Economic and Monetary Union

Philippe Maystadt

-

Available versions :

EN

Philippe Maystadt

The department of Economic Studies at the European Investment Bank has just published a book on investment in Europe and how to finance the economy. This work is a mine of information and this paper aims to highlight the main findings[1], as well as to identify future paths in order to revive investment in and the financing of the European economy.[2]

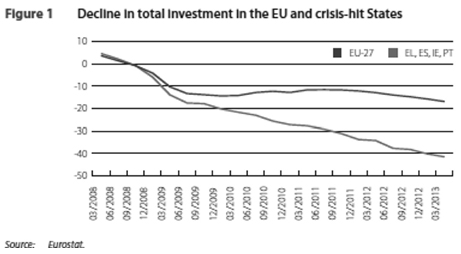

The European Union faces an investment crisis

The EIB's analysis firstly shows that the European Union is facing a severe investment crisis and that this might have serious impact on both its economic and social future. The most recent data shows a contraction in fixed capital investment. The most recent data shows such a sharp contraction in fixed capital that six years after the start of the finan‑ cial crisis and the ensuing recession investment level is still 16.9% lower than in 2007. It is not rising again and in the countries most affected by the crisis it is still falling[3].

(*) en % des votants

(*) en % des votants

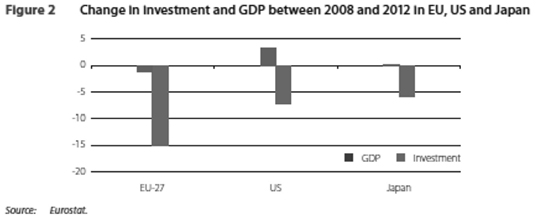

The decline in investment in Europe has been twice that in Europe than in the US and Japan. It was clearly sharper than the GDP contraction from 2008 to 2012, thereby ending the traditional relationship between investment and economic activity. During this period in the EU (15) investment in percentage of the GDP lay on average at 7% lower than the average of the 15 previous years[4].

(*) en % des votants

(*) en % des votants

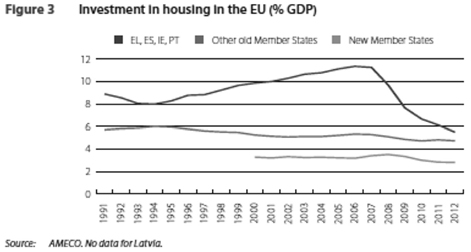

In the main this decline in investment is the consequence of previous imbalances, of over investment in sectors that could not form a sound base for sustainable growth. In the years preceding the crisis some countries experienced an unsustainable expansion of their debt to finance consumption and also excessive real estate investments. Over investment in housing has been the main cause of difficulty in some countries, especially in Spain and Ireland.

(*) en % des votants

(*) en % des votants

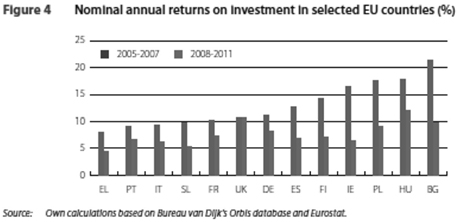

But this evidently does not explain the collapse of in investment in other sectors, notably in infrastructure, equipment and R&D. Amongst the factors discouraging investment we might quote:

– The reduction in the rate of return which has been greater in some countries than in others.

(*) en % des votants

(*) en % des votants

– Uncertainty about the development of the world economic crisis, the solution of the sovereign and banking crises in the euro zone, the economic policy of several govern‑ ments. These are probably been the main reasons why investment has not recovered[5]. It is also why it is so important to complete banking union according to the three stages announced by the European Council in December 2012.

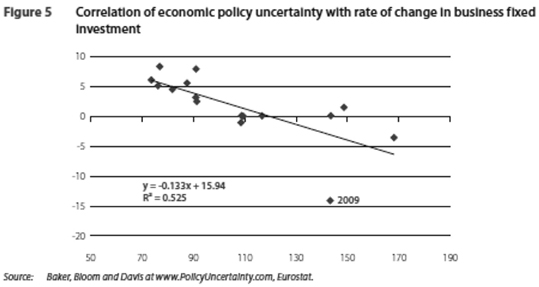

This graph shows the negative correlation between the uncertainty indicator regarding the economic policy and the annual variation in fixed investment by businesses in the European Union (27) for the period 1997‑2012. The uncertainty indicator is that established by Baker, Bloom and Davis[6]. For each 10 point increase in the indicator business investment growth has contracted by around 1.3%. The most notable exception in this period was in 2009 when the dramatic decrease in business investment was caused by the severity of the recession and is not explained by uncertainty about economic policy.

– The drastic decrease in cross‑border capital flows within the European Union, which made countries much more dependent on domestic savings alone and in some cases reduced the offer of financing to an insufficient level.

(*) en % des votants

(*) en % des votants

These causes mainly explain low investment in Europe. Should we add a restriction in the credit supply resulting from the new regulatory framework? In order to avoid having to call on emergency public funds again to save banks, prudential rules were strengthened to make the latter more resistant in the future, notably by reducing the leverage effect. Private bankers announced that the new capital and liquidity require‑ ments would lead to credit restrictions since the reduction of the leverage effect could only be undertaken by a reduction in assets, since increasing capital would be too costly. In other words because they could not increase the numerator enough (own funds), there was no other choice but to reduce the denominator (risk adjusted assets).

This is indeed what happened. The banks fell in line with the new rules, faster than anticipated due to competition, mainly reducing their risk‑adjusted assets. Whilst bank balances increased on average by 18% from 2007 to 2011, loans to businesses and house‑holds only accounted for 5% of this increase; 95% of the increase in assets was invested in other more liquid assets that were deemed less risky, thereby consuming less capital[7]. This has notably been case with public debt securities. Hence according to a study by the agency Fitch[8], the 16 biggest European banks increased their exposure in terms of sovereign debts by 26% or 550 billion in 2011 and 2012. At the same time they reduced their exposure in terms of businesses by 9% or 44 billion. In this study it seems that the average regulatory capital burden on businesses is 4.7% ie 10 times the average on sovereign debts (0.4%).

Most banks have a capital ratio that is comfortably above the minimum demanded by Basel III. According to the European Banking Authority the average CoreTier I ratio of the 61 biggest banks was 10.7% in June 2012, therefore well over the 7% demanded by Basel III. Europe's major banks seem to have plenty of capital and should therefore end their credit restrictions.

However - and this is a factor of uncertainty - some fear that the banks' absorp‑ tion capability to be weaker that in fact it seems because of losses that still have not been included in their credit portfolio. Some observers say that the need to reduce the leverage effect would in fact be greater than revealed by present capital ratios - and this is supposed to be due to loans that may finally prove to be non‑performing[9]. The ECB's Vice‑President, Victor Constancio, who is responsible for the in‑depth analysis of the asset quality of the 128 biggest banks before transfer over to single supervision, suggests that the European banks' situation might be better than suggested by market perceptions[10].

In any event, the impact of the new prudential rules varies greatly from one country to another and from one sector to another. In some countries in the south of Europe the reduction of the leverage effect has probably affected investment negatively. In other countries where the reduction of the leverage effect was still particularly strong, as in central Europe, there has been no perceptible negative impact on investment. However there has been a constant across Europe as a whole: the big companies which can call on the capital market and which are therefore less dependent on bank financing have reduced their investments less on average than SME's. This tends to prove that the new prudential rules have impacted SME investments negatively.

To conclude it has not been established that the new regulatory framework has had a widespread negative impact on investment but that it has contributed to increasing financing difficulties in certain sectors. Apart from SMEs it seems that investment has slowed in innovation because of an inherent risk and in infrastructures due to its long term dimension.

What should be done?

Financing SME's

SME's are more dependent on bank financing than major companies because their access to alternative forms of financing is more limited. At the same time, for the banks the problem of asymmetrical information is more important.

To these well‑known structural difficulties which pre‑date the financial crisis the latter has come as an additional constraint. The additional liquidity provided by banks via the LTRO programme has only been used in part to finance SMEs whilst however this was the justification behind the programme. Regular surveys by the ECB show that the credit terms placed on SME's are becoming increasingly restrictive and in some countries SME access to credit is a major problem.

From the point of view of the commercial banks it is understandable for them to adopt a more selective approach in order to protect the quality of the assets in their balance. But generally restrictions seem greater regarding SMEs. To illustrate this we might mention two examples. In the second half of 2012 SMEs paid 160 base points more on average than the larger companies, but this average covers major differences between countries. The additional price paid by SME's totalled 50 base points in Austria and Belgium, but 174 in Ireland and 261 in Spain. The second fact is the greater number of credit request rejections against SMEs as seen regularly in the ECB's surveys[11].

Hence the need to take steps, either to encourage banks to lend more to SMEs (granting of guarantees which replace the collateral demanded of SME; securitisation of SME credit portfolio in order to free up regulatory capital and to give banks greater lending capacity to SMEs), or to provide SMEs with alternative financing formulae (micro‑finance; private equity). Several authorities have already stepped up their support in this respect either by extending and easing their grant guarantee system on loans to SMEs (notably in France via the BPI), or by supporting micro‑finance institutions (notably via the Euro‑ pean PROGRESS programme), or by providing risk‑capital via specialised institutions, (notably the European Investment Fund, a subsidiary of the EIB). In spite of unfavour‑ able economic conditions microcredit grants have increased in comparison with 2007. As for the capital‑risk market, this collapsed in 2008‑2009, then recovered slightly in 2010‑2011, declined again in 2012, especially in the "early stage" segment. It should be noted that in 2012, public agencies provided nearly 40% of the venture capital invested in SMEs, whilst this share only totalled 15% in 2007[12]. This tends to show that in the present economic circumstances state support is still necessary even though the long term goal should be to establish a liquid capital‑risk market to attract a wider range of private investors.

One recent initiative deserves to be highlighted: the adoption by the European Par‑ liament and the Council of two regulations that have been in force since 22nd July last: regulation No.345/2013 relative to the European capital‑risk funds and regulation No.346/2013 relative to the European Social Entrepreneurship Funds.

In both cases the idea is to establish a common framework to prevent these funds' activi‑ ties from being subject to different rules from one Member State to another and for different qualitative requirements forming inequalities in terms of investor protection and creating uncertainty over the issue of what an investment in one of these funds covers. These funds therefore introduce uniform rules, notably regarding eligible investments, investors who are likely to be called upon, the relationship between managers and investors, the obligation to have adequate own funds and adapted human resources, the settlement of conflicts of interest, the asset assessment method, the obligation to provide regular information about investment policy and targets. The competent authority in the original State checks the respect of these uniform requirements planned for in the regulation on the part of the fund managers and if positive the latter is registered and the authorities in the other Member States are informed of this. From then on, since the fund has a kind of European passport, it can develop its activities in other countries of the European Union.

Another alternative that might be developed is the creation of business networks that enable risk sharing, notably between a major company and a group of SMEs (experiment by Philips subcontracting R&D to SMEs and partially financing them). According to the ECB these BtoB loans are being developed in Germany at present.

Finally there is the idea which is interesting in principle, but in practice difficult to implement; the creation of European an "asset‑backed securities" market in which under‑ lying assets would take the shape of loans to SMEs, prime (and not subprime) loans. Since SME's are typified by their small size and because it is costly for an investor to gather information about them, SMEs only have limited access to institutional investors, even if their credit quality is good. In this context securitisation, if it organised correctly, might be of interest to institutional investors. But it is vital to improve transparency in order to recover investor confidence.

The work undertaken under the impetus of the ECB with the Prime Collateralised Securities (PCS) Initiative deserves to be encouraged. Its advocates have defined common standardisation criteria - quality, simplicity and transparency - so that the depth and the liquidity of this asset‑backed securities market can be guaranteed. The purchase of these ABS's should enable the release of regulatory capital for issuing banks and thereby make it possible to grant further loans to SMEs.

Financing Innovation

Financing innovation is also traditionally subject to certain constraints. This comes firstly from the fact that by nature innovation is an uncertain and risky business. More‑ over innovation projects often include complex information that the banker cannot readily verify. Finally, the effective value of a project only comes to light gradually. This makes it difficult for external investors to appreciate correctly and follow innovation projects effectively. This explains why young innovative companies meet with even greater financing difficulties.

To these structural problems in financing innovation the crisis has brought addi‑ tional difficulties. The uncertainty, which typifies the economic environment, increases the risk inherent to innovative activity, making it even more difficult to finance. The banks which are accused of having taken too many risks have become risk averse; they require greater guarantees which young innovative companies cannot provide. The short‑term approach adopted by many banks because of the new prudential rules also plays against financing innovation, which requires at least mid‑term and often long‑ term commitments. Even capital risk, which is the natural alternative for the financing of innovative businesses has often become too "impatient". Many venture capital funds are now seeking investments that will enable a "rapid" solution - if possible within the next three years - whilst innovation often only produces its value added after 15 to 20 years. Again, state support in "patient" capital seems vital in the present situation[13].

Financing infrastructure

Infrastructure investment requirements over the next decade will be vast, notably because a significant share of existing infrastructures will have to be renewed. The Euro‑ pean Commission has estimated that infrastructure investment requirements will total

1 trillion € up to 2020 across Europe, i.e. the trans‑European transport, energy and telecommunications networks. This estimation does not cover all infrastructure require‑ ments however. For example, infrastructures in the water and waste sectors have not been taken into account, nor have healthcare (hospitals), education, and electricity pro‑ duction investments. If we include these various sectors the most conservative estimates forecast an annual investment requirement of around 650 billion €[14].

At the same time the financial and economic crisis has added further constraint to the financing of infrastructures. On the one hand the States which are forced to undertake "budgetary consolidation" are tending to reduce public investment budgets; electorally it is cheaper to delay investments than to reduce benefits. On the other hand long term financing has become rare, considered to be riskier since it consumes more capital. Finally bond financing has dried up in the wake of the bankruptcy of monoline insur‑ ance companies.

Hence the idea to turn towards institutional investors. At present around 1% of the assets held by pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign funds is allocated to infrastructure[15]. If they accepted to increase this share to 5% over a ten year period (which is a strong hypothesis!), at the end of this period they would have 60 billion € extra investment in infrastructure; in other words not even 10% of the estimated annual requirements. In this optimistic hypothesis institutional investors could therefore make a significant contribution without it being a cure‑all however.

For their part public development banks might help to attract private funds by offering financial instruments based on the sharing or guarantee of certain risks. This is the basic idea behind the project bonds - not to be confused with Eurobonds. A company respon‑ sible for completing an infrastructure project would emit bonds to finance it. For these bonds to reach a ratings level which would enable institutional investors subscription to them, a subordinate tranche would be taken jointly by the European Commission (whose first loss risk would be capped from the start) and by the EIB (which would take on the residual risk). This formula which the Commission has offered for public consultation was received positively by the institutional investors, provided that the new Solvency II prudential rules did not discourage this type of long term investment. Their warning, it seems, has been heeded. On the initiative of Michel Barnier, the entry into force of Solvency II, initially planned for January 1st 2014 has been postponed until January 1st 2016 and the directive will be modified by way of a legislative package entitled "Omnibus II" which the representatives of the Council and the European Parliament agreed to on 14th November last. This modification introduces measures that limit excess market volatility so that insurance companies would be able to continue investing in long term projects. According to Burkhard Balz, the project's rapporteur at the European Parliament, these measures are "totally justified since insurers hold their products until maturity[16]."

More widely the IFRS international accounting standards seem to be causing a problem for long term investors. This was the opinion of the EIB, the German KfW, the French CDC and the Italian CDP in a memo communicated to the EFRAG in March last. This document pinpoints a certain number of problems that the IFRS standard 9 sets for these institutions (the standard addressing the accounting of financial instruments) and indicates that they believe them to be obstacles to long term investment. The present standard does not grant enough importance to the criteria of holding until maturity which is the basis of long term investors' "business model". This leads to undue vola‑ tility in their results which is not representative of their activity and does not therefore provide a true, fair view of their financial position.

Without going into technical details we should simply recall that the classification of financial instruments according to IFRS 9 is based on two criteria: "the business model" and "Contractual Cash Flow Characteristics". Generally speaking the "business model" is a good criteria with which to distinguish between what can be accounted for in terms of amortised cost and in terms of fair value. Unfortunately as this criterion goes together and to a certain extent, is "dominated" by the second, some instruments end up in the wrong category. In short the four institutions insist on giving greater weight to the first criteria and to this effect are drawing up some technical suggestions. Moreover they are asking for the rules governing "hedge accounting" to acknowledge the fact that in a long term business model derivative products can be retained until the full collection of the contractual cash flows.

It has to be admitted that to date the IASB has barely taken this problem on board. But it is possible that the discussion which the IASB, encouraged by the Europeans, has just started over the revision of the IFRS's conceptual framework[17] will enable a review of the vital issue of the business model and finally achieve its consideration when it comes to establishing or revising certain accounting standards.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

Strategy, Security and Defence

Jean Mafart

—

27 January 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Iana Dreyer

—

20 January 2026

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Earl Wang

—

13 January 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :