Enlargement and Borders

Gilles Lepesant

-

Available versions :

EN

Gilles Lepesant

Research Director at the CNRS (CEFRES, Prague)

In 1989 as in 1918 Central Europe witnessed the dawn of an era that was favourable to a re-configuration of the political map on the ruins of defeated empires. In 1918 the process was cut short because of the instrumentalisation of the minorities living in the new states, the social, economic and political consequences of the 1929 crisis and Germany's refusal to accept the post-war territorial settlements.

A striking fact in comparison with 1918 is that post-1989 re-structuring took place in a European context. The convergence of a claim for Europe and the economic and political model of the European Union led, except for Yugoslavia, to a peaceful transition. Hence Central Europe had an opportunity in 1989 to divest themselves of an in-between geostrategic position, to conciliate political fragmentation requested by the nations and a grand market which was vital for economic development.

In the end the European Union has changed in structure. Following the enlargements of 2004, 2007 and 2013 the number of Member States has almost doubled (rising from 15 to 28) via a policy based on criteria (defined during the European Council of Copenhagen in 2004), a great amount of aid, asymmetrical liberalisation of trade and gradual adoption of the community acquis.

1. The EU's new economic geography

"The very notion of solidarity in Europe, between East and West, between rich and poor, between old and new Member States has been set. The successes of the last thirty years, from the internal market to the euro not forgetting enlargement, will be put to the test as never before"[2]. Made at the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008 by D.Miliband, the then British Foreign Minister, this diagnosis has proven true in the years that have followed.

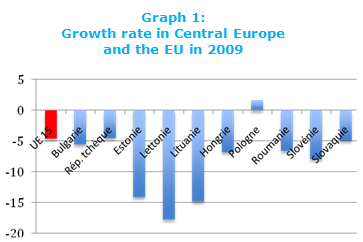

Central Europe was the focus of debate during the crisis because of the financial difficulties encountered by some Baltic States and Hungary. "Central Europe is the sick man of the emerging markets," wrote economist Nouriel Roubini[3]. What can we say in 2014? The crisis brought the convergence process temporarily to an end. In 2009 all of the new Member States (except for Poland) experienced growth lower than that of the EU due to a massive reflux of foreign capital and the dependency of the economies in question on exports.

Source : Eurostat

Source : Eurostat

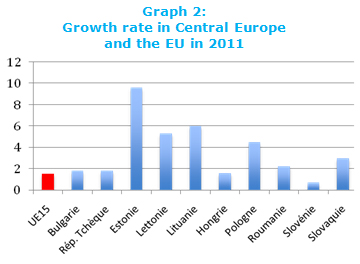

However in 2010 several of them were in a better economic situation and in 2011 only one State recorded growth below that of the EU.

Source : Eurostat

Source : Eurostat

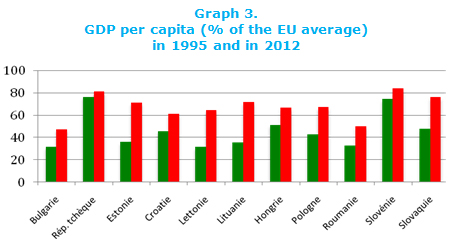

Over the period 1990-2012 convergence occurred even though Central Europe has been more diverse than ever before. The membership process helped Central Europe gain in terms of stability and to import a legislative framework that is familiar to most foreign investors who have also been attracted by modest labour costs. Although in the 90's Central Europe was still quite unattractive the stock of FDI's tripled between 1998 and 2004 and the trend continued until the crisis in 2009. Per inhabitant the flow towards Central Europe rose beyond that directed towards other emerging countries like Brazil, Mexico and China[4].

Source : Eurostat

Source : Eurostat

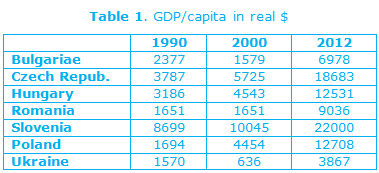

In comparison with the eastern neighbours the choice of Europe which came after the collapse of communism has paid off, as seen by the progress achieved by the countries of Central Europe and Ukraine respectively.

Source : Banque mondiale

Source : Banque mondiale

In 1990, the GDP/capita in Poland and Ukraine were similar. Two decades later the ratio was 1:4 between the two countries. In comparison with the countries in the south of Europe some States, which joined in 2004, caught up with and rose beyond Greece and Portugal in 2012. In sum a new European economic layout has emerged, the establishment of which has been accelerated by the crisis.

One clear concern regarding the countries of the Central Europe on the eve of their accession involved their ability to integrate and implement the community acquis. According to scoreboard drawn up by the European Commission[5], half of the most virtuous countries in this regard in 2012 were the countries of the Central Europe whilst only one (Poland) featured amongst the 10 countries having committed the most infringements.

The process to integrate the European Union has given rise to a clear re-direction in trade with the EU and notably Germany becoming the main trade partner in the wake of the collapse of the communist bloc. Since 2010 there has been a dual development. Russia has stepped up its presence in the region with an increase in investments and trade - it is still true that this is largely dominated by the delivery of hydrocarbons. Exports by Central European countries towards Russia multiplied by five between 2004 and 2011 (6.6 billion $ to 30.5 billion whilst imports rose from 21 to 66 billion)[6]. In all Russia's share in Central Europe's exports have remained at a level close to that of 1993 (5% in comparison with 6% after 2.5% in 2004). The situation varies however from one country to another, Russia's share being significant in the Baltic States (16%) whilst in Romania it is not over 2%. The region's share in trade with Russia has also stabilised. It totalled 12% of Russia's exports and 9% of its imports in 2012[7]. However the place of hydrocarbons is so important that only two countries have been able to make trade surpluses with Russia over the past few years (Estonia and Latvia).

Moreover some countries in Asia, like South Korea and Japan have stepped up their presence since the 1990's. China, which made a late entry, is now gradually becoming an important partner. Of course Chinese investments abroad did not rise beyond 1 billion $ per year between 2004 and 2008 but in 2009 and 2010 they totalled 3 billion and in 2011 they rose to 10 billion. This development is part of the Chinese strategy to internationalise - "Zou Chu Qu"[8] - which targets access to technologies, brands, natural resources and helps to diversify foreign exchange reserves.[9]. China's goal was expressed by its Prime Minister during a trip to Poland in 2012: double trade with Central and Eastern Europe by 2015. In 2012 China was Poland's third import country (for a total twice that of imported goods from France).

The final part of integration, joining the euro zone, is included in the Membership Treaties which all of the new States signed. Since 2004 four countries of Central Europe have joined (Slovenia, Slovakia, Estonia and Latvia) and none of the States which joined in 2004 and 2007 were in deficit or debt in 2013 equal to that of France (except for Croatia in terms of the deficit). Given the populations' expectations and investment requirements this performance is not without significance and explains why the euro zone has continued to expand. Some new Member States have made an unprecedented effort. Hence the crisis severely damaged the public finances of the Baltic States, which opted for austerity, with major financial aid on the part of the EU and the IMF. Latvia recovered its pre-crisis GDP level in 2012. Seven years after experiencing a deficit of 22% it entered the euro zone on 1st January 2014. In several countries in the region the opportunity to join the euro is the subject of debate however, with the desire to be an integral part of the European project opposing eurosceptic arguments or fears about the state of economic readiness. In Poland, Marek Belka, Director of the Central Bank warned against any premature accession to the euro zone[10], since the country still has to to move beyond a price-competitiveness based development model. Conversely supporters of a rapid integration into the monetary union speak of the pressure this would have in support of taking economies upmarket. The latter is precisely the challenge that Central Europe will face over the next few years.

2. 10 years after accession, which development model?

Although the crisis has not challenged the convergence of Central Europe it has revived questions about its development model. The latter is based on quality labour from a technical point of view, on a young population, on fiscal attractiveness, on modest wages, on flexible social legislation, on protected monetary sovereignty (in some cases) and on geographic proximity. But some of these assets, notably that of demography will gradually disappear.

To date Central Europe has the youngest population in Europe but it is the focus of the most pessimistic forecasts for the period 2008-2060. Over this period several countries will experience a sharp decline in their population, notably Bulgaria (-18%), Latvia (-26%), Lithuania (-24%), Romania (-21%) and Poland (-18%)[11]. The latter will probably have 31 million inhabitants by 2060 in comparison with 38 million in 2008. A corollary of this development is that the rate of dependency in the new Member States will increase significantly. This development is mainly the result of a fall in the birth rate since the end of the 1980's, to which we might add often permanent migration.

Between 1998 and 2013 Estonia lost 7% of its population. Between 2001 and 2012 the population of Latvia decreased by 7.6%, that of Lithuania by 10.1% (a similar scenario in Spain would be the equivalent to the loss of 11 million inhabitants)[12]. Adapting retirement systems, opening up to immigration creating conditions for rising birth rates: Central Europe will face all of these unprecedented challenges over the next few years.

Another challenge comes in the shape of organising a development model that is not competiveness-price based. The cost of labour should remain lower than that in Western Europe long term. It varies between 30 and 35€ in Western Europe and between 5 and 7 in Poland and Hungary. With productivity rising slowly the unit cost of labour increased sharply in reality until the crisis. In order not to be restricted to a status of medium income countries the states in Central Europe must increase productivity and invest in innovation. However from this point of view the public and private spending on R&D ratio to GDP is the weakest in the EU and very few patents are registered (8 to 1 million inhabitants in 2010 in Poland, 109 in the EU). However foreign investments in the manufacturing industry (gradually being overtaken by the development of the tertiary sector), even if they are not accompanied by the establishment of R&D centres, contribute significantly to the acquisition of new know-how. The fact that the region has become the support base for the European car industry (like the Iberian peninsula in the 1980's) has enhanced its competences in this sector - with the risk of creating a dangerous dependency at a time when the European market seems to be saturated.

What role can the cohesion policy play in this necessary move upmarket? For the period 2014-2020, 40% of European funds (to a total of 351 billion €) will be used in Central Europe. Designed originally to help the implementation of the internal market, regional policy increasingly seems to be a necessary factor for the success of Monetary Union. The latter prevents those countries suffering a competitiveness deficit from recurrently using devaluation. Moreover since the integration of the markets has occurred ahead of the integration of policies the euro has no adjustment mechanisms that characterise a federal state. In this context the funds allocated as part of the cohesion policy change the structure of economies on condition that they do not just become an equipment policy.

From this point of view the fact that the "old" EU countries worst hit by the crisis were the main beneficiaries of the cohesion policy since they joined confirms the need to couple the receipt of European funds with policies that foster innovation and education. Without being able to prevent a real estate bubble Ireland had started measures to stimulate innovation and found endogenous development based on major foreign investments. Central Europe faces the same challenge today.

3. The political and social challenges of enlargement

In Central Europe the sharp rise of populist movements is not surprising due to the effort demanded of the population since the beginnings of transition and the political cleavages inherited from the communist period. In Poland the eurosceptic party PiS (Law and Justice) came to power in 2005 arguing that the renewal of the elites was incomplete and by playing the difficulties experienced by the social groups and regions which were hardest hit in the transition. Populism also succeeded in Slovakia and especially in Hungary, to a backdrop of a feeling of historical injustice and economic crisis. On January 1st 2012 a new "Fundamental Law" and several controversial organic laws entered into force there. In this instance the Commission no longer has the means available to it during the membership negotiations. It can use a wide range of its competences to launch infringement procedures (three of these were launched against Hungary)[13] or turn to Article 7 which provides for the suspension of a defaulting State's voting rights. Given the difficulty in using this last measure the Commission adopted a warning measure in March 2014 that can be triggered if a country is suspected of not respecting the rule of law. Moreover a "cooperation and verification mechanism" was introduced during the accessions in 2007 regarding Romania and Bulgaria in order to assess their progress in the judicial area and in the fight to counter organised crime and corruption. Regarding the latter 8 of the 15 most virtuous states in the world are European countries but none of these are in Central Europe[14].

In the West enlargement has often been perceived via the lens of either relocations or immigration. Regarding relocations nothing shows that the latter have been the cause of a significant number of job destructions. According to a study by INSEE in 2007[15], relocations (displacement of an activity existing previously in France) destroyed between 20,000 and 43,000 jobs per year between 2000 and 2003. However few relocations involved Central Europe and the jobs destroyed were barely significant in comparison with the number of jobs created. Above all these relocations should be added to the new opportunities that the economies of Europe found in Central Europe in terms of investment and exports. Hence Central Europe was one of the rare regions with which France has had a foreign trade surplus since the transition began and it features amongst the leading foreign investors.

Regarding immigration the Membership Treaties of 2004 and 2007 planned for transitional period summarised by the formula 2+3+2. In the first two years following enlargement, the "old" Member States were allowed to restrict access to their labour market. This measure could be extended for another three years after notifying the European Commission. In the following two years restrictions were only possible if there was a significant danger of destabilising the labour market. Three states, Ireland, the UK and Sweden, did not ask for any transitional period and only Germany and Austria used the maximum transitional period of 7 years. In the end the UK experienced one of the biggest migratory waves in its history (more than 560,000 new arrivals on the job market between May 2004 and May 2006). Since then arrivals have continued but at a lesser rate to reach a total of around 1.5 million people[16]. Various studies have concluded that these arrivals have had a low impact on depressing salaries (and then only on the lowest salaries) and a positive impact on the country's economy.

One striking fact is that the crisis caused the return of some migrants but did not prevent further arrivals, notably to the benefit of the agricultural sector. The opening of the labour markets of other Member States did however contribute to re-orienting flows, notably towards Germany which also attracted populations from the south of Europe after the 2008 crisis. In 2012 Germany had taken in more immigrants than during the previous 17 years (1.08 million people). Although the flow mainly involved the countries of Central Europe, notably Poland (176 000), Romania (116 000), Bulgaria (59 000), but the highest increases in migrants comprised the Spanish, Greeks and Italians. In the case of Romania and Bulgaria nine Member States asked for the longest transitional period (up to the end of 2013), including the UK. After having underestimated immigrant arrivals in 2004 the latter was concerned about a further massive wave.

Given the difficulty in questioning the freedom of movement, one of the four freedoms that found the European project, debate focused on the issue of posted workers[17]. Abuses were indeed mediatised in the UK, likewise in Germany and France since the latter two countries hosted the greatest number of posted workers in Europe. In March 2014 an agreement was found between the Greek Presidency of the Council and European Parliament in order to manage practices in this area and to amend a directive dating back to 1996[18], itself designed to regulate the flow of workers following the accession of Spain and Portugal at the time.

Although the supposedly damaging effects of the opening of the labour market and relocations are not supported by any study they have helped to empty the enlargements -which received little support on the part of the "old" Member States - of their meaning. One of the main shortfalls in the enlargement strategy seems that it was not explained to the full. As a result political actors who support national introversion have been able to point to the risks of migration and the effects relocations would have on employment. The crisis has naturally amplified the fears of public opinion. Although at the end of 2008 36% of European citizens were against any further enlargements, this percentage rose to 53% in 2013, whilst 37% of citizens said they were in favour of further accessions[19]. In 2013 the countries in Western Europe were most against any further enlargements (60%) whilst those which had entered most recently approved further enlargements (71% in Poland). Those most against it were the contributing States (Germany, France, Finland) and the least desired countries were Turkey, Kosovo and Albania, whilst the countries which enjoyed the most support (Switzerland, Iceland, Norway) were the countries which least wanted to join in the short term.

4. The end of the enlargement policy?

Accession by Croatia on 1st July 2013 leads us to believe that the enlargement policy is continuing, especially since membership negotiations with Serbia started in January 2014. In fact progress is slow and enlargement is no longer a major part of the European policy since the EU is insisting more than ever before on the respect of the rule of law and on the administrative capabilities of the candidate countries. The success of negotiations with Serbia hang on the status of Kosovo, which five Member States have still not acknowledged. Negotiations started with Montenegro in 2012. Regarding Turkey, only three chapters have been opened since the launch of negotiations (in 2005) and 8 chapters have been removed from the negotiations due to Turkey's refusal to implement the Ankara protocol[20]. Macedonia (FYRM) enjoys a recommendation on the part of the Commission that supports the opening of membership negotiations but the disagreement with Greece over its name has prevented the effective launch of these. In 2012 the Commission recommended that Albania be given candidate status, a proposal that was rejected by the Council in December 2013. Bosnia-Herzegovina has made little progress, since ethnic rivalry and the fragmentation of political structures are preventing a shared vision of the country's future.

Since 2004 the EU has offered the countries on its borders a Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), focused on political dialogue and a strengthening of economic ties with the Union, which is now the leading trade partner of most of its neighbours. Refused by Russia, the European offer became a reality via the Union for the Mediterranean (UpM) in 2008 and then by the Eastern Partnership in 2009 which has led to the negotiation of association agreements.

Originally the Commission saw the neighbourhood policy as an opportunity to create a vast pan-European market that would enjoy the four freedoms of the internal market without any decisions being made about ulterior enlargements. This perspective was not retained by the Member States, but it underlies the initiatives taken. Indeed the deep and comprehensive free trade agreements (DCFTA) which form the heart of the association agreement are not just an asymmetric, progressive reduction of customs duties. They also provide for the adoption of a share of the community acquis by the partners. However this policy should not be seen as an extension of the enlargement policy. On the one hand the partner countries have development levels below those in the countries of Central Europe; they face situations in which the rule of law is failing and conflict, both internal and on their borders (except Belarus). On the other hand the Union is of course making an ambitious offer (in a 1000 page document the association agreement with Ukraine plans for the adoption of a number of directives) but which is void of any explicit perspectives of membership but accompanied by an aid package (12 billion € for the period 2007-2013) comparable to that provided by the pre-membership fund. It remains that this offer, together with mobility partnerships, will enlarge the perimeter of a share of the internal market as soon as the neighbouring countries adopt the necessary support policies.

In September 2013 Armenia relinquished the signature of this agreement after Russian pressure threatened its security in the context of the conflict which opposes it against Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh. At the end of November 2013 Ukraine declined the European offer, which led to major, violently repressed demonstrations. Following the departure of Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine did then sign the political agreement on 21st March 2014. On 16th March Crimea solicited its annexation to Russia, which endorsed this in breach of international law. After Moldova and Georgia Ukraine became the third country to lose control of a share of its territory under the impetus of Moscow-backed irredentists.

Short term the consequences of Crimea's annexation to Russia, endorsed by the Duma, are not void of significance: Romania again shares a border with Russia, Member States' cohesion is being put to the test (since Central Europe hosts at one and the same time the firmest and most indulgent elements towards Russia) and the Russian initiative makes it impossible for Ukraine to join NATO. The Russian decision may also revive debate over the intangible nature of Europe's borders, a theme that was temporarily masked since the wars in former Yugoslavia, but ever present in the debate in some Central European countries. From a long term point of view Russia's decision to challenge the territorial integrity of its neighbours who want to escape its influence, could be damaging to it in the end. On the one hand this decision accredits the idea that the geopolitical danger remains in Russia, whilst the country was the second most popular place for foreign investments in 2013. On the other hand it encourages the countries targeted by Russian pressure to diversify their energy supplies and to seek guarantees of security, notably in Poland where the USA's image has suffered over the last few years due to Washington's refusal to do away with visa obligations[21].

In the end the territorial gains made in terms of Vladimir Putin's Eurasian project in exaltation of a Grand Russia as a substitute to the long lost Soviet Union, might prove derisory in the long term. It also seems incongruous at a time when increasing activism by China in the former USSR would logically call for a renewed partnership with the EU.

For its part the latter is struggling to define a project that might have the same effect as enlargement on political, economic and social systems without calling into question the economics of the European project. It is offering its neighbours the adoption of the community acquis without them having either the will or the capabilities of the countries of Central Europe and without taking up some elements that are vital to the success of enlargement, for example a timetable, a clear perspective, significant aid. The discrepancy between the particularly ambitious goals of the neighbourhood policy and the means made available to the partner countries may weaken the credibility of the EU's policy, likewise the European aspirations of its neighbours. After a long period devoted to enlargements the Union is also facing a redefinition of its project. This is a theme that successive constitutional reforms have not exhausted even though enlargement has barely slowed European legislative production. The crisis which seemed the threaten the very existence of the single currency for a time finally led to a strengthening of euro zone governance, thereby lending credit to the scenario that the latter was enjoying increasing political autonomy[22]. This would revive fears in some countries in Central Europe that they are being confined to the periphery of Europe and also lead to debate about the ambition each country has in the region for the euro zone and for the European Union[23].

Conclusion

"To understand the nature of Central Europe," wrote Guido Zernatto[24], "we constantly have to bear in mind that any form of human civilisation is always under challenge: the State, the nation, the fundaments of society and the economy." Whilst the 2nd World War had just started the latter wanted all states to be "able to accomplish their national ambitions whilst living in political communities in which points of tension were reduced to a minimum and as part of an economic organisation which, founded on reason, took on board the demands of the present time." The period that opened as of 1989 has led to this wish being granted. The progress accomplished in terms of stability and development from the Baltic to the Adriatic over the last few years has been spectacular and the European framework has made it possible to stave off recurrent dangers in Central Europe. Some major challenges still have to be overcome but a sign that the transition has succeeded, is that they are shared by all of the Member States. Rising to these challenges does not suppose reconciling antagonistic interests but articulating perceptions that have been passed down through history and which are linked to geography. The return of geopolitics is one of these challenges, such that the change initiated by Moscow will not be completed unless we have clarification of the model Russia intends to follow. A challenge that Vaclav Havel summarised thus: "Russia does not really know where it starts and ends. The day we agree calmly where the EU ends and the Russian Federation begins - half of the tension between the two will dissipate."[25]

[1] This paper focuses on Central Europe and as a result does not take either Malta or Cyprus into account.

[2] David Miliband, British Foreign Minister, An EU " Fit for Purpose in the Global Age ", conference at the London School of Economics, 9 March 2009.

[3] Nouriel Roubini, "Will The Economic Crisis Split East And West In Europe?", Forbes, 26.02.09.

[4] G. Medve-Ba´lint, "The Role of the EU in Shaping FDI Flows to East Central Europe". Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 35–51, 2014.

[5] Edition 02/2014, http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/score/index_fr.htm

[6] Zagorski, Andrei (ed.) : Russia and East Central Europe After the Cold War: A Fundamentally Transformed Relationship, Moscow, 2013.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The expression literally means 'going abroad'.

[9] G. Lepesant, "Pologne : vers un nouveau mode`le de de´veloppement e´conomique et territorial ?", Questions internationales, La Documentation française, Paris, 2013.

[10] Poland's Eurozone Tests, Project Syndicate, 19th February 2014.

[11] European Commission, The 2012 Ageing Report Economic and budgetary projections for the 27 EU Member States (2010-2060), European Economy, 2|2012.

[12] Martin Wolf, "Why the Baltic states are no model", Financial Times, 30.04.2013

[13] The European Commission's recriminations against Hungary were laid out in April 2013 by Commissioner Viviane Reding : http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-13-324_en.htm?locale=en.

[14] Corruption Perception Index 2013, Transparency International.

[15] "L'économie française : comptes et dossiers", Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (Insee), 2007.

[16] These figures refer to the Worker Registration Scheme (WRS). Estimates vary due to the significant number of people from Central Europe already settled in the UK and who said they supported the official opening of the British labour market..

[17] Se´bastien Richard, The Management of Posted Workers in the European Union, European Issue, n°300, 27 January 2014, Robert Schuman Foundation.

[18] Directive 96/71/CE European Parliament and the Council 16th December 1996 concerning posted workers as part of service supply (JO L 18 du 21.1.1997).

[19] Source : Eurobarometer.

[20] Signed in 2005 by the EU and Turkey the Ankara Protocol aimed to complete the EU/Turkey Association Agreement of 1963 (Ankara Agreement) notably in order to open the trade borders between Turkey and Cyprus. Turkey decided however to bind the signature of this agreement with a unilateral declaration maintaining that it did not acknowledge the state of Cyprus. Deeming that in these conditions the Ankara Protocol was not being implemented the EU decided to freeze negotiations relative to 8 chapters on the free movement of merchandise.

[21] During the Ukraine's loss of control over Crimea, 72% of those interviewed in Poland said they feared for the security of their country. In: CBOS news, 09/2014, Warsaw.

[22] German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaüble said in January 2014 that he supported a European Parliament that was limited to the euro zone countries. http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/01/27/germany-eurozone-parliamentidUSL5N0L13KX20140127

[23] F. Bafoil, Europe centrale et orientale, Mondialisation, européanisation et changement social, esses de Sciences Po, Paris, 2006; L. Macek, L'élargissement met-il en péril le projet européen ? La Documentation française, Paris, 2011; M. Foucher, La République européenne, entre histoires et géographies, Belin, Paris, 1999.

[24] G. Zernatto, "L'Autriche et l'Europe centrale", Politique étrangère, 5 (1),1940

[25]Le Monde, 23.02.2005.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Strategy, Security and Defence

Didier Piaton

—

10 June 2025

Two-Tiered Europe

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

3 June 2025

Future and outlook

Stefan Seidendorf

—

27 May 2025

Future and outlook

Thibaud Harrois

—

20 May 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :