European Council (July 2016).

Based on secondary legislation, which tripled in volume between 2008 and 2014 [21], the calendar is an imbroglio and so obscure from a procedural and technical point of view that according to some well qualified observers only a few experts and technocrats can understand the whole. As for political leaders and national parliamentary representatives they have "at best an 'approximate' idea of what the system involves."

2.3 - Sometimes ill-adapted tools and standards

The instruments that have been introduced by successive legislation are sometimes wanting due to their rigidity, as far as the budgetary rules are concerned, and sometimes due to their inadequacy, as far as the supervision of the euro zone or the recent procedure for macroeconomic imbalance are concerned.

A Pact that is negative for growth? The aim of structural balance, which is the focus of the Stability and Growth Pact, was not modified in the reform undertaken between 2011-2013. It was quite the contrary, and this standard was established as a "golden rule" in the TSCG. But from the standpoint of growth and innovation, public investments, which are generators of future wealth, and which can be financed through debt in virtue of this, should not be taken into account in the structural balance. Likewise since debt is eroded by inflation this ought to be integrated into the calculations [22].

Pro-cyclical standards? Economic cycles sometimes require fiscal impulse and sometimes deceleration. But are these fluctuations being sufficiently taken into account in the present context? The questions deserves to be asked, since as of 2010 austerity policies were introduced, after the deep recession of 2009 (-4.5% in the euro zone), which were followed by further recession in 2012 and 2013.

In response to the pro-cyclical risk, the budgetary reforms of 2005 and then 2011-2013 definitely brought about modifications to the adjustment trajectories to be followed by the Member States. But on the other hand, the path back to balance has become more restrictive. Is the fiscal consolidation demanded by the new framework too fast? Judging by empirical observations, the budgetary policies undertaken in the euro zone since 2000 have been either pro-cyclical, or neutral, with a notable exception in 2009. The pro-cyclical link between budgetary austerity and recessions seems particularly clear in 2012 and 2013 [23].

However the link between budgetary policy and regulatory measures cannot be established in a strict manner since other considerations have to be taken into account, thereby often leading to pro-cyclical action on the part of political leaders, to prevent for example any excesses which would expose them to reactions on the markets.

The euro zone's strategy is not armed with the appropriate instruments. The European Semester's calendar was reorganised in 2016 [24]. A first phase was devoted to recommendations for the euro zone (adopted in January). The Member States must now integrate these recommendations during the second phase which runs from February to June/July.In 2014 and 2015 recommendations for the euro zone advocated an aggregated budgetary policy in line with growth and the economic cycle. But some of these guidelines cannot in reality be applied by the States. Indeed in 2015 the countries placed under the corrective chapters of the SGP (for excessive deficit) and therefore deprived of any room to manœuvre, represented 38% of the euro zone's GDP. As for those under the preventive arm, which counted for more than half of the GDP, their margins remained limited. It is rightly argued therefore that the "specific recommendation for the euro zone regarding the aggregate fiscal stance is not operational." [25]

The limits of the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP). The dangers of economic divergence between the States that might lead to balance of payments crises were hardly taken into account by the Pact of 1997. The so-called broad guidelines for the economics policies, created in 1997 was ineffective and non-binding [26]. But divergences in costs between States during the entire decade 2000 to 2010 have led to serious differences in competitiveness and external current account balances. The introduction of the MIP in 2011 aims to remedy this shortfall. The Commission's recommendations in virtue of this notably aimed to rebalance the States' current accounts. However contrary to advice regarding the budgetary chapter, this objective does not lend itself to the definition of clear national policies based on specifically identified tools.

2.4 - Low level of recommendation implementation.

The Commission clearly notes the lack of application of its recommendations by the countries. "The European Semester certainly strengthened the coordination of economic policies at EU level but the lacking and sometimes inexistent implementation of the main country-specific recommendations has brought its efficacy into question [27]." A study notes low implementation levels of the Commission's recommendations and even of a decline in the latter since the reforms of 2011-2013. It is said to have fallen from 40% in 2011 to 29% in 2014 [28]. The concrete examples of France and Germany, in the country-specific reports published in February 2016 show in the first instance an implementation of recommendations in 2015 below the average and an extremely low level in the latter case.

These problems have been caused in part by the formulation of the recommendations. Too many in number initially for each of the Member States [29], they were recently simplified by the Commission. More targeted and fewer in number, they now focus on macroeconomic and social goals over a 12 month period [30]. The difficulty for governments to justify reform politically might also explain the problems in appropriating these European recommendations at national level. However the main cause of this flagrant lack of application must lie in the low decision making capacity of the intergovernmental bodies, with Eurogroup being the first of these.

2.5 - A lack of decision making capacity.

The reforms of 2011-2013 set in place a system of stricter rules together with almost automatic voting of sanctions for the members of the euro zone. However no sanction has been delivered to date against a Member State, whether in terms of the budget or under the MIP. In spite of major macroeconomic imbalances noted by the Commission in five countries in 2015 and also in 2016, the latter did not propose the activation of the procedure for excessive imbalance, which the ECB regrets [31].

The intergovernmental bodies (Council and Eurogroup) mostly avoid the use of the formal vote and take their decisions as part of the "open coordination method", in other words "the peer pressure" method. This approach is not really effective for several reasons: on the one hand there is little effect on the major countries; on the other, each of the members has no real desire to criticise another member State since it hopes for the same clemency in return; finally follow-up to the implementation of recommendations is not within reach of the small countries of the euro zone; in fact only Germany does this [32].

Eurogroup is still an informal body, without any operational resources. Like the other Union institutions, except for the ECB, the Eurogroup has been weakened by the crisis and side-lined to the benefit of the Euro Summit at certain crucial times. The increase in "Last Resort Summits" for Greece in 2015 again damaged its image. Some believe that the "Eurogroup is not a place in which one can rise above national interests but one where these clash" [33]. Moreover the rise in number of institutions, on the occasion of the assistance plans (intervention by the Troika and the ESM) and sometimes their overlapping, is leading to a dilution in accountability, of which the Troika is the most striking example.

2.6 - Inadequacy of the reforms put forward.

An assessment of the shortcomings in present economic governance led to positive points in the Five Presidents' Report: the aim to simplify the European Semester, its re-organisation into two phases, the aim to achieve one representative for the euro in the international arena.

However as far as the major questions facing governance are concerned the report has its limitations: it does not provide an answer to the central issue of the weak decision making capacity of the intergovernmental structures. The proposals made for the strengthening of the Eurogroup are as measured as they are vague. The budget and competitiveness Councils are of interest but their consultative nature reduces their scope and these new bodies will only make a system that is unanimously criticised because of this more complex. Finally the preparation of the second phase in the process remains unclear.

3 - A pilot to steer governance to guarantee coherence of the instruments used

Many proposals to reform the EMU's economic governance do not plan for any changes to the Treaties in the near future. These are deemed unrealistic given the present climate of Euroscepticism and the electoral calendar of 2017. There are some priority proposals which can be undertaken without changing the Treaties to make economic governance more effective.

3.1 - Ending inaction: a Finance Minister for the euro zone

The governance of the euro zone is typified by the co-existence of the Commission, which has significant resources, alongside the Eurogroup, which has none. Merging the presidency of the Eurogroup with the Vice-Presidency of the Commission responsible for the euro [34] would help strengthen the Eurogroup by providing it with resources according to the model applied to Foreign Affairs [35].

In this way the Eurogroup would have some of the resources enjoyed by the DG ECOFIN, playing the role of the euro zone's Secretariat General. This logistical support would provide the Member States with the multilateral supervisory capacities which they are sorely lacking. This reorganisation would probably mean that the examination of the country-specific supervisory files would be given to other bodies so that the President does not have to play both the role of judge and Advocate General. The President of the Eurogroup would help to implement the recommendations made to the euro zone as a whole which has still not been achieved [36]. He would be accountable to the European Parliament. The European and national parliaments would be part of this in ways that still have to be defined [37].

As a part of this the President of the Eurogroup would be the perfect candidate to represent the unified euro zone internationally, at the IMF and within the major international organisations [38]. This measure is provided for in the Treaties [39]. Following the centralisation of banking supervision within the ECB in 2013, this unique representative would enable the euro zone to play its full role in stabilising the international monetary system and to regulate the financial industry.

Similar reform might be provided at the top of the EU, by the merger of the Presidency of the European Council with that of the Commission [40].

In the long run these strengthened government bodies might evolve towards a similar organisation to that of the ECB, whose decision making capacity is challenged by no one. The ECB's governance comprises a small Executive Board and a Council of Governors [41]. The Eurogroup might be reorganised along the same lines with a board comprising the President and five full time members, appointed by the European Council after consultation with the Eurogroup. The Board would be responsible for following up on the Eurogroup's decisions, both at euro zone level and with each country and for preparing its work. In addition to the euro zone Finance Ministers, the Eurogroup would include the members of the board. Each member of this extended Eurogroup would be able to vote.

3.2 - Reforming the tools of the European Semester

A - Clarifying Procedures.

The European Semester would benefit from the clarification and alignment of its procedures.

The three monitoring procedures (budgetary supervision, Macro-economic imbalance procedure (MIP) and Europe 2020) should be clarified in terms of their respective goals, limits and their duration. Indeed the budgetary procedure and the MIP overlap, since they both address government debt. Likewise the MIP overlaps with the Europe 2020 strategy, whose goals are more long term.

Moreover there are contradictions between the Union's present priorities in support of investment and the mechanical effect of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) which tends to slow public investment, due to its inclusion in the calculation of the structural balance.

Taking simplification further under the existing framework started by the Commission and without changing the legal framework [42], procedures could be combined, notably during the important phases, in a single document (the budgetary aspects might feature, in the country-specific reports, alongside the MIP and Europe 2020 indicators for example).

The merger of the preventive and corrective arms of the SGP might be undertaken, with a set of common indicators and rules, together with two types of condition in view of the effective implementation of the recommendations [43].

B- Revising tools and standards

In response to the limitations noted earlier governance tools might be revised according to three lines of approach.

- Integrating national strategies with those of the euro zone. It does not appear realistic to count on the States' implementation of the recommendations made to the euro zone in a context in which the former find themselves in the majority under the constraint of the SGP. Room to manœuvre should therefore be created regarding the SGP so that countries can modulate their adjustment trajectory to converge with overall goals [44].

The recommendations made to the euro zone should gain in clarity and sometimes relevance in terms of their alignment with those addressed to the countries and in the identification of priorities [45].

- A MIP focused on convergence. The Commission acknowledges that the "asymmetrical" nature of adjusting external imbalances which was significant amongst countries in deficit but low or zero for the countries in surplus, has affected growth [46]. This has led to the ineffective nature of the MIP, the reason for which lies in the multiple monitoring indicators and the weak link between the recommendations and real tools which leaders have at their disposal.

The MIP should be refocused on its main goal: the correction of external imbalances to guarantee the convergence of the economies. This should be undertaken by the definition of a central indicator: the current external balance. As in the budgetary procedure, adjustment trajectories would be set towards a chosen target [47]. Finally doubt might arise as to the interest of the competitiveness councils, the establishment of which is being considered [48]. Their networking might be useful from the point of view of reducing divergence between countries in terms of cost and competitiveness, but their intervention might further complicate the European Semester [49].

- To revise and make budgetary tools more flexible at the service of growth. Flexibility margins should be created for the Member States in view of taking on board the goals assigned to the euro zone, to foster investment, which is a Union priority, whilst the rules do not encourage and are even discouraging countries in deficit. It seems opportune to see whether the reforms of 2005 and 2011-2013 have taken the economic cycle sufficiently into account.

Thought about the revision of the tools should be launched now in view of modifying the Treaties following the completion of the EMU [50]. Hence the calculation of the structural balance should be revised to take on board these considerations. Likewise since economic conditions have changed the deficit standard of 3% and the public debt of 60% of the GDP are no longer coherent. Finally four monitoring indicators might be reduced to two comprising a single budgetary anchor (the government debt/GDP ratio) and one operational instrument (a government spending development rule, with an automatic corrective mechanism [51]).

***

In the wake of the sovereign crises at the beginning of the decade, the risks caused by unsustainable divergence between its members continue to weigh heavy on the euro zone. Aware of these threats, leaders have undertaken a global reform of the EMU. Within this project, apart from Banking Union that successfully started in 2012, the reform of the economic governance of 2011-2013 addressed some sensitive issues: the rescue of member countries, correction of macroeconomic imbalances, fiscal consolidation.

This measure that was redefined as a matter of urgency, now seems disparate and complex. At the heart of these inadequacies there is weak decision making capacity in a system whose burgeoning organisation is compromising efficacy and watering down accountability.

A decisive measure to strengthen the Eurogroup by the introduction of a European Finance Minister seems to be a vital condition to correct the shortcomings of governance, to foster economic convergence and to raise growth objectives. This prior stage to any type of movement towards the completion of EMU must be prepared and launched immediately.

[1] : This is the GDP index in real terms at 2010 prices. Statistical Annex of European Economy, European Commission, ECFIN, Autumn 2015.

[2] : For a level deemed desirable of 21% to 22%.

[3] : These represented 90% of the euro zone's GDP in 2014.

[4] : Except the Netherlands, whose production stagnated over the same period.

[5] : See on this point: Aglietta M., Europe : sortir de la crise et inventer l'avenir, Michalon, 2014

[6] : At the end of 2015, loans to businesses in the euro zone at market prices were 2.6% below the 2007 level. Source ECB.

[7] : See Perrut D., "The ECB's health-checks of the banks: a necessary but insufficient stage in the reform of the euro" European Issue n° 332, Robert Schuman Foundation November 2014; and ECB, Aggregate report on the Comprehensive Assessment, October 2014.

[8] : Potential growth can be defined as a level of production that an economy can reach without a rise of inflation given its demography, its capital stock and its productiveness.

[9] : This notably involves the European Financial Stability Mechanism (EFSM ) and the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), created in May 2010.

[10] : Regulation 472/2013, par t of the Two-Pack, based on the TFEU Art. 121-6 (multilateral monitoring) and 136 (fiscal and economic coordination).

[11] : Treaty establishing the European Stability Mechanism, signed on 2nd February 2012.

[12] : "Completing European Economic Monetary Union" a report prepared by Jean-Claude Juncker together with Donald Tusk, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Mario Draghi and Martin Schulz, 22 June 2015. These people are respectively presidents of the European Commission, the European Council, the Eurogroup, the European Central Bank and the European Parliament

[13] : "Commission Communication on the measures to take to complete EMU", 21 October 2015, COM(2015) 600 final

[14] : Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Convergence within the Economic and Monetary Union adopted on 2nd March 2012 by 25 Member States.

[15] : See Alcidi C., Giovannini A., Piedrafita S., "Enhancing the Legitimacy of EMU Governance", Study for the Econ Committee, December 2014.

[16] : Art. 7 of the TSCG; the reversed qualified majority means that a measure is adopted except if a qualified majority votes against it.

[17] : The ESM decisions involving rescue plans are subject to Germany's veto since these must be approved by the Bundestag and confirmed by the Constitutional Court of Karlsruhe.

[18] : Commission Communication on the measures to take to complete EMU COM (2015) 600 final, 21.10.2015.

[19] : Or convergence programme for EU countries that are not par t of the euro zone.

[20] :Inclusion of Europe 2020 Strategy's indicators in this procedure introduce additional complexity

[21] : Pisani-Ferry J., Rebalancing the governance of the euro area, n° 2015-02/May, France Stratégie

[22] : See M. Aglietta; et Sterdyniak H., "Ramener à zéro le déficit public doit-il être l'objectif central de la politique économique ?", OFCE papers, n° 17, April 2012.

[23] : Pisani-Ferry J.; Bénassy-Quéré A., "Economic policy coordination in the Euro Area under the European semester", November 2015, European Parliament; E.C. Report on the Euro Area, 26/11/2015 SWD (2015) 700 final.

[24] : This re-organisation follows the advice of the Five Presidents' Report

[25] : Bénassy-Quéré A. ; also see Darvas, Z. and À. Leandro, Economic policy coordination in the Euro Area under the European Semester, November 2015. These authors stress the lack of coherence between the recommendations made to the euro zone and those notably made to the Mayn countries.

[26] : Regulation (CE) n° 1466/97, Art. 5., together with the SGP.

[27] : Annual Growth Survey of 2015, COM (2014) 902 final ; see also the Commission's Communication on the measures to undertaken to complete EMU 21st October 2015, COM(2015) 600 final,.

[28] : Darvas Z. and A Leandro,

[29] : Zuleeg F, Economic policy coordination in the Euro Area under the European Semester, November 2015

[30] : Commission Communication of 21st October 2015.

[31] : ECB, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2/2016

[32] : Gros D. and Alcidi C., "Economic policy coordination in the Euro Area under the European semester", December 2015

[33] : Moscovici P., "Après le psychodrame grec, quelles améliorations pour l'UEM ?", Notre Europe, 30 September 2015.

[34] : Here we mean the Vice-President of the Commission responsible for the euro and social dialogue. The latter also supervises the DG ECOFIN (economic and financial affairs). This proposal was put forward by J-C Trichet, the then ECB president during the award of the Charlemagne Prize in Aachen on 2nd June 2011. See also Chopin T., Jamet J.-F. and Priollaud F.-X., "Political Union for Europe", European Issue, Robert Schuman Foundation, n°252, September 2012 and "Réformer le processus décisionnel européen : légitimité, efficacité, lisibilité", Revue politique et parlementaire, July2013; Henderlein H. et Haas J., "Quel serait le rôle d'un ministre européen des finances ?", Policy paper, Institut Jacques Delors, October 2015 and Pisani-Ferry J., op. cit. It should feature in a report now being written by E. Brok (DE, EPP).

[35] : The Foreign Affairs Council is chaired by the Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. It is supported by the resources of the European External Action Service (EEAS).

[36] : Gros D. and Alcidi C., 2015,.

[37] : On this point see Chopin T. "Euro zone, legitimacy and democracy: how should we respond to the issue of European democracy?" European Issue, Robert Schuman Foundation, n°387, April 2016. Moreover article 13 of the TSCG provides for the modalities of association of the European and national parliaments on economic issues.

[38] : This measure is advocated in the Five Presidents' Report. It was also the focus of a Commission communication: COM (2015) 602 final and a proposed Council decision : COM (2015) 603 final, 21st October 2015

[39] : Article 138 of the TFEU.

[40] : This might be done on the basis of an interinstitutional agreement provided for in the Lisbon Treaty (Art. 295 du TFUE).

[41] : The governance of the ECB comprises two chief bodies in the Mayn, the Council of Governors and the Board. Comprising six members including the President and the Vice-President, apart from the everyday management of the ECB, the Board implements the monetary policy defined by the Council of Governors, prepares the latter's meetings from which it can receive delegated power. The Council of Governors comprises the Board and the Governors of the national central banks of the euro zone, with each member enjoying a vote. The Council of Governors defines the Union's monetary policy (Protocol 4, annexed to the EU Treaties, on the statutes of the ESCB and the ECB, art. 10 to 12)

[42] : Commission Communication du 21/10/2015,

[43] : Cf. Andrle M. & Al., "Reforming Fiscal Governance in the European Union", IMF Staff Discussion Note, May 2015, SDN/15/09.

[44] : According to a similar procedure to that used by the Commission at the beginning of 2015 in support of the EU's priorities.

[45] : For example in 2015 there is no mention of the problem of external surpluses in the recommendations to the euro zone or to Germany.

[46] : Commission staff working document, Report on the euro area, SWD (2015) 692 final, 26.11.2015

[47] : This idea is the same as the one expressed by Bénassy-Quéré A., 2015

[48] : Recommendation for a Council recommendation on the establishment of National Competitiveness Boards within the Euro area. COM(2015) 601 final, 21.10.2015.

[49] : Gros D. and Alcidi C.

[50] : This modification would occur in phase 2 provided for in the Five Presidents' Report.

[51] : IMF

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

Ukraine Russia

Alain Fabre

—

11 March 2025

Gender equality

Juliette Bachschmidt

—

4 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :