supplement

Julien Zalc

-

Available versions :

EN

Julien Zalc

15th September 2013 is a sad anniversary: five years ago on 15th September 2008 the bankruptcy of the merchant bank Lehman Brothers heralded the start of the greatest period of economic turbulence since 1929. There have been five years of financial crisis, of economic and monetary crisis, followed by the public debt crisis which has now become a social crisis, with unemployment affecting more than a quarter of the population in some EU Member States. Five years? It is more than that in fact: the crisis started in the summer of 2007 with the subprime scandal in the USA, whose turmoil was felt on this side of the Atlantic. In this time European public opinion has been severely shaken and economic indicators and support for the European Union have fallen sharply, sometimes reaching record lows in the history of the Eurobarometer.

Where are we now? Can we at last foresee an end to the crisis for the European Union? Some economic indicators seem to be rising above the green line again. In the spring of 2013 the European Commission published some quite encouraging economic forecasts for 2014[1]: they are forecasting a return to positive growth in 2014, even though the outlook remains gloomy for the rest of this year. Moreover there are favourable signs from the USA where there is now talk of economic recovery. There has also been a change in tone in some official discourse, notably in France: François Hollande feels that "something is happening in the economy", Pierre Moscovici believes that "2014 will be the first year of true growth", and Christine Lagarde declares she is "desperately optimistic" for world growth. So is self-persuasion being used to make consumers confident again in order to revive consumption? Or are there real signs that Europe is beginning to emerge from the crisis?

One indicator is still a source of concern however: unemployment is constantly rising, notably in the euro zone. In the first quarter of 2013 the unemployment rate lay at 11% in the European Union and at 12.2% in the euro zone. The question of employment is high in the minds of the Europeans and it affects all survey results.

In spite of the extreme concern about unemployment the results of the most recent Eurobarometer surveys seem to show that in terms of European public opinion "something is now happening." In the last Eurobarometer Standard of spring 2013 we note a real improvement in forecasts for the future. At the same time concern about economic issues is declining (except for unemployment), whilst concern about social and societal issues seems to be gathering pace. The combination of these different elements shows perhaps that European public opinion is starting to recover for the duration.

However one question remains: the differences between Member States and between various socio-demographic categories have grown. The most significant gaps have been recorded in the wealthiest countries and amongst the wealthiest categories of the European population; they are not as big within the most vulnerable categories. This is the flipside of the coin. The improvement in the economic situation seems to be moving alongside an increase in inequalities.

Finally another more political event has to be taken on board: the prospect of the European elections in May 2014 when nearly 400 million citizens will be called to ballot to elect their MEPs. For the first time they will be taking indirect part - via their vote - in the election of the next President of the European Commission. An insignificant detail? Not at all. It might be a real opportunity for the European Union.

1/ GREATER EXPECTATIONS FOR THE FUTURE

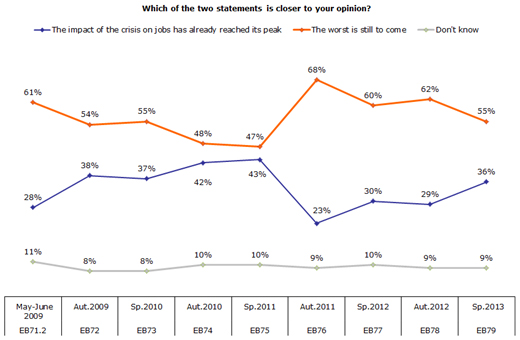

Several Eurobarometer questions focus on European citizens' forecasts for the future. Hence they were asked about their expectations for the next twelve months regarding the national, European and international situation. But they were also asked about how they felt about the impact of the crisis on employment. Had this peaked or on the contrary was the worst still to come? In the most recent Eurobarometer Standard (EB79, spring 2013), these projective indicators showed significant progress.

This is notably the case with short term forecasts about the economic situation. Of course the share of optimists still forms the minority. Less than one European in five only thinks that the next twelve months will be "better" in terms of the national, European or world economic situation (18% for the three levels tested)[2]. These shares have been quite stable since the previous survey undertaken in the autumn of 2012[3]. But pessimism is quite clearly receding: six points less in terms of the national economic situation (34% for "not as good"), seven points less for the European situation (32%) and six points less concerning the world economic situation (27%). The category "no change" has risen in the three instances (national level +5; European +4; world +4). From a national and European point of view there are now less pessimists than citizens who are forecasting a status quo.

At this stage we cannot yet speak of a real turn-around and a real recovery in confidence; this is all the more true since for the time being the decline in pessimism is not occurring to the benefit of optimism which only shows moderate increases (+1 ; +2 ; +1 respectively). But it is possible that the rise in the indicator "no change" is just an intermediary stage, a first step towards a real improvement in the European state of mind and their forecasts for the future. It seems that the "ex-pessimists" first choose the answer "no change" before they move quite firmly into a phase of optimism.

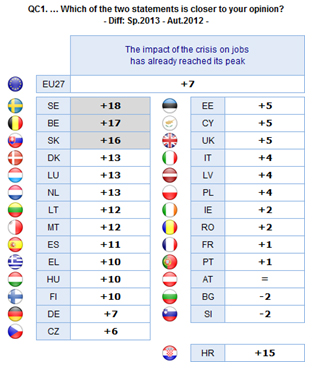

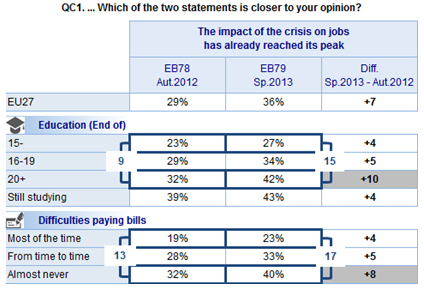

Another –also projective - indicator confirms this improvement in the state of the opinion. The feeling that the effects of the crisis on employment have reached their peak is rising quite clearly (+7 points in comparison with autumn 2012, to 36%[4]), whilst the opposite opinion is declining (55%, -7).

European expectations for the near future are much better than in autumn 2012. But the indicators studied are often subject to major developments from one study to another. Do we have the elements that might lead us to believe that this improvement is here to stay?

2. APART FROM UNEMPLOYMENT ECONOMIC CONCERNS ARE DECLINING WHILST SOCIAL AND SOCIETAL ISSUES ARE RISING

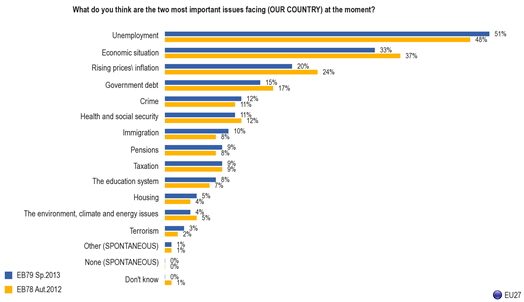

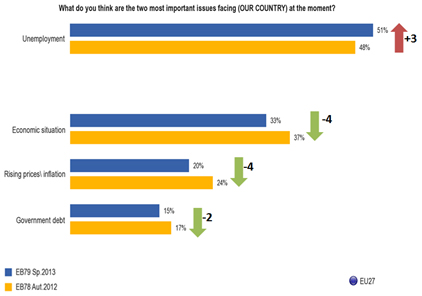

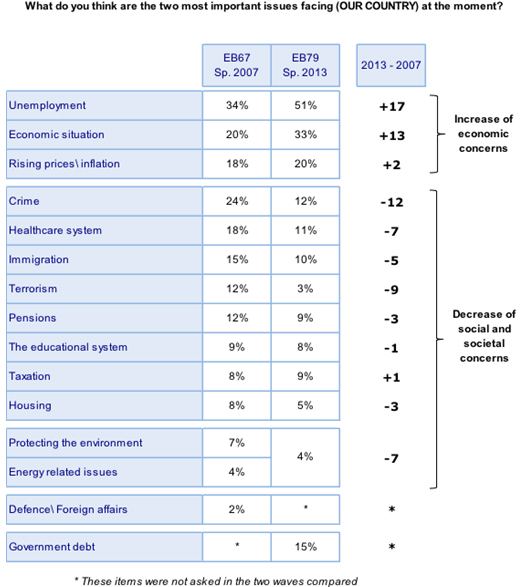

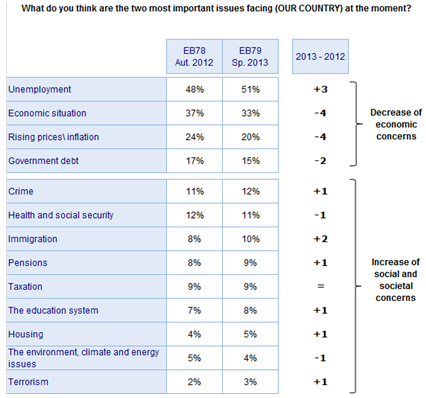

Europeans believe that unemployment is by far the main problem that their country is facing. More than half of them answer this (51%), far ahead of the economic situation (33%), inflation (20%) and the public debt (15%)[5].

Hence these four economic questions dominate European concern. But an analysis of developments reveals that although unemployment is still rising (+3 points since autumn 2012), this is not the case in other economic dimensions which are declining: this is the case with the economic situation (-4), price/inflation rises (-4), and with the public debt (-2). It is a general trend: although the preoccupation regarding unemployment continues to increase, generally economic issues are losing ground.

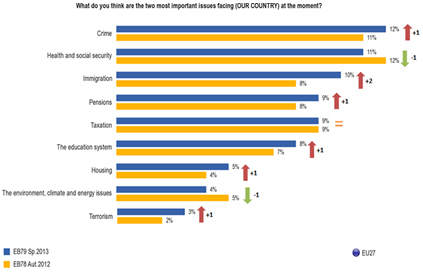

The decline in concern about economic issues is occurring in part to the benefit of unemployment but other issues of concern are also on the rise: this is the case with crime (+1), immigration (+2), retirement (+1), the education system (+1), and housing (+1).

Taken individually these increases are limited but we should note however that the general trend is upwards as far as social and societal issues are concerned.

This shift in concern from the economic to the social sphere is significant: although in periods of crisis, economic issues mainly prevail, social and societal issues are clearly more significant in periods of (relative) economic prosperity, as for example before the summer of 2007. Let us look back: what were the main national concerns of Europeans in the spring of 2007?[6] : the first three positions were dominated by unemployment (34%), crime (24%) and the economic situation (20%), ahead of price rises (18%), the healthcare system (18%), and immigration (15%). Terrorism and pensions were quoted by 12% of the Europeans, ahead of the education system (9%), taxes (8%) and housing (8%).

Social and societal issues were therefore all spoken of more than at present with differences ranging from up to 7 points and even 12 (in terms of crime[7]. In times when concern about the economy is not as strong citizens worry more about issues that affect their daily life, like healthcare, crime and housing.

This is the trend we see in the spring survey 2013: social and societal dimensions have nearly all risen. For the time they still lie well below economic dimensions but this general trend upwards in terms of social and societal issues may well mean that public opinion feels that that the end of the crisis is gradually drawing closer.

3. INCREASING INEQUALITIES

Although we have to resist being overly optimistic, notably because unemployment is still rising, various elements provide us with hope. However these improvements do have a negative aspect. Inequalities are growing between Europeans.

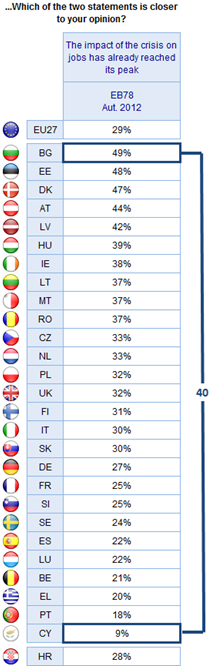

The analysis of national developments around the question concerning the impact of the crisis on employment reveals that even though sharp increases have been seen in Belgium (+17)[8] in Slovakia (+16), the most striking of these have especially affected the EU's wealthiest countries: this is notably the case in Sweden (+18), Denmark (+13), Luxembourg (+13) and the Netherlands (+13). In Cyprus (+5), Italy (+4), Ireland (+2) and Portugal (+1), - which have been more severely affected by the crisis - these increases have not been as sharp[9].

Whilst in the autumn survey 2012, 40 points separated Bulgaria, where there was the strongest feeling that the effects of the crisis on employment had already peaked (49%), from Cyprus, where it was the lowest (9%), there is now a 46 point difference (between Denmark, 60% and Cyprus, 14%).

The same can be seen between socio-demographic categories. In the autumn of 2012 there was a 9 point gap between the least qualified and the most educated (under 15, 23% ; over 20, 32%) ; there was a 13 point gap between those who had difficulties in paying their bills most of the time and those who practically never had this type of problem (most of the time 19% ; almost never, 32%). In the spring of 2013, the gap had grown significantly: there is now a 15 point gap according to education level and a 17 point gap concerning difficulties in paying bills.

When the European average rises it is the wealthiest countries and population categories which are behind these rises. Increases are often slighter amongst the countries which are struggling most and amongst the most vulnerable population categories. It seems then that to the backdrop of improvements in the European situation inequality between Europeans is growing.

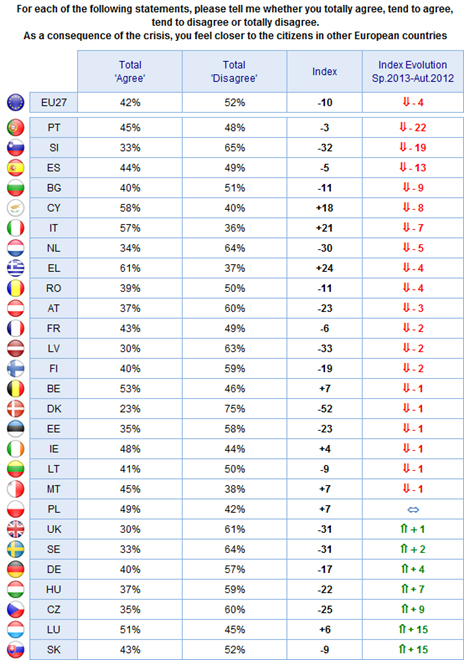

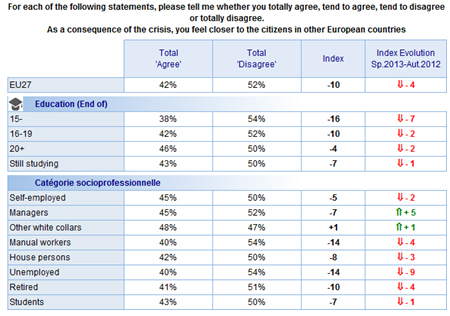

In this context it is not surprising that most Europeans do not feel closer to citizens of other Member States following the crisis (52%, against 42%)[10]. The "agree" indicator[11] has dropped four points since the last survey and - sometimes spectacularly - decreases have been recorded in 18 Member States (-22 in Portugal, -19 in Slovenia, and -13 in Spain).

At the same time this indicator has declined in most socio-demographic categories. Decreases have been a little sharper amongst the unemployed (-9) and those with few qualifications (-7).

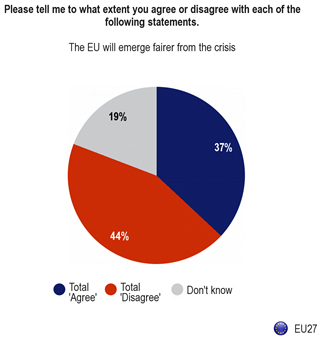

Finally when asked about what the European Union would be like after the crisis Europeans are pessimistic. Most of them believe that post-crisis Europe will be more unjust (44%, against 37%)[12].

The European Union faces a major threat in this. Indeed it has to ensure that all Europeans, in all Member States and all socio-demographic categories benefit from the economic revival (it still seems too early to speak of an end to the crisis). Indeed if inequality between Europeans worsens it is likely that negative attitudes towards Europe will accentuate.

4. THE EUROPEAN ELECTIONS: AN OPPORTUNITY FOR THE EU's FUTURE

In May 2014, Europeans will be called to elect their MEPs. The European elections which until now have been marked by constantly declining turnout[13], might well provide the EU and its institutions with a real opportunity to restore their image amongst public opinion.

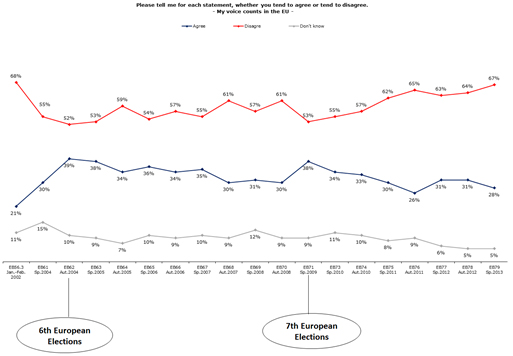

Let us start with one observation: the indicator "my voice counts in the European Union" rose significantly during the last two European elections in 2004 and 2009. In Eurobarometer 62[14], undertaken just a few months after the European elections of June 2004, the indicator rose to 39%, i.e. an increase of 9 points in comparison with the previous survey (undertaken in February-March 2004)[15]. The same applies to the spring 2009 survey , undertaken between 12th June and 8th July, i.e. just after the June 2009 elections: the feeling that (his/her) voice counted in the EU rose by 8 points (to38%) in comparison with autumn 2008[16]. We might then expect a significant increase in this indicator after the May 2014 elections - this is all the more true since it is particularly low (28% of Europeans believe that their voice counts in the EU, the third lowest level ever registered).

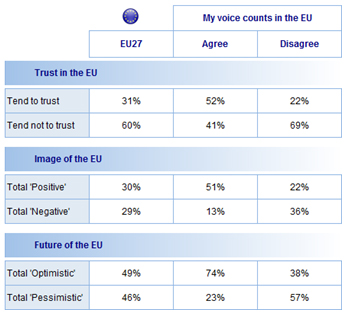

But this variable is strongly linked to support indicators to the Union. An absolute majority of Europeans, who feel that their voice counts in the EU are also confident in it (52%), they have a positive image of it (51%) and are optimistic about its future (74%). Conversely only a minority believe that their vote does not count in the EU (22%, 22% and 38% respectively)[17].

It is highly likely therefore that at the next European election the various support indicators to the European Union will rise. This will be all the more so since the improvement in how people view the economic situations creates a more favourable environment.

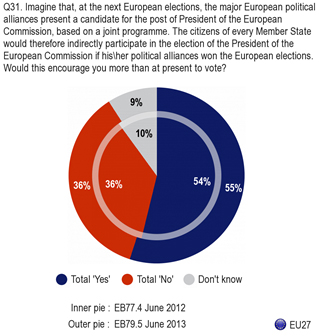

For the first time in the history of the European elections the major political groups are to appoint, prior to the vote, a candidate for the post of President of the European Commission. Citizens from all Member States will therefore be - indirectly - taking part in the election of the President of the Commission in the event of victory by their political group in the election. When asked about this a majority of Europeans supported the idea: an absolute majority even said that this would give them greater encouragement to vote than at present (55% against 36% who believed the contrary)[18].

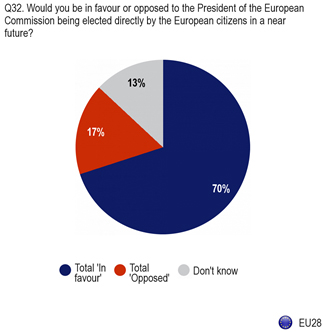

Europeans want to go even further than this and elect the President of the European Parliament directly in the near future: 70% of them say they support this against 17% who are against it.

These elections might lead to a truly positive change in European public opinion about the European Union and its institutions. During this democratic event citizens will feel that they are being considered by the Union and this feeling may even be strengthened by the fact that they are participating, via their vote - in the choice of the future President of the Commission. To do this Europe has to put everything on its side and notably introduce an effective communication strategy to inform the population about this development. It mainly has to highlight the fact their vote will now have immediate effect on the functioning of the institutions. The effect on European citizens' feelings about the European elections and beyond that their institutions is potentially important. For the first time it might also reverse the trend in turnout in the European elections.

Conclusion

The years of crisis experienced by Europe have left their mark: in this time many Eurobarometer indicators have reached their lowest ebb and mistrust of the Union and its institutions has never been as high. But there might be light at the end of the tunnel.

The most recent Eurobarometer surveys reveal information that encourages us to be optimistic - even though this is relative: an improvement in economic forecasts is the first encouraging sign. This is all the more so since it goes hand in hand with a downward trend in economic concerns and a rise in concern about social and society issues. Taken individually these increases are limited but a general trend seems to be emerging.

Why should we be glad that some concerns have replaced others? This is because in periods of relative economic prosperity (as before the crisis in spring 2007), concern focused more on social and societal issues. The combination of these various factors (improvements in forecasts for the future, decline in economic concerns and increased concern about social and societal issues) might indicate that the European Union is gradually moving towards a situation similar to that before the crisis. We might then ask whether the morale of European public opinion isn't moving towards a new more positive cycle.

But this positive development has a flipside: inequality between Europeans seems to be growing. It appears that only the wealthiest are emerging from the crisis and not the entire Union. There is a real danger in this, which the European Union and its institutions must take on board. They have to ensure that if there is recovery it is to the benefit of all. Unless this happens negative opinion and even hostility towards Europe might continue to rise and the European elections will be used as an outlet for those left by the roadside.

This would be a shame since this electoral event is a real opportunity. For the first time ever voters are going to take –indirect- part in choosing the President of the European Commission and this novelty seems to convince a good share of European citizens. They will be more involved in the decision making process, which will bring them closer to the institutions. Apart from this democratic step forward electing the President of the European Commission, the European elections will provide Europe with a face, which too often appears to be a distant, shapeless "nebuleuse". This might have a real effect on the relations Europeans have with the institutions. To do this citizens require information and explanation about this institutional development and what it means. Just months from the election the situation is an urgent one. It is high time to prepare effective communication tools that can be deployed when the electoral campaign starts. There are many issues to think about: which messages should be emphasized? What will the targets be? How should the changes be explained without being too technical? Which arguments should be prepared to counter the critics who will not hesitate to join the eurosceptics? The task is a difficult one and the stumbling blocks many - but "it is worth it": the image of the European Union and its institutions can and must benefit from each European election.

[1] http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/eu/forecasts/2013_spring_forecast_en.htm

[2] Eurobarometer Standard 79, spring 2013 http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb79/eb79_first_en.pdf

[3] Eurobarometer Standard 78, autumn 2012 http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb78/eb78_first_en.pdf

[4] Cf EB Standard 79

[5] Cf EB Standard 79

[6] The crisis started in the summer of 2007 with the subprime crisis in the USA. The survey analysed is EB67 of the spring 2007 http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb67/eb_67_first_fr.pdf

[7] We should note that the list of items is not strictly the same in the two surveys: in 2013 the item 'public debt' has replaced 'defence/foreign policy' ; moreover the items 'protection of the environment' and 'issues linked to energy' have been merged to form one item " environmental, climate and energy issues'. These changes also contribute to the explanation seen since 2007.

[8] Difference EB Standard 79 (spring 2013) - EB Standard 78 (autumn 2012)

[9] Major increases noted in Spain (+11) and Greece (+10) have not helped these countries improve their position (with 33% and 30% respectively for "impact of the crisis on employment has already reached its peak" and which is still below that of the wealthiest countries.

[10] Cf EB Standard 79

[11] Difference between the "totally agree" and "totally disagree".

[12] Cf. EB Standard 79

[13] Reminder of the turnout rates in the various European elections : 1979 : 61,99% ; 1984 : 58,98% ; 1989 : 58,41% ; 1994 : 56,67% ; 1999 : 49,51% ; 2004 : 45,47% ; 2009 : 43,00%

[14] Eurobarometer Standard 62, autumn 2004 http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb62/eb62first_en.pdf

[15] Eurobarometer Standard 61, spring 2004 http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb61/eb_61_first_en.pdf

[16] Eurobarometer Standard 70, autumn 2008 http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb70/eb70_first_en.pdf

[17] Cf. EB Standard 79

[18] Special Eurobarometer: " One year before the European elections 2014", June 2013 http://www.europarl.europa.eu/pdf/eurobarometre/2013/election/synth_finale_en.pdf

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :